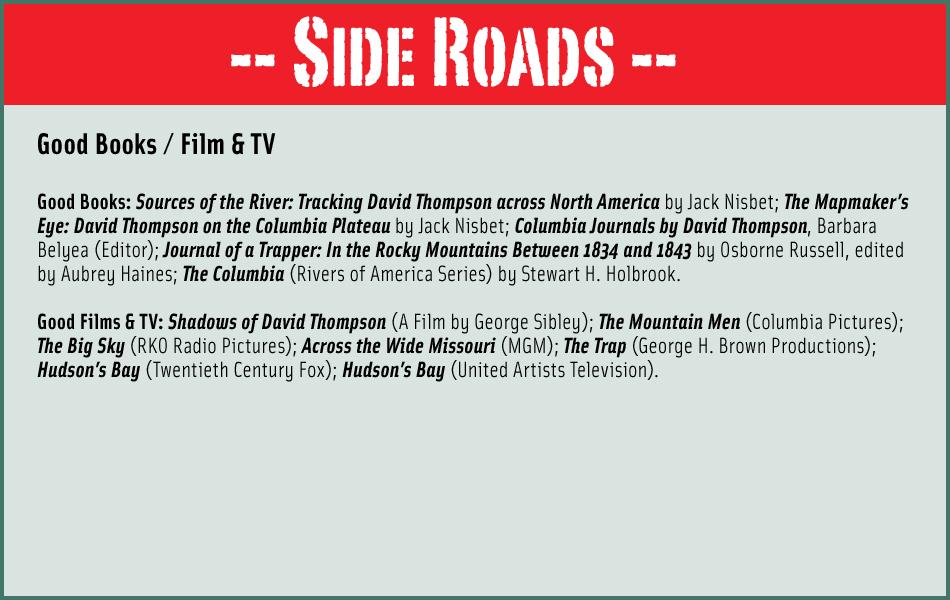

David Thompson was fourteen when he began his life in North America as a clerk’s apprentice with the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC). He may have been in HBC’s employ for decades if he had not had a chance to do a bit of exploring across Canada.

David Thompson was fourteen when he began his life in North America as a clerk’s apprentice with the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC). He may have been in HBC’s employ for decades if he had not had a chance to do a bit of exploring across Canada.

The idea of seeing new country obviously appealed to the boy, who after suffering with a severely broken leg that laid him up in camp for most of a year, learned the skills necessary to survey and map the countryside.

Working for HBC, Thompson visited portions of central Canada, but when it appeared the company intended to assign him to a stationary post, he did not hesitate. He quit HBC and, not even skipping a beat, immediately found a job with the North West Company.

This rival company, also headquartered in Canada, already had trading posts across the province, and soon Thompson picked up his explorations. He was one of the first fur traders to cross the Canadian Rockies from Rocky Mountain House (north of Calgary) into the interior valley of the Columbia River source west of the Continental Divide, and he became the first white explorer to travel the full course of the Columbia River.

Following a Trail Blazer

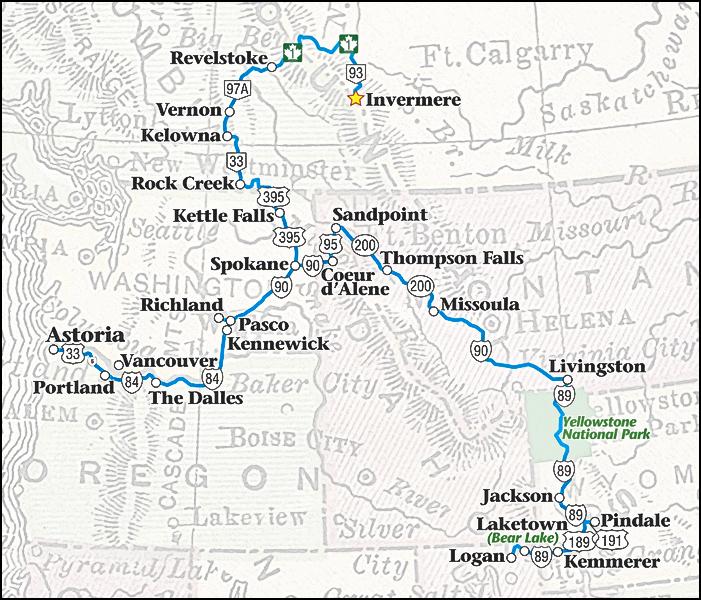

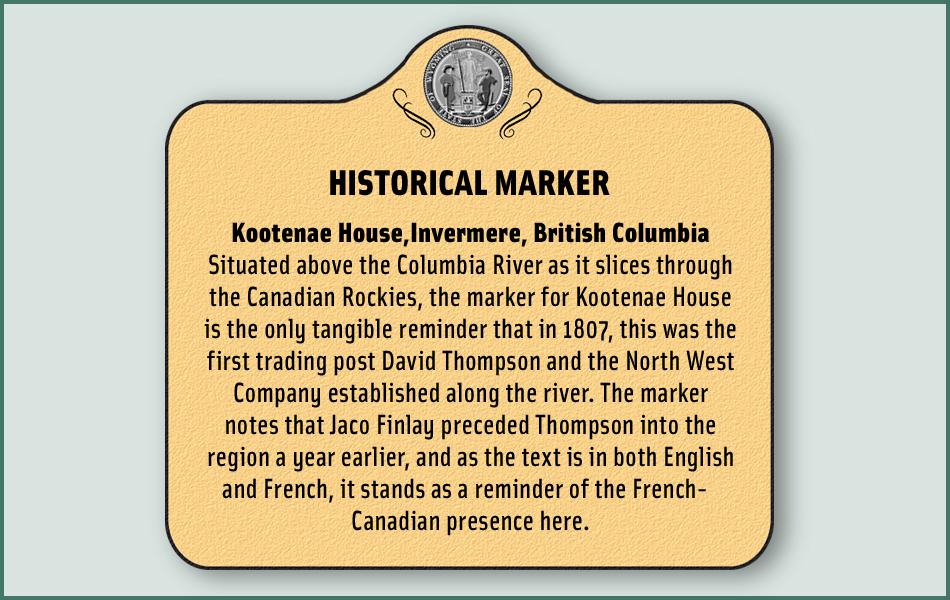

I picked up Thompson’s North West Company (NWC) trail in Invermere, British Columbia, finding a life-size sculpture of Thompson and his Cree wife, Charlotte Small, at a small park near the city’s main business district. A visit to the Invermere Museum and a viewing of its small display related to Thompson and the NWC gave me the information I needed to locate the site of Kootenae House, established in 1807 by Thompson. From this point Thompson traded with native trappers and explored the Kootenay River and the Upper Columbia River. Ultimately he would establish a chain of fur trade posts in northern Idaho, and along the Columbia watershed. Situated on a hillside above the river, Kootenae House remained in use periodically until 1812, when it was abandoned.

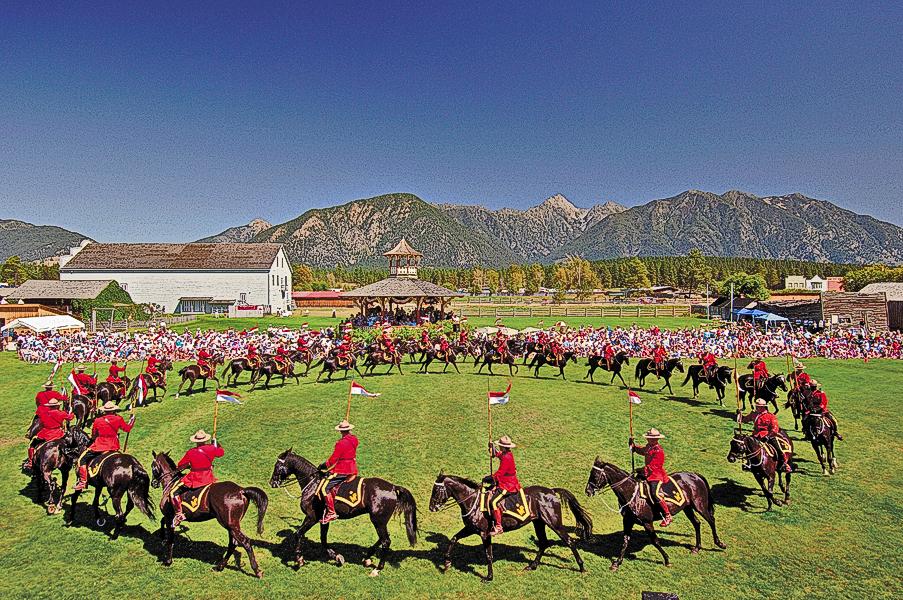

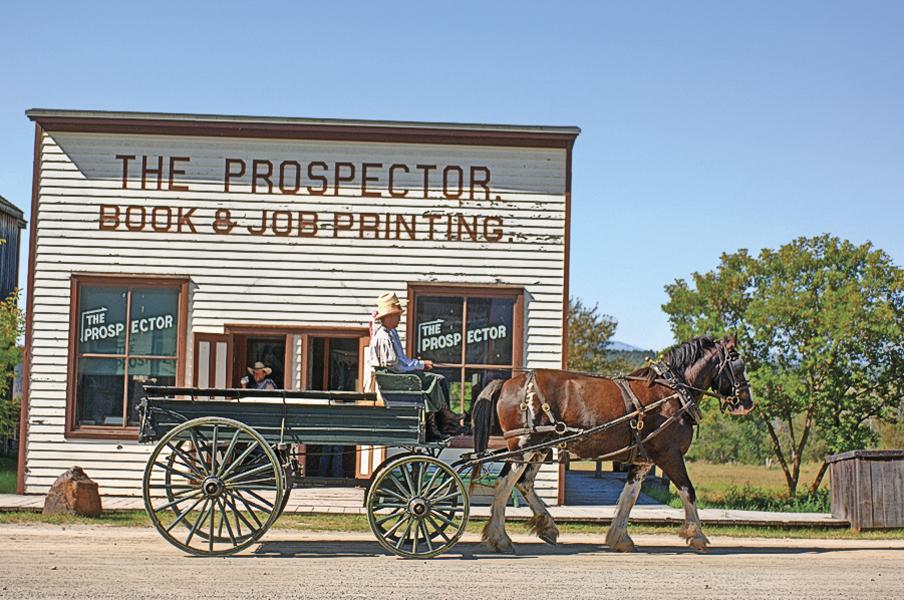

On my route to Invermere, I had made a stop at Fort Steele, now a heritage town, hoping to bump into a living history interpreter I know in the region who portrays Jaco Finlay, the NWC explorer who preceded Thompson into the Columbia drainage in 1806. While I did not find my friend, I did have a great time at this heritage site.

From Invermere I begin following the Columbia River—north! Yes, in this area of Canada the mighty river makes a long route north before it carves through stunning high peaks and begins a swing to the south. My next stop is Revelstoke, a main point on the Canada Pacific Railroad (and home of the Revelstoke Railway Museum). In the evening I take in the music at Grizzly Plaza (styles change nightly and it happened to be blues when I was in town). But honestly I’m more interested in the Revelstoke Museum and Archives, which has a small exhibit about Thompson and the North West Company. After a cup of tea with the museum director (there are perks to my job!) and a review of their exhibits, including one about the various nationalities of people who live in Revelstoke or who have visited here, I’m back on the road.

West of Revelstoke, I cannot resist a stop at the The Last Spike—the point where the Canada Pacific Rails met—the equivalent of Promontory, Utah, where the Union Pacific and Central Pacific met in 1869. And I visit 3 Valley Gap Heritage Ghost Town, where I step into most of the 25 historic structures, and am amazed at the Roundhouse. While

I suspect most of the tour busses unload at the Revelstoke Railway Museum, this Roundhouse exhibit is phenomenal. It may not have fancy interpretive signs, but the fact that you can explore several engines and train cars makes this totally worth the stop.

Following the Columbia Southward

David Thompson and the NWC weren’t content to work the streams in Canada, although they did establish a post near today’s Kamloops, British Columbia. The Columbia rolls south, flowing out of British Columbia into today’s Washington, before it turns west and forms the border between Washington and Oregon. I head south, too, crossing the Canadian-American border north of Kettle Falls, Washington. (A travel note here, the first border crossing point I reached closed at 5 p.m. and I did not arrive until 5:10 so I had to drive another 45 minutes to the nearest crossing point, which was open much later in the evening, so plan ahead for those border crossings. Oh, and don’t try to put anything over on the security personnel. I was the only car in the area at the crossing and did not do a full stop at the stop sign—for which I was severely reprimanded! When I smiled and apologized, the guard simply glowered at me. Welcome back to the United States!)

One of the NWC’s main trading sites was Spokane House, at the confluence of the Spokane and Little Spokane rivers in what is now Riverside State Park near Spokane, Washington (9.5 miles north on highway 291). Established by Thompson and

NWC in 1810, it was the first permanent white settlement in the current state of Washington.

During the following year, 1811, Thompson continued downriver to the mouth of the Columbia, which made him the first non-native (indeed, perhaps the first man ever) to traverse the entire length of the Columbia River from its source near Invermere, British Columbia, north through the precipitous mountains to Revelstoke and then south to Kettle Falls and on westward to the Pacific Ocean.

He was the forerunner for the NWC, which rivaled HBC for domination of the Canadian fur country, and then made a mark in the American fur trade as well.

Down the Columbia to the Pacific

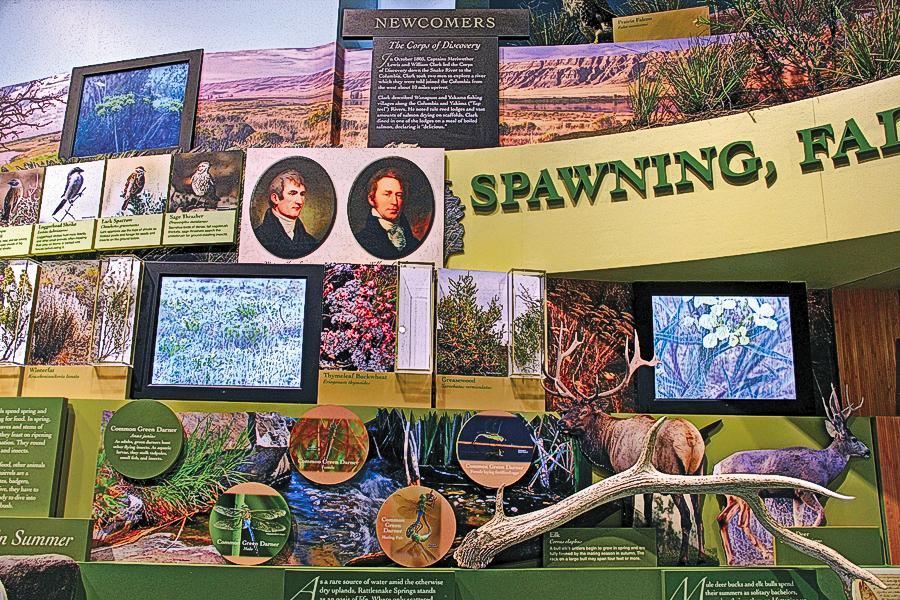

My route takes me from Spokane to Tri-Cities (Pasco/Kennewick/Richland, Washington), site of the newly opened Hanford Reach Interpretive Center, which focuses much of its interpretation on the plants, animals, fish and other critters of the region. Its “Living Land” exhibit, particularly, lets visitors learn more about the flora and fauna and hear stories of connection to the landscape from the perspective of the Wanapum and Nez Perce/Palouse people, as well as fish and wildlife biologists.

Downriver I visit The Dalles, where native people routinely fished for salmon as the signature species of the Columbia drainage moved upriver each year to spawning grounds. I continue on to Vancouver, site of the rival Hudson’s Bay Company post, before reaching the mouth of the river at Astoria. This is where Meriwether Lewis and William Clark wintered. The famed American explorers came to the region just six years before David Thompson arrived.

John Jacob Astor established a trade post for his Pacific Fur Company by 1812 in Astoria, a venture that he sold to the NWC in 1813.

Back Across the Rockies

Thompson explored the Upper Clark Fork in present-day Montana in 1812, where he established Saleesh House near Thompson Falls. Earlier he had established Kullyspel House on the north shore of Lake Pend Oreille, in what’s now Idaho.

After Thompson returned to Canada, the strong rivalry between the NWC and HBC continued, as traders and trappers working for the NWC worked their way down other streams, ultimately taking beaver and other furs in Montana, Wyoming, Idaho and Utah.

One of the better-known fur men, Maine native Osborne Russell, worked for the NWC in Minnesota and Wisconsin, and in 1814 joined the Columbia River Fishing and Trading Company. Under that company’s banner he made it to Wyoming where he trapped along Ham’s Fork and explored Yellowstone country. In 1834, he joined Nathaniel J. Wyeth’s expedition from Fort Hall on the Snake River to Oregon Country. In 1842, he returned to Oregon and settled in the Willamette Valley and helped found the territory. His Journal of a Trapper remains one of the best firsthand accounts of the fur trade life.

Peter Skene Ogden joined the NWC in 1809 as an apprentice clerk. His first station was at Île-à-la-Crosse, Saskatchewan, Canada. He and fellow clerk Samuel Blank tangled with a Hudson’s Bay employee soon after Ogden started his work with NWC, and quickly earned a reputation as a hothead and brawler. By 1814, Ogden was in charge of the post at the north end of Green Lake, about 100 miles south of Île-à-la-Crosse. His brawling turned deadly. Once he reportedly “butchered in a most cruel manner” an Indian who traded with HBC rather than the NWC.

Ogden was indicted for a murder in Canada in March 1818, but when the NWC transferred him to the Columbia department that year, he eluded prosecution. He would ultimately work at Fort George near Astoria, Oregon; Spokane House; and at the Thompson’s River Post near Kamloops, British Columbia.

After the NWC and HBC formed a coalition in 1821, Ogden set aside his earlier rivalry and regained favor with the Hudson’s Bay Company, ultimately being appointed a chief trader. He returned to Spokane House for a time, but then took over operations for the Snake River Country, exploring, trapping and trading in a huge region including present-day Oregon and Idaho, and parts of California, Nevada, Utah and Wyoming. He discovered the Humboldt River in Nevada, saw the Great Salt Lake, and most likely made it into the lower Colorado River country. He took part in a rendezvous at Bear Lake and his name is now associated with a Utah city not far from some of his old stomping ground.

I pick up the trails of Osborne Russell and Peter Skene Ogden by traveling across Idaho to Yellowstone National Park, and then heading south for a visit to the Museum of the Mountain Man in Pinedale, Wyoming. I conclude my travels (more than 2,000 miles round-trip from my home in Encampment, Wyoming) at the Bear Lake Rendezvous in northern Utah, and with a visit to the American West Heritage Center in Logan, Utah, where a primitive camp and recreated fur trader’s cabin, along with a friendly living-history interpreter bring the era to life once again.

Candy Moulton ate at her first Tim Hortons on this trip to British Columbia.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy MtHoodTerritory.com –

– Candy Moulton –

– Courtesy Susan Buce –

– Photos Courtesy Destination BC/David Gluns –

– Candy Moulton –

– Courtesy Destination BC/David Gluns –

– Courtesy Wyoming Tourism –