– True West Archives –

What better adventure than to follow the trail blazed by Woodrow Call and Gus McRae—plus Dish, Deets, Newt and my personal favorite, Pea Eye Parker?

Oh, wait. Larry McMurtry won a Pulitzer Prize for his 1985 novel, Lonesome Dove, but that’s fiction. The real trail, and the real history, belonged to Charles Goodnight and Oliver Loving. It didn’t lead to Montana, but first to New Mexico, then Colorado, and eventually Wyoming. And now, 150 years after that first cattle drive along the trail, it’s time to retrace the route.

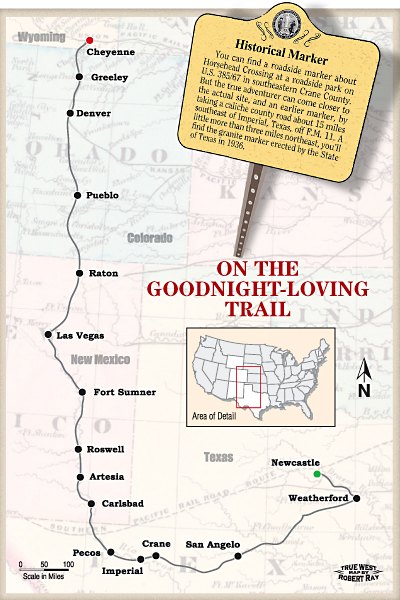

“The trace that led from Texas to Fort Sumner is generally known as the Goodnight Trail,” J. Evetts Haley wrote in his monumental biography Charles Goodnight: Cowman and Plainsman, “while that which Goodnight later blazed direct to Cheyenne is called the Goodnight and Loving Trail, though sometimes the terms are used interchangeably.”

Like with many trails, the route changed over the years, depending on water, grass and the fact that Goodnight didn’t like paying “Uncle Dick” Wootton a dime a head at Wootton’s toll station at Raton Pass on the Colorado-New Mexico border.

The trail begins in Young County, Texas, in Newcastle. Now Newcastle did not come about until the early 1900s when settlers came to work for the Merrill and Clark Strip Mining Company. Before that, however, Fort Belknap stood guard along the Brazos River. Founded in 1851, the fort bustled with activity because nearby roads—including John Butterfield’s Overland Mail route—led out in all directions.

The fort was permanently abandoned in 1867, and could have just disappeared. In 1936, however, Senator Benjamin Oneal and a bunch of locals decided to restore and rebuild some of the buildings as a state centennial project. Still a county park, the old grounds include restored buildings, while the Fort Belknap Cemetery includes the grave of Major Robert Neighbors—who fought for the rights of Comanches, and paid the ultimate price when a white settler murdered him for his support of the Indians in 1859.

But this story isn’t about Neighbors. It’s about two other intriguing figures who teamed up in 1866 to make history and legend.

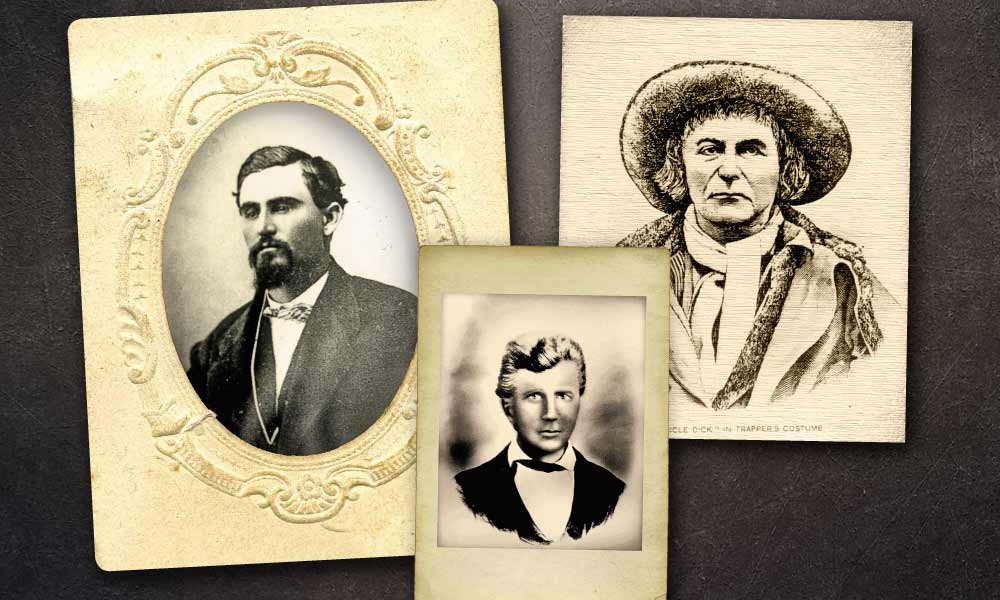

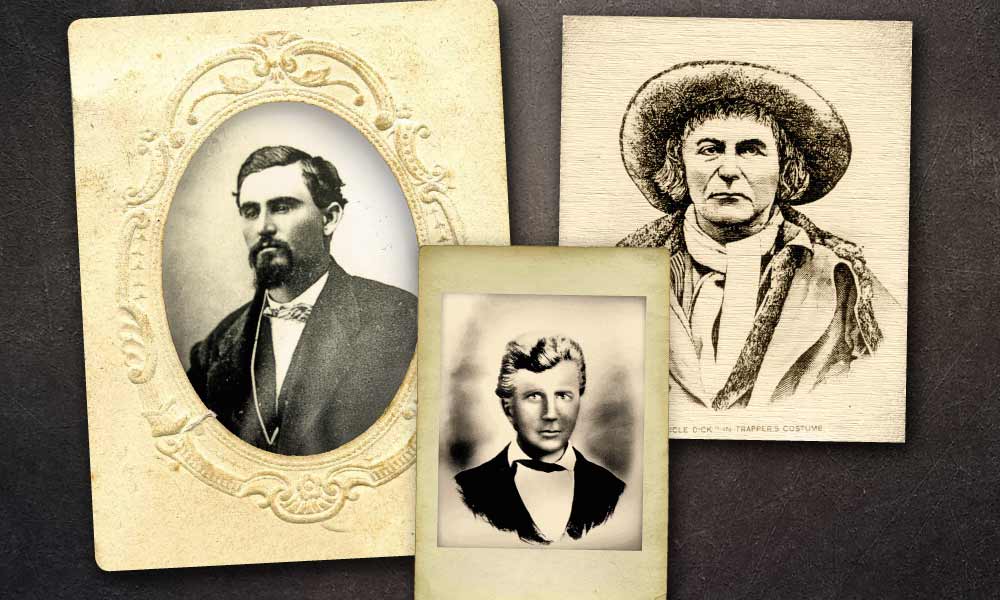

Partners: Oliver Loving and Charles Goodnight

Kentucky-born Oliver Loving arrived in Texas in 1843 when he was 30. Loving drove cattle to Denver in 1860, and the Confederacy commissioned him to drive cattle to Rebel forces on the Mississippi River. The government was said to have owed him between $100,000 and $250,000 when the war ended.

Born in Illinois, Goodnight had to grow up fast when his father died of pneumonia in 1841. Goodnight was just five years old. The family moved to Texas four years later, and by the time Goodnight was 11, he was working on farms. As a young man, he entered the cattle business.

In 1866, Navajos and Mescalero Apaches were at the Bosque Redondo reservation—a concentration camp, Indians would say—near Fort Sumner, New Mexico Territory. Goodnight figured he had found a new market for beef.

When Goodnight approached Loving with the idea, the elder man warned him of the dangers. Goodnight remained undeterred, so Loving told him, “If you will let me, I will go with you.”

They joined forces, and on June 6, 1866, 18 men and 2,000 longhorns started the

drive about 25 miles west of Belknap.

Talk about an all-star cast. “One-Armed” Bill Wilson, who would survive a harrowing escape from Indians in 1867. Cross-eyed Nath Brauner, who made a habit of killing rattlesnakes. A black cowboy named Jim Fowler, who drew the grim chore of killing newborn calves that would be unable to finish the drive. And former slave Bose Ikard, whose epitaph was written by Goodnight when the loyal cowhand died in 1929: “Served with me four years on the Goodnight-Loving Trail, never shirked a duty or disobeyed an order, rode with me in many stampedes, participated in three engagements with Comanches, splendid behavior.”

Ikard’s grave can be found in the Greenwood Cemetery in Weatherford, near Loving’s grave.

The herd followed the Overland Route from Belknap through Castle Gap in Upton County, to the Pecos River, then along the Pecos to Fort Sumner.

West Texas

West Texas remains tough country, but you’ll find an oasis in San Angelo, home of the excellent Fort Concho National Historic Landmark; shops and galleries (but no overnight accommodations) at The Cactus Hotel, Conrad Hilton’s fourth hotel; murals throughout town; Miss Hattie’s Bordello Museum; and plenty of Elmer Kelton novels for sale, which you would expect in the late, great Western novelist’s hometown.

After their grueling journey, the Goodnight-Loving drive reached the Pecos River. For days, the cattle crew moved along the east side of the Pecos, “the most desolate country that I had ever explored,” Goodnight observed.

It hasn’t changed much. Which makes the town of Pecos a welcome reprieve.

First established as a cow camp, the town of Pecos wouldn’t boom until the 1880s, but it’s worth a stop today to visit the grave of gunfighter Clay Allison and the West of the Pecos Museum, housed in an 1896 saloon and a 1904 hotel.

At the Pecos, the trail crew left Butterfield’s road and moved north along the Pecos River. The best-known crossing was Horsehead Crossing, one of the few places where people could safely ford the river in present-day Pecos and Crane counties, south of the town of Pecos. Farther northwest, however, Pope’s Crossing was on the Loving-Reeves county line just south of New Mexico, was Goodnight and Loving’s choice. Used by Spanish explorers and California gold-chasers, Pope’s Crossing was named for Captain John Pope, who led a survey crew in 1854. The crossing disappeared in 1936 with completion of Red Bluff Dam and Reservoir.

The Land of Enchantment

Following U.S. 285 near the Pecos River takes you into New Mexico. To Loving (we’ll talk about it later). To Carlsbad (consider a deviation from the route to Carlsbad Caverns National Park).

Travel through the bleak countryside to Artesia, once home to Sallie Chisum, the niece of another famed cattleman, John S. Chisum. At a gas station on First and Main stands Vic Payne’s 2007 monumental sculpture Trail Boss, which honors Goodnight and his legacy to the area.

Then, proceed to Roswell, known more for crashed alien spaceships and the International UFO Museum and Research Center. And finally to Fort Sumner, best known as the end of trail for Billy the Kid. The town has two Billy museums and the graves of Billy and a couple of his pals—not to mention a marker for Joe Grant, shot and killed by the Kid in a local saloon in 1880.

Loving and Goodnight came here for the fort and reservation, now excellently preserved at Fort Sumner Historic Site and the Bosque Redondo Memorial. But government contractors and subcontractors wouldn’t buy the stock cattle. They paid eight cents a pound for the steers, netting $12,000, which left the cattlemen with 700 to 800 cattle. Goodnight returned to Texas, and Loving pushed the cattle on for Colorado, past Las Vegas and Raton, and to Denver, where Loving sold the cattle to John W. Iliff.

The next year, Goodnight and Loving organized another drive. Indians and rains slowed the cowboys in 1867. Along the Pecos, Loving and “One-Armed” Bill Wilson rode out ahead. Indians attacked…and since everyone has either read and/or seen Lonesome Dove, you know how the story ends.

That brings us back to the New Mexico village of Loving, which went through a number of names (Vaud, Florence) before the name was changed to honor Loving. No one knows for certain where Loving was wounded. Wild Cat Bluff? Loving’s Bend? Just like no one knows why this place was once Florence (a city in Italy, or after Loving’s daughter).

End of the Trail

Back to the Indian fight: Loving, seriously wounded, sent Wilson back to the herd. Wilson’s escape was epic, but overshadowed by Loving’s story. Mexican traders found Loving and got him to Fort Sumner, where he died of gangrene on September 25. Goodnight took the cattle north to Trinidad—where today the A.R. Mitchell Museum of Western Art and the Trinidad History Museum are musts. Goodnight established a ranch and cattle-relay station 40 miles northeast of town. In February 1868, Goodnight loaded Loving’s coffin into a wagon and brought him back to Texas for burial, “the strangest,” Haley wrote, “and most touching funeral cavalcade in the history of the cow country.”

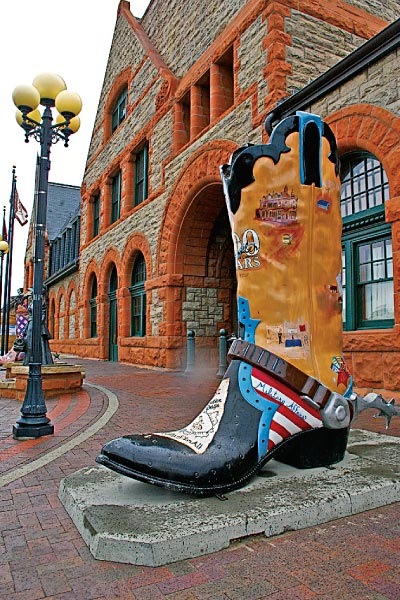

Later that year, Goodnight contracted with Iliff to bring cattle to Cheyenne, Wyoming, and the Union Pacific Railroad. So the trail got longer, moving from Pueblo, east of Denver, to the South Platte River. Past Greeley—check out Greeley Hat Works, making great hats since 1909—and then following Crow Creek to Cheyenne, among the West’s most Western burgs.

“By 1870,” Haley wrote, “the trade along the Goodnight and Loving Trail was well established, and the amount of money handled by its Western bankers was noted as enormous.”

You can find a roadside marker about Horsehead Crossing at a roadside park on U.S. 385/67 in southeastern Crane County. But the true adventurer can come closer to the actual site, and an earlier marker, by taking a caliche county road about 15 miles southeast of Imperial, Texas, off F.M. 11. A little more than three miles northeast, you’ll find the granite marker erected by the State of Texas in 1936.

– All images courtesy Johnny D. Boggs unless otherwise noted –

Johnny D. Boggs re-creates another trail drive in Return to Red River. His book, a sequel to the novel by Borden Chase that became the classic John Wayne movie Red River, is due out later this year from Kensington.