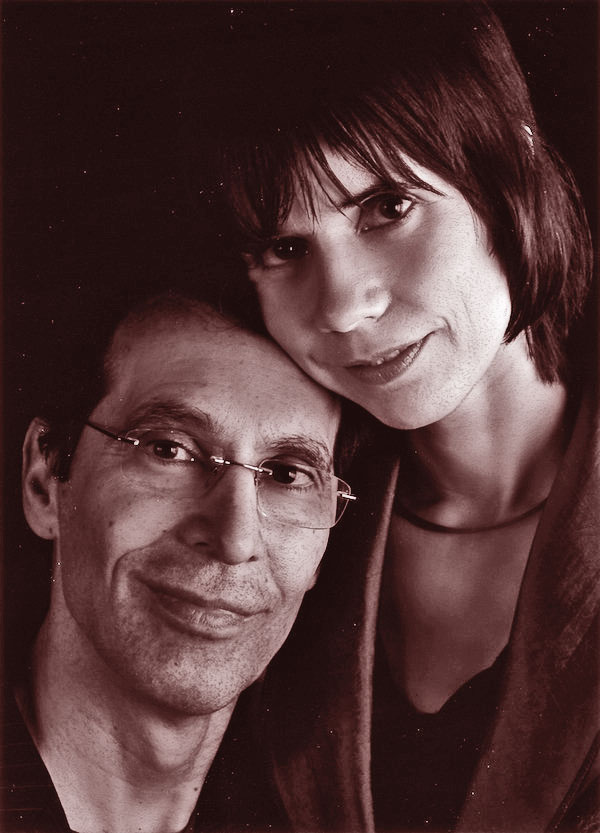

– By Ana Melikian; Collectibles courtesy James S. Melikian Collection –

Jim Melikian was window shopping.

Normally, the 61-year-old Arizona businessman scoured auction catalogs for items he’s been collecting since he was a teen—religious artifacts from around the world, pieces of Latin-American and black history, precious items from the life of Muhammad Ali. He intends to display them one day in a museum he’ll build in Phoenix, sharing with the world a passion that has more than once drained his bank account, but which he says has always been “a joy for me.”

Yet here he was, in June 2016, salivating through 124 pages of the Legends of the West catalog by Heritage Auctions, and a whole new world of possibilities was opening up to him.

“I couldn’t believe it—there were 178 lots, mostly from Tombstone—the most famous thing in Arizona history. Most were from the 1870s and ’80s, from the collection of a guy in Tucson. I thought, ‘What if I get a few pieces for my museum? I’ll get four or five things.’”

A few pieces caught his eye right away: The bank draft cashed on the very day of the shoot-out behind the O.K. Corral; an 1879 petition with the signature of Tombstone founder Ed Schieffelin; the first-known postage stamp from the mining town, dated August 26, 1879.

“I kept saying to myself, ‘This is cool stuff, but is it rare?’” So Melikian turned to two guys he knew would know, Arizona historian Jack August and True West’s Executive Editor Bob Boze Bell. Bell cautioned that Melikian should be sure the items were authentic, but told him, “If it’s real, go for it.” August was even more encouraging, assuring Melikian the items were not only rare, but priceless.

An anonymous Tucson collector was selling the remarkable set of documents that the catalog touted as “one of the finest collections of early Tombstone and Arizona Territory items ever to appear at auction….” August wasn’t surprised to see such items in private hands. He knew that in the early 1900s, towns like Tombstone weren’t particularly careful about their records. “In 1929, the county seat shifted from Tombstone to Bisbee, and a lot of stuff just got thrown away or scattered,” said August, who died at the age of 63 this January.

Melikian was convinced and bid on a couple things. And won. “The hard part is not bidding,” he jokes. “The hard part is paying.”

But he hadn’t spent that much and was pleased that he’d begun a brand new collection. “I had just paid off all my credit cards and had $100,000 in credit, and when you’re a collector…” He holds out both hands in a gesture of “Isn’t it obvious what you do next?”

Then he realized that most of the items in the catalog were still available. So he bought some more. Then some more. And $80,000 later, he had acquired about half the Tombstone collection. “I felt like a picker by the end,” he says. “But for a collector, it’s having something nobody else has.”

Like every collector, having these items fueled his curiosity for others that told the story of the Old West. He became intrigued by a photographer not as famous as C.S. Fly, but just as skilled, Tucson’s Henry Buehman. “I found people who’d bought hundreds of his photographs, and I started buying them too. That was another $20,000.”

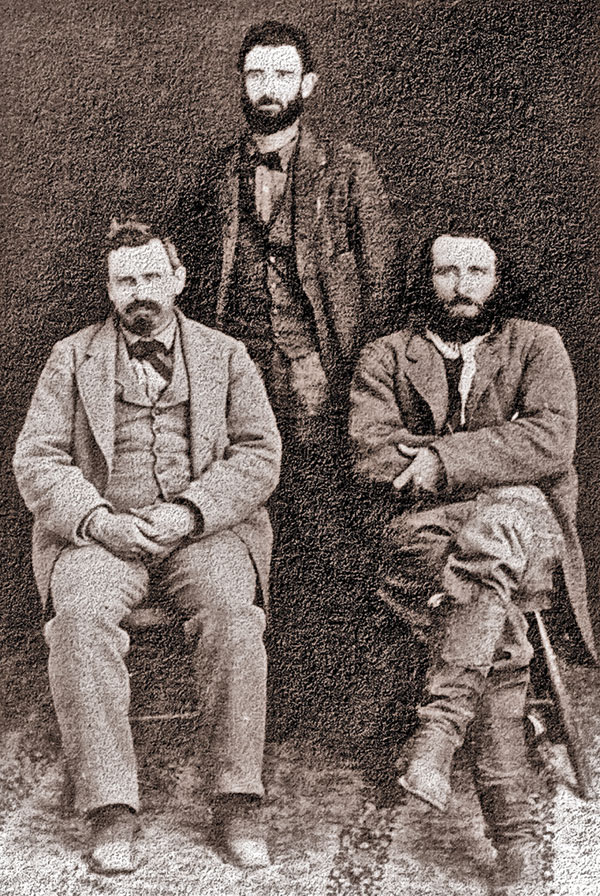

– Schieffelin photo True West Archives –

His museum is still a dream, but Melikian decided his new Tombstone collection needed to be shared immediately. With August’s help, he offered a sampling at the Arizona State Capitol in an exhibit that opened on September 22, 2016—exactly one day after the moment 139 years ago that Schieffelin filed his first mining claim on Goose Flats and named it Tombstone. Melikian not only let the public see these rare documents, but also provided a history lesson about Arizona’s most famous frontier town.

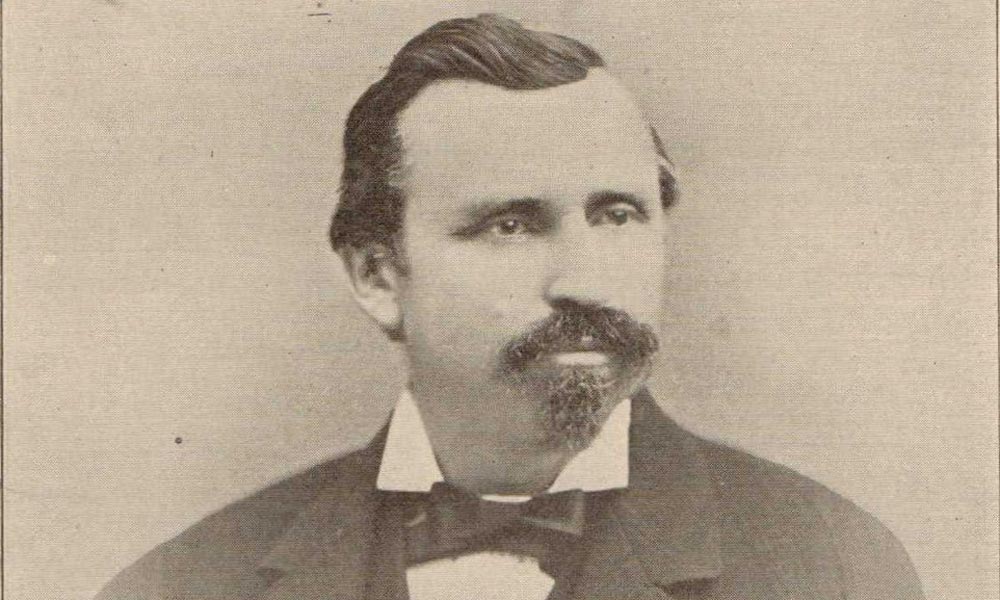

Schieffelin was a 30-year-old U.S. Army scout and prospector when he went searching for his fortune in silver—dissuaded by a friend who warned him, “The only rock you will find out there will be your own tombstone.”

He went looking in a dangerous area, not far from the Cochise Stronghold that had long been a hideout for the Apaches. But Schieffelin had the last laugh, becoming fabulously wealthy from the silver that poured out of the Tombstone area. The boom lasted until the 1890s, producing about $85 million (roughly $2 billion today) in silver.

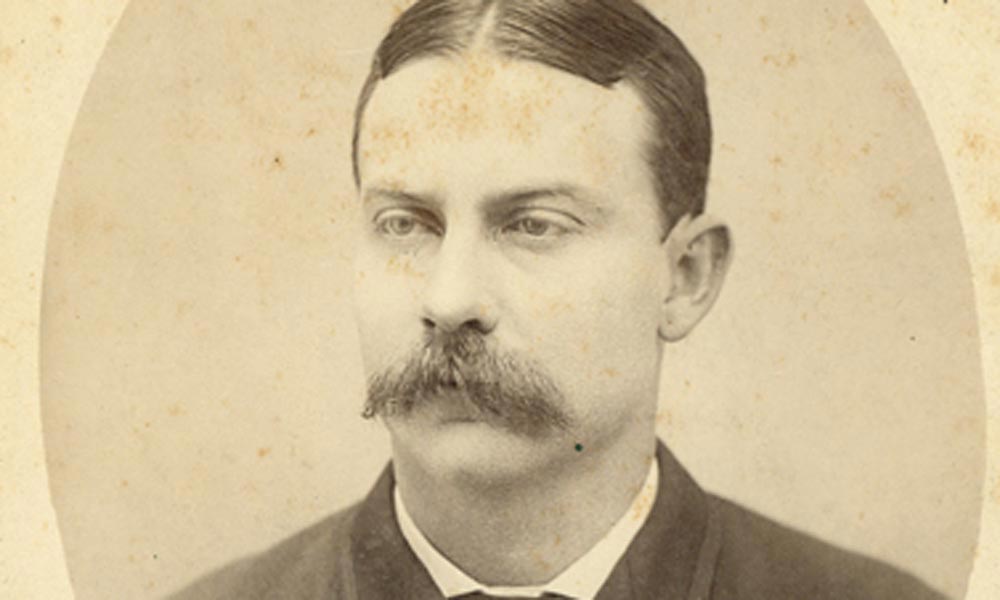

With the riches came the town still known as “Too Tough to Die.” By the mid-1880s, Tombstone was a complete community of churches, banks, newspapers, gambling halls, saloons, brothels, an opera house and a bowling alley. And yes, home to the O.K. Corral on Allen Street that would be forever famous because of Wyatt Earp and John Henry “Doc” Holliday (even though the 27-second gunfight actually took place six doors west of the O.K. Corral’s rear entrance.)

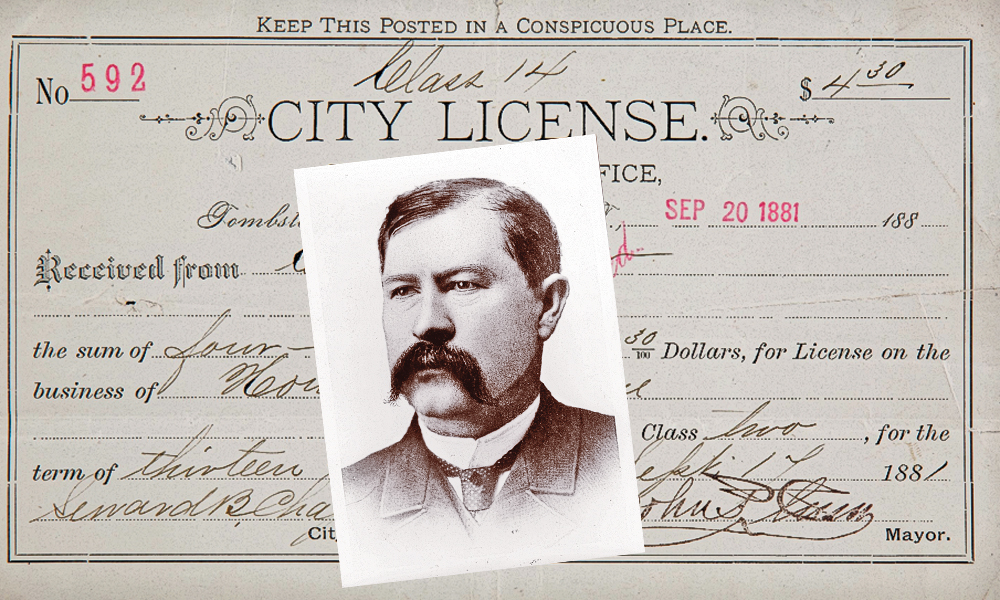

– True West Archives –

Why does the famous gunfight seem more real when an actual document from the very day of the shoot-out lays before you in a glass case? As the auction catalog noted, “Documents from Tombstone bearing this date are quite rare.” The bank draft is from the Pima County Bank, payable to Hawkins, Boarman & Company, wholesale dealers in wines, liquors, oils and cigars. The $250 check is signed by P.W. Smith, the bank manager, and bears the stamp of October 26, 1881.

Even more fascinating is a document with 28 signatures of the “who’s who” of early Tombstone—a four-page petition asking the county board of supervisors to appoint John Brannick as constable. Besides Ed Schieffelin, the document features the signatures of his brother Al; W.A. Harwood, the first mayor of Tombstone; Marshall Williams, Tombstone’s Wells Fargo agent; C.J. Whitehurst, prominent Cochise County cattleman; Carl Gustave “Gus” Bilicke, prominent businessman who built and operated the Cosmopolitan Hotel on Allen Street; D. Waughtal, a relative of Morgan Earp’s wife, Louisa; and Otto Geisenhofer,

who opened the first bakery in Tombstone in 1879.

That petition was filed on October 6, 1879, two months before the Earp party arrived, and included two men who would witness, two years later, the famous shoot-out: gambler Wesley Fuller and land speculator William “Billy” Allen.

Thanks to consummate collector Melikian, these historic Tombstone documents are once again telling their stories to the public.

But he does have one story he hopes won’t get told. “I know I’ve been reckless and irresponsible [spending so much],” he says, “and I just don’t want my wife to read this article.”

Jana Bommersbach has earned recognition as Arizona’s Journalist of the Year and won an Emmy and two Lifetime Achievement Awards. She cowrote the Emmy-winning Outrageous Arizona and has written two true crime books, a children’s book and the historical novel Cattle Kate.