Colorado Territory, February 1874.

Fictional frontier doctor Elijah Baines sat quietly at the bedside of his 64-year-old female patient Sarah, who had just fallen on ice the day before and hit her head.

He had already cared for the small laceration on the side of her scalp with four catgut sutures. He was now worried that her unrelenting headaches and sleepiness were signs of a concussion and possibly bleeding on her brain.

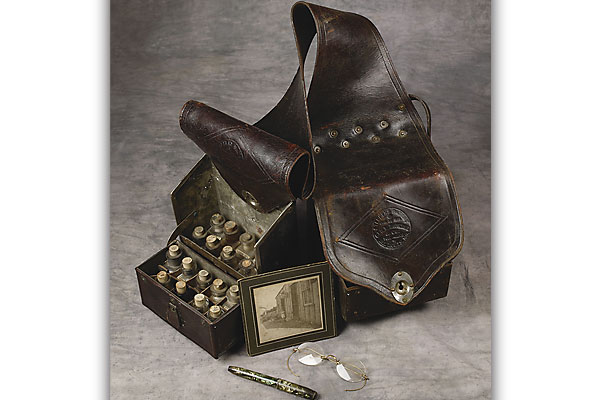

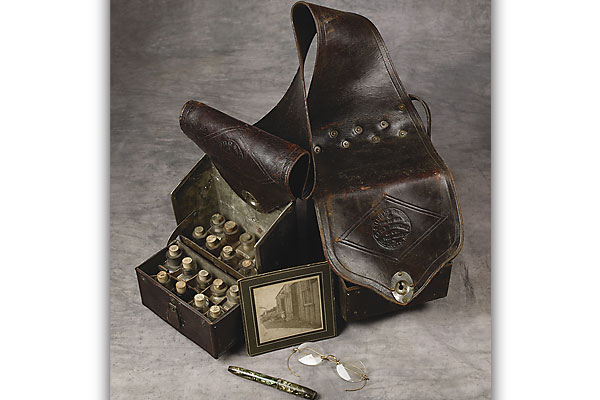

He reached from his chair into his large, almost suitcase sized, black leather bag to fumble around for his new ophthalmoscope. He intended to look at the back of his patient’s eyes (retina) to see if the vessels were sharp and whether the head of the optic nerve was easily distinguishable. Next, he reached for his otoscope to examine Sarah’s eardrums to see if there was any blood behind them.

In performing these examinations, Dr. Baines would know his patient’s prognosis and whether he would need to consider the drastic and deadly procedure of drilling a hole in her skull to relieve the pressure. He had the drills, called trephines, to perform this surgery, but he had only completed this procedure six times before in his 20 years of practice and five of his patients had died.

After his examination, Dr. Baines’ worst fears were realized. He had not yet told the family, gathered around the stone hearth in the next room. He rose from the bedside, wiped his brow and headed to face a timeless challenge as great as treating his patient’s epidural bleed.

Categorically, the contents of Dr. Baines’ black bag were somewhat different from those found in the bags of most modern day physicians. The frontier doc did not work within a supportive, comprehensive medical care system consisting of pharmacies, ambulances, hospitals and flight for life helicopters. For the most part, he had to be prepared for and do just about anything and everything.

To understand the contents of the frontier doc’s black bag, it is best to try to understand those things that he would be expected to do. Once he interviewed the patient or family, he would perform his physical examination. He needed tools to examine the eyes (ophthalmoscope), the ears (otoscope), the throat (tongue depressor), the heart and lungs (stethoscope), the reflexes (reflex hammer) and other parts of the nervous system (pins and brushes, for sensory testing). His usual light source was his head mirror used to reflect the light from the sun or the patient’s lantern or candle. Following his physical examination, he formed his diagnosis and then decided how best to treat his patient.

It is in the area of treatment that the frontier doc’s black bag differs most from the bag of the modern day physician. The frontier doc usually carried the best multi-specialty equipment of the day. He carried scalpels for cutting and therapeutic bleeding, obstetrical forceps for delivering babies, glass suction cups for treating his patients with lung disease (cupping), needles and glass syringes for giving shots, assorted slings and splints, and a wide variety of medications. These included mercury and arsenic based compounds to fight infections, laudanum (opium) for pain, various herbal preparations, skin salves, leeches for bleeding and even whiskey to treat the patient, the family or even himself!

Some doctors had developed their own special tools to treat everything from warts to skin cancers. The frontier doc’s bag contained a wide variety of surgical instruments, including suture materials and needles, hemostats for clipping off blood vessels, along with probes and extra long forceps to remove bullets and other foreign objects.

The frontier doc’s black bag was a credit to his skills, devotion and the risks that his patients were willing to assume. Whatever the outcome, Sarah’s trust in Dr. Baines was about all that she could hope for, a scenario that has changed little in the past 134 years.