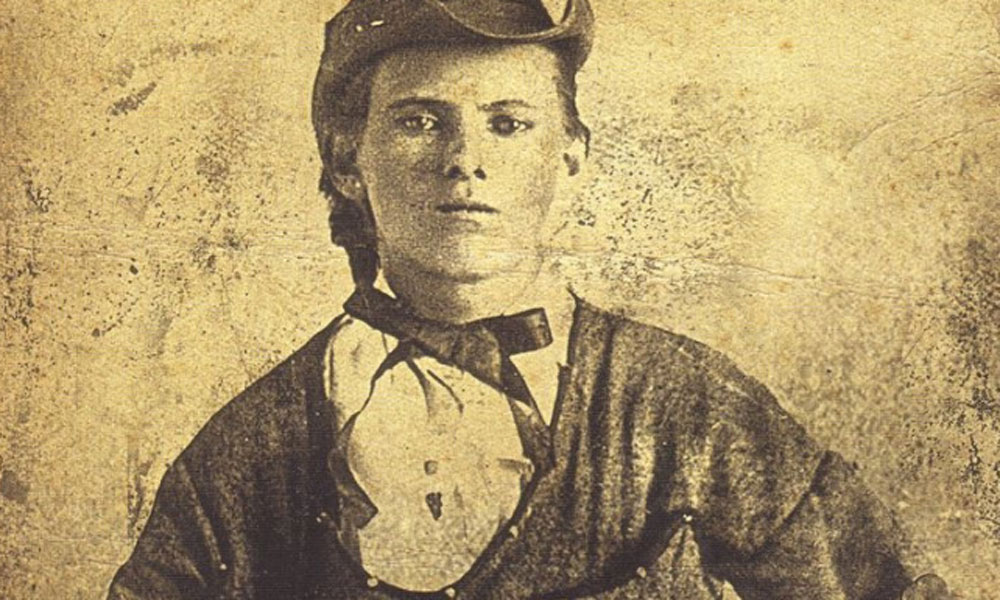

Jesse James dug his spurs into his horse, pushing for speed while bullets flew past his head.

Jesse James dug his spurs into his horse, pushing for speed while bullets flew past his head.

For two weeks, Jesse had been running and hiding from the largest posses ever in American history—a group more than 1,000 strong. Now, part of that posse chased hot on his heels. Things went from bad to worse for Jesse when he saw a 20-foot wide chasm called Devil’s Gulch directly in front of him. The 60-foot deep canyon carved out of jagged pink quartzite cut off his only escape. Death or capture seemed his only options, but Jesse found another. He sprinted toward the fissure. At the last moment, he rose in the saddle, urged his horse skyward and jumped safely to the other side. Amazed, and too scared to follow, the lawmen stared dumbstruck as Jesse cantered off to freedom.

That’s what really happened … maybe. Supporters point to evidence both anecdotal and circumstantial to prove the jump. Hundreds of eyewitnesses placed Jesse near Devil’s Gulch, inside the small town (pop. 1,000) of Garretson near South Dakota’s eastern border. He and his brother Frank fled there after their disastrous bank robbery in Northfield, Minnesota, on September 7, 1876.

Yet historians remain skeptical. Many think the chasm too broad for any horse to jump. Also, consider the Jesse James mystique. More tall tales surround him—in life and in death—than perhaps any other historical figure. So the debate continues. Did Jesse jump Devil’s Gulch, or did he just jump into history?

Prelude: Northfield Raid

The Northfield bank robbery proved disastrous for the James-Younger Gang. Frank and Jesse, with their longtime partners the Younger brothers—Cole, Bob and Jim—traveled to Minnesota from their homes in Missouri. Two others, Clell Miller and Charlie Pitts (alias Sam Wells), accompanied them.

There they met Bill Chadwell (a.k.a. Bill Stiles), a Minnesota resident who likely persuaded them to come. “Stiles probably told them about all the banks up here full of money and not well protected,” says Hayes Scriven, executive director of the Northfield Historical Society. “He likely said something like: ‘They’re only a bunch of dumb farmers who wouldn’t know an outlaw if one bit them in the foot. It will be a walk in the park.’”

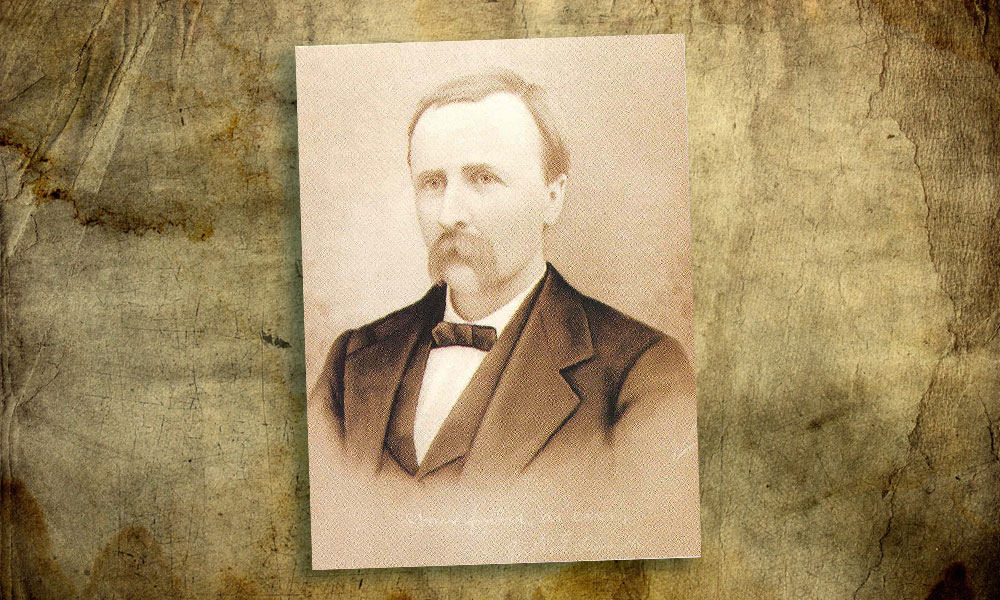

The heist proved anything but easy. The gang’s plan derailed immediately when the acting cashier, Joseph Lee Heywood, refused to open the safe. The bandits cracked open Heywood’s skull with a pistol butt, but he still refused to comply. Meanwhile, townspeople sounded the alert. Northfield resident J.S. Allen ran around yelling, “Grab your guns, boys. They’re robbing the bank.” Citizens, armed with guns and rocks, stood on guard to protect their money.

For the frustrated and nervous outlaws, their escape time was growing short. They grabbed all the cash they could—just $26 and change from the till—and ran outside. Someone, reportedly Frank, paused long enough to shoot Heywood in the head, killing him. Bullets immediately rained down on them from nearby buildings. Chadwell and Miller died. Jim took a bullet in the shoulder, while Cole got his in the hip. Frank got shot in his right leg. Bob’s elbow shattered.

The gang wanted to escape north where they planned to cut the town’s telegraph wires. Well-armed men protected that route, however, so after a brief firefight, the gang changed direction and fled west.

Their path after this point becomes murky. “Nobody knows why they went west,” says Earl Weinmann, tour coordinator at the Northfield Historical Society and the editor of Caught in the Storm, a book that follows the outlaws’ path through Minnesota. “Perhaps they got lost or were just trying to elude pursuit.”

Three problems plagued the gang’s escape. First, the weather proved dreadful, raining for 14 straight days. Second, with Chadwell dead, nobody knew the area. The outlaws stumbled through a series of small towns and stopped at farms looking for food and asking for directions. With the constant rains swelling rivers, they seemed particularly interested in locating bridges.

Their final, and most dangerous, problem was the posses. With their telegraph intact, Northfield alerted all of Minnesota to the robbery. Governor J.S. Pillsbury issued a statewide alert that read: “Wanted dead or alive. $5,000 will be paid for the capture of the men who robbed the bank at Northfield, Minnesota, believed to be Jesse James and his band or the Youngers. All officers are warned to use precaution in making arrest. These are the most desperate men in America. Take no chances! Shoot to kill!”

Hungering for reward, most able-bodied men in southern Minnesota joined the search, but it was a disorganized mess. One newspaper editor called it, “An undisciplined mob of men and boys, with here and there a sheriff or policeman.” They stumbled through cornfields, shouting to one another in Norwegian, German or English. Realizing the extent of the manhunt, and its limitations, the gang correctly decided it would be easier to avoid detection on foot. They abandoned their horses and successfully eluded search parties for nearly a week.

The enormity of the manhunt, if not its efficiency, gave the gang constant worries about accidental discovery. That’s exactly what happened on the night of September 13, near Mankato. Jeff Dunning, a local farmhand, was out searching the woods for stray cattle when he stumbled onto the outlaws’ camp. They tied him up in a leather bridle and forced him to locate area bridges.

Next came the question of what to do with Dunning. Jesse and Frank wanted to kill him. Cole, Jim and Charlie felt inclined to let him go. Bob provided the swing vote. Thinking hard for several minutes, Bob soberly decided: “I would rather be shot dead than to have that man killed for fear his telling might put a few hundred after us. There will be time enough for shooting if he should join the pursuit.”

The next day, the James-Younger Gang split up … forever as it turned out. Before sunrise, Jesse and Frank stole a horse from a nearby farm and galloped off together on bareback. Soon after, they encountered a picket line of guards. All the sentries were sleeping, save one. Richard Roberts spotted them creeping past. He noticed the rear rider bore a white bandage around his right leg. Roberts yelled for the pair to stop. They ignored the call and sped onward. Roberts fired. “The horse halted, throwing the two riders onto the muddy road,” Roberts said. Afterward, Roberts found a hat with a bullet hole in it. “Subsequent events convinced me the hat belonged to Jesse James, and the rider with the white bandage on his leg was his brother Frank.”

The shot woke the other guards. They haphazardly followed the James brothers into an adjacent cornfield, but the pair easily evaded the guards. Frank and Jesse stole another horse and continued west.

That fracas drew all eyes onto the James brothers, which may have been their plan. Weinmann, like other historians, thinks the gang “orchestrated the debate about what to do with Dunning because they knew he’d go tell the posse, and because they knew Frank and Jesse were going to leave the next day. The posse would follow Frank and Jesse, and that would divert attention from the others who were far more injured and moving very slowly on foot.”

The plan nearly worked, except that 17-year-old farm boy Oscar Sorbel noticed the four men walking by the farm on September 21. Sorbel alerted a posse of 100 men, who cornered the outlaws at Hanska Slough. Charlie Pitts died in the ensuing gunfight. Cole, Jim and Bob surrendered. The Youngers were sentenced to life imprisonment. Bob died inside, in 1889. Cole and Jim received parole in 1901.

Meanwhile, the James brothers covered more than 120 miles of rain-soaked farmland in a circuitous pattern on unfamiliar horses and ended up near Luverne, on or around September 17. There, Frank and Jesse visited C.B. Rolfe’s ranch. Mrs. Rolfe, home alone, noticed one walked with a limp and both looked “badly roweled.” The men requested breakfast. She complied. While she cooked, the brothers asked her questions about the area. They also asked, “if being away from the telegraph and near Indians wasn’t a problem.”

The encounter appeared in The Luverne Herald the following year. It reported that: “Though polite, they were not inclined to loquacity and from the first Mrs. Rolfe suspected they were the Northfield bank robbers.” After telling Mr. Rolfe, “He started immediately for Luverne to arouse the people and institute peril.”

The townspeople quickly formed a posse, and “rusty firearms and forgotten revolvers were dragged forth.” One member, Martin Webber, called the group a bunch of “indifferently-armed farmers.”

The Rock County Herald detailed the pursuit in its September 23, 1876, edition. It related how one night the posse almost accidentally sought refuge in the same house Frank and Jesse occupied. The posse, it surmised, “barely missed what doubtless would have proved a bloody encounter at this place.”

The next morning, Frank and Jesse “had only a 15-minute head start,” and “the chase at once became warm.” Around this time, Frank and Jesse visited Andrew Nelson’s farm just across the border in Dakota Territory. Andrew’s son, Nels, who was then 13 years old, remembered the pair arriving in the early evening asking for water. Nels filled a bucket for Jesse’s horse. Nels then offered to retrieve a clean bucket for Jesse, but he was turned down. Nels said, “I can remember clearly the words of the outlaw: ‘I reckon I’d rather drink out of a pail used by a horse than some men I know.’” Then Jesse drank.

The Nelsons knew nothing about the Northfield robbery, so they felt no reason to be suspicious. The next morning, however, they found their own horses stolen.

Escape at Devil’s Gulch

The posse—probably about 20 members strong—caught sight of their quarry and gave chase, but at a distance. None of them felt like risking their lives to approach very close. The Rock County Herald singled out Jack Dement as the “hero of the occasion.” Dement “rode a little nearer to the robbers than was agreeable to the latter, and suddenly turning they fired five or six shots in rapid succession, one which passed through the neck of the beast that Jack rode.”

It was probably at this moment that Jesse jumped Devil’s Gulch, if indeed he did. Gary Chilcote, the museum director at the Jesse James Home in St. Joseph, Missouri, doubts it occurred. “It’s a wonderful story, but there’s no way a horse could jump it,” Chilcote says. “I call it ‘fakelore.’ It’s one of those fascinating stories about Jesse James that persists. All his life and death are filled with stuff that could have happened but likely didn’t.”

Hayes Scriven agrees, saying: “It’s nearly 20 feet across! Jesse would have needed a jet pack to jump it.”

Both men also cite the rocky terrain, sharp corners and uneven ground as making the jump unlikely.

Gordon Aaker, a volunteer at the Devil’s Gulch Information Center, disagrees. “A high school long jumper can jump over 20 feet, so I think it’s certainly possible for a horse to do it,” he says. Indeed, horses have been recorded jumping more than 27 feet. Years ago, when Garretson hosted the Jesse James Stampede Rodeo, many professional horsemen believed the jump physically possible but still improbable.

Jesse certainly possessed enough skill in the saddle to make any horse do the incredible. Universally considered an expert rider, if any historic figure could jump the canyon, Jesse could.

Aaker also notes that the canyon ledge looked very different in 1876 than it does today. “We have old photographs that show the place as having level ground gently sloping from one side to the other. That would make the jump easier.”

The jump gains roundabout credibility from the posse’s testimony. All accounts placed the posse in pursuit right around Devil’s Gulch when the chase abruptly and inexplicably stopped. The Luverne Herald simply stated the pursuers “lost the trail.” The Rock County Herald noted: “The pursuit was continued for several miles, when, finding no trace of the outlaws, the party gave up the chase and returned.”

Garretson’s locals fill in that mysterious gap as being Jesse’s jump over the gulch. Aaker remembers the handful of women who, several decades ago, first took steps to preserve the town’s Jesse James connection. “They said they found some signed documents from the posse in the Luverne courthouse testifying how Jesse made the jump but none of them dared follow,” he says. “By the time they went around the canyon, it was getting dark and none of them wanted to be out in Indian country for the night, so they headed back.”

Perhaps the posse got scared and turned back. Martin Webber said, of the shots into Jack Dement’s horse, “This, as I remember it, ended the pursuit.” Keep in mind, though, that the men lived for decades in the area, long enough to hear the story popularized. None spoke out against any fabrications. “They never changed their story,” Aaker says, “not even on their death beds.”

Silence, however, does not constitute proof in men or in documents. The signed testimony cannot be found in the Luverne courthouse. Furthermore, the ladies never let others see the papers. “They always said not to worry about copies, because they knew what they said,” Aaker remembers. “Well, they died, and we don’t know what happened to the documents.”

The papers may be nothing more than details invented to make “fakelore” more believable. “People want to believe they have stories that tie them in to Jesse James somehow,” Chilcote says. “Here’s this little town with not much going for it, but they have this story that people all over the world have heard of.”

Today, thousands of people visit Garretson every year to see Devil’s Gulch. They buy shirts and mugs, which helps the local economy, although certainly nobody’s getting rich.

Gary Chilcote also notes that Garretson and Northfield are just two of many towns profiting off the Jesse James mystique. “Jesse James brings in more money now than he ever did when alive, even with all his thefts.”

Individuals may mirror these towns in wanting some connection to Jesse James. How else to explain the hundreds of Minnesota families still telling how their great-great-grandparents met the outlaw? The stories usually include the pair stopping for food, drinking water, stealing horses and giving the wife a silver dollar. “If Jesse stopped and ate at every place they said he did, he would’ve weighed over 500 pounds,” Scriven jokes.

Most stories also include that the James brothers lied and introduced themselves as members of the posse. Weinmann doubts the visitors lied. “There were 1,000 men chasing the outlaws, and they stopped for food too. That was common practice then. Well, since nobody knew what the James boys looked like, and since people tend to romanticize things, it’s easy to look back and think: ‘Those were the outlaws.’”

Logistics also question the jump’s plausibility. Although the outlaw was indeed a master rider, would Jesse risk jumping on an unfamiliar horse? He probably rode a typical plough horse—strong enough but hardly a jumper. Nels Nelson remembered the animals as “only farm plugs.” Also, one horse in the Nelson team was blind in one eye, and the other was completely blind.

Finally, why would Jesse jump when he’d already proven he could outride and escape all pursuers? Devil’s Gulch continues on either side for only half a mile or so. A horse could ride around in short order.

So, for lack of evidence, the jump over Devil’s Gulch becomes, as Chilcote says, “the best known piece of Jesse James lore that you can never prove or disprove.”

The truth, or lack thereof, behind anything happening at Devil’s Gulch should not tarnish what remains—with or without the jump—an incredible tale of escape. The Rock County Herald begrudgingly bestowed its admiration upon the outlaws, noting: “These two bold desperados have ridden a distance of nearly two hundred miles through an open prairie country, unscathed, showing a power of endurance that seems almost superhuman, and which challenges the admiration of all those who have been engaged in the pursuit.”

Weinmann adds, “It’s a testament to how good of riders they were, because they were riding some pretty lame horses, and they still managed to escape a posse 1,000-men strong and return safely home sometime in early October.”