John Sturges was not a great filmmaker. At least he’s never been placed up there in the top branches with the certifiably best directors—Ford, Hawks and the like. No one would argue that he belongs there, not even his staunchest champions.

But the fact that he does have passionate defenders who are more than willing to argue his many merits is a clue as to why he has a significant place in film history, and that place is due almost entirely to his Westerns.

In the course of his career, which lasted more than 30 years, Sturges made a wide variety of pictures, from low budget suspense films early on to huge Action movies like Ice Station Zebra (1968) and The Eagle Has Landed (1976). But it’s agreed that his Westerns were the best of the lot, several of which will always be found among the top 10 or 20 Westerns of all time. That’s all the defense Sturges will ever require.

Sturges paid his dues, working his way through the Hollywood system, making war films and eventually gaining permission to shoot features. He had no talent for comedy, that was clear, but he developed a great eye for composition, and he managed to get terrific performances from actors. He had a genius for managing ensemble casts, which is why The Magnificent Seven (1960) and The Great Escape (1963) are so powerful, all these many years later.

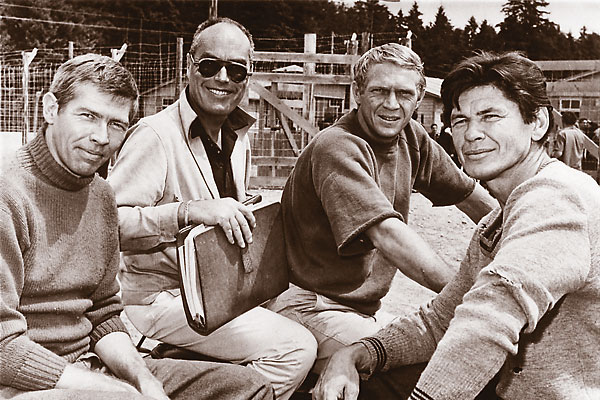

Sturges will be remembered for the way he made stars of actors who were peripheral at the time. Were it not for Sturges, it’s unlikely that James Coburn, Charles Bronson, Steve McQueen and James Garner, who were doing almost exclusively television work at the time, would have risen as quickly or gotten as far as they did in feature film work.

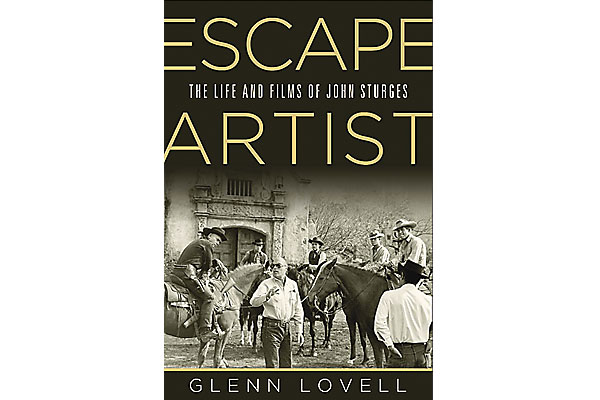

With the publication of Glenn Lovell’s biography Escape Artist, Sturges is finally getting the measure of credit that he deserves. For people who recognize the value of his best movies, Bad Day At Black Rock (1955), The Magnificent Seven, The Law and Jake Wade (1958), Gunfight At the O.K. Corral (1957), The Great Escape, Last Train From Gun Hill (1959) and Escape From Fort Bravo (1953), the films speak for themselves. Most of the pictures on this list are of the sort that fathers have been passing to their sons for several generations; few other Westerns, even the most critically honored, can make that claim.

Glenn Lovell: I think one of the reasons I wanted to write this book is because the scholarship on Sturges has been so shoddy. There are tons of movie books that confuse John Sturges with [filmmaker] Preston Sturges [no relation], for example, and even the IMDB [IMDB.com], which has become a kind of a filmgoer’s bible, has him born in 1911, whereas he was born in 1910. Frank Sinatra Jr., on TCM just a few months ago, was talking about Sergeants Three [a movie Sturges directed starring the Rat Pack] and he said, “this was directed, of course, by John Sturges, who as we all know, is Preston Sturges’s son!”

If you go to the bookstore right now and pick up Robert Vaughn’s book, which is very well-written and has some great stuff in it, he credits John Sturges with directing Somebody Up There Likes Me! [1956, directed by Robert Wise]. There is a real dismissive attitude among critics about Sturges, and what I wanted to explore is, how could a guy be as popular as Sturges, and have made some of these iconic Action-Adventure movies, and come in for such shoddy scholarship?

TW: So what is the reason?

GL: I think the answer is two-fold. I think Sturges himself was not a Hollywood player. Sturges did his work, went home and had another life. And his other life was as a kind of Hemingway-esque figure, who loved deep-sea fishing, did some scuba diving—he was a real outdoorsman. So I think that persona really kept him from being embraced by the industry; and in the end, it hurt him. When you look at The Great Escape and you go into the Oscar book to look and see what was nominated for Best Picture that year, Cleopatra was up, but The Great Escape wasn’t.

The other thing that hurts him is that his style is seamless … it does not draw attention to itself. I’m an auteurist critic, and I love directors with a very discernable style—Robert Aldrich, Anthony Mann. But that’s not Sturges. Sturges let the story tell itself. He always thought he was at his best when he wasn’t showing off and when the technique wasn’t calling attention to itself. You don’t find any artsy shots in Sturges’s films.

The twin rap on Sturges, then as now, is that he was uncomfortable with comedy and uptight around women. He was a good storyteller, but he wasn’t a jokey guy who would pal around with the cast and crew after hours. Everything about him was serious—his demeanor, his face, which was always set. When he smiled, it would startle people, scare them, because it happened so infrequently.

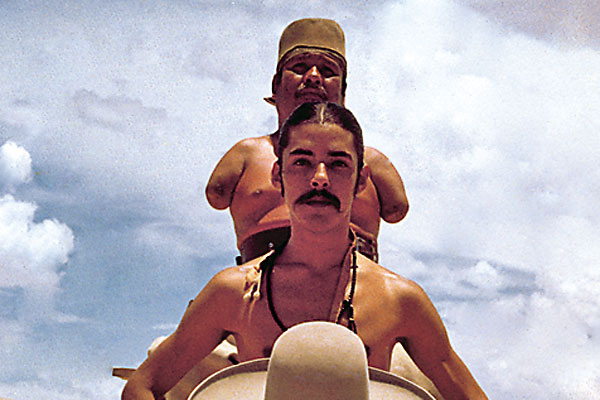

Sturges’s greatest strengths was in atypical casting. It’s still a wonder that Eli Wallach, a largely unknown method actor from New York, was given the role of Calvera, the Mexican leader of the bad guys in The Magnificent Seven.

Sturges had come up with the idea of casting Wallach, and the executive producer Walter Mirisch shook his head at the suggestion, “You’re crazy. He’s a New York Jew, five-foot-four, and never been on a horse!” But as they talked, Mirisch warmed to the idea. Actually, Wallach is five-eight or something.

But there was something about Wallach that he had seen. There wasn’t a lot for Sturges to look at, though [Wallach] had been in Don Siegel’s The Line-Up.

But that’s part of Sturges’s genius for casting. He saw this guy, thought he’d make a great Calvera, and the rest is history. When Wallach gets off his horse at the beginning of The Magnificent Seven, and he walks over to that rain barrel or water barrel, and puts his fingers in and then kind of sucks the water off his fingers—that’s a method moment [laughs]. I couldn’t find that in the script. That was something that he improvised.

One of the great Wallach quotes, he was talking about the Elmer Bernstein score, and he said, “If I’d known the music was gonna be that good, I would have ridden my horse better.”

Mirisch told me that Wallach gave him credit for making the actor a Mexican bandito for life.

That would have been a great quote, but Mirisch tried to shoot Wallach down, and it was Sturges who fought for him. Mirisch couldn’t see it. Sturges was the producer, and he could see it, and Mirisch went along with it.

How did Steve McQueen get cast?

Deborah, Sturges’s daughter, says it was Sturges’s wife who discovered McQueen from the series Wanted: Dead Or Alive, ’cause Sturges never watched television. She was the one who said, “John, you ought to pay attention to this guy.” But that story falls apart when you remember that Steve McQueen was in Sturges’s earlier movie, Never So Few [1959].

You don’t paint a flattering portrait of Charles Bronson in the book. You refer to his tough upbringing in the coal mines and drinking “weed soup.”

Sturges had worked with Bronson before, in The People Against O’Hara [1951], the Spencer Tracy movie, but he didn’t remember him. He was Buchinsky then. He met him all over again for Never So Few, which was the second time they worked together. But Bronson was one of Hollywood’s great misanthropes. Definitely a glass-is-half-empty kind of guy. And Sturges once again—this goes back to how people thought of Sturges as a no-bull kind of guy—he didn’t want to hear a very high paid actor complaining about how terrible life is, and how he had an awful childhood, and he said, “Cut it out! You’re a big star now.”

But Bronson did things his own way. It was really kind of a shame that they ended up making Chino [1973], which has a few good moments in it but which is definitely a failed movie. But here was Bronson, at this point in his career, one of the biggest stars in the world, and he was calling the shots and really making Sturges wait. He’d go into his trailer, or play with the kids in the cast. And here was Sturges, this legendary filmmaker, who had to just sit around until Bronson was bloody well ready to shoot the scene. But that’s Charles Bronson.

I asked Walter Mirisch about that famous anecdote, the one that’s in your book as well, of Yul Brynner telling McQueen to cut the funny stuff, or he’d steal scenes by taking his hat off. Mirisch said Brynner was much too cool to ever see McQueen as a threat.

But Mirisch wasn’t on the set very much. He said he poked his nose in a couple of times, but he made a point of not coming on the set as a way to let Sturges know that he was trusted. I’m sure there was a lot that went on that set that Mirisch didn’t know about.

I interviewed Brynner once when he was touring The King and I, and it was an unpleasant experience, an unpleasant interview. It reached a point where I said, “I don’t think you really want to do this; we can do this some other time,” and finally he said, “No, no it’s okay.”

But he made it be known that he was the driving force behind The Magnificent Seven, and there are probably about 15 people who would step forward, or who at one time could have stepped forward, and challenged that.

What do you suppose makes The Magnificent Seven so good?

For one thing, The Magnificent Seven is incredibly stylized; it’s as much a Musical as it is a Western. It works in the way something like West Side Story worked, which came out around the same time. But when we were kids, we went to The Magnificent Seven and Gunfight At the O.K. Corral, which was also very stylized, and we’d come back home to the backyard and argue who was gonna play Doc Holliday. Doc Holliday was the role you wanted to play.

Gunfight and The Magnificent Seven are very slick, very romantic; they just have a wonderful look about them. But John Carpenter points to The Magnificent Seven as the last hurrah, the last of that kind of film. From then on, it was The Wild Bunch and Spaghetti Westerns.

Another thing, I think you have to keep in mind, especially in The Magnificent Seven, you’ve got Steve McQueen and James Coburn; these are actors who grew up watching movies. They had a movie sense. There was enough of an opening in that script, because it was partially written but not complete, that there was the possibility of improvisation. Robert Vaughn, for example, came up with that great death scene where his cheek slides down the wall—this was a bit of business that Vaughn wanted to try. And it’s the same kind of thing you did when you were a kid, the kind of death you wanted—over the top, theatrical, flamboyant. Certainly, Magnificent Seven is all these things.

The Magnificent Seven and The Great Escape are adult pictures for kids.

I think you’re right. I have a friend who has boys who are 11 and 13. Because she knows of my passion for Sturges and the fact that I’ve been working on this book, she introduced her kids to The Great Escape, and they fell in love with it. It’s a load of fun, really, really a lot of fun. And it really holds up as one of the most entertaining films ever made.

Bad Day At Black Rock may be Sturges’s best picture, but it’s a much more serious film.

I think of Bad Day At Black Rock as a Western as well, a modern-era Western, as it takes place in the months just after the end of WWII. Whenever Bad Day At Black Rock came up, Sturges said, “It doesn’t get any better than that. The screenplay came to me and we didn’t have to change anything. It was perfect.” But what Sturges did was, they got rid of a lot of secondary characters in the town. There were other people with lines, but he pared them away, and that was, again, part of Sturges’s genius. He talked about making it into a Greek tragedy by just having X number of players, and only those characters who are intrinsically involved in the moving of the plot would survive those edits.

David Thomson said that the Western was the genre Sturges did best.

Well, as a kid [Sturges] read Western pulps and played cowboys; certainly, he grew up watching the great silent Western stars, so it was a natural for him. And he spent some time on a kind of a dude ranch when visiting a friend when he was a kid. He had a love of the outdoors instilled in him by his mother Grace. When you have that, you’re naturally drawn to the Western.