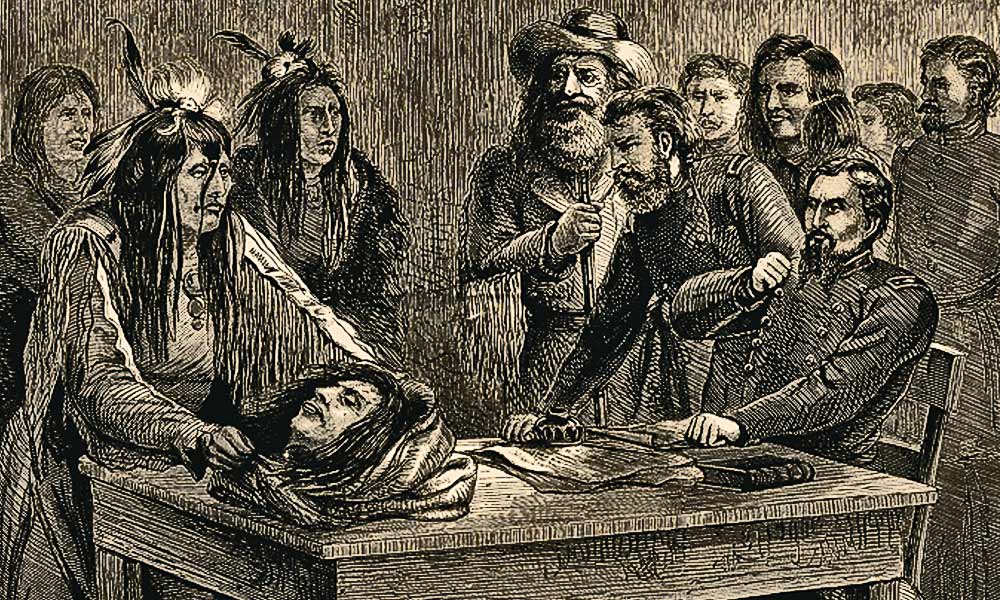

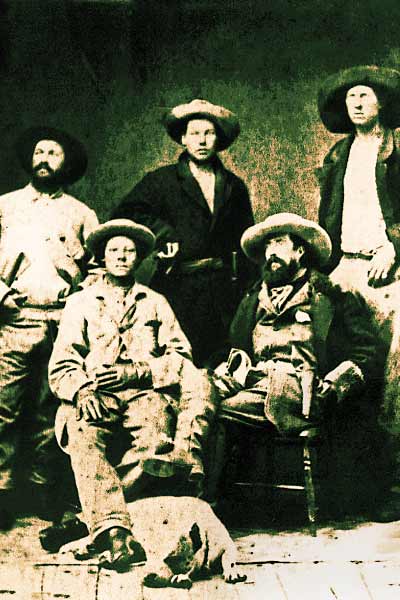

– Published in Harper’s Weekly, April 30, 1870 –

Whether due to a break in the weather—the thermometer had gone as low as -43 degrees Fahrenheit—or just because they had no more time to waste if they wanted an element of surprise, on Wednesday morning, January 19, 1870, 2nd U.S. Cavalry Maj. Eugene M. Baker and his command moved out the gates of Fort Shaw to proceed toward the first low hills and across the frozen plains of Montana Territory in quest of the Piegan Indians.

A murder had put the town of Helena in an uproar. Pete Owl Child of Mountain Chief’s band, with a small group of Piegans, visited Malcolm Clarke’s ranch near Helena. The Indians lured Malcolm and his half-blood son, Horace, outside their house on the night of August 17, murdering Malcolm and leaving Horace for dead, but he lived to tell the story.

Most of the new citizens around Helena, many of whom had only recently arrived, knew that Malcolm had a Piegan wife whose brother was Pete Owl Child. They were the children of Mountain Chief. Some stated that Pete Owl Child had good reason for his savage attack: Malcolm had beaten him and seduced his wife.

Lieutenant Gen. Philip Sheridan’s blood-chilling order came on January 15: “If the lives and property of the citizens of Montana can best be protected by striking Mountain Chief’s band, I want them struck. Tell Baker to strike them hard.”

With a force numbering about 380 men, Baker and his command moved slowly through the numbing cold toward the Marias. The Army and Navy Journal printed that “the thermometer still indicated severe weather, but the men, anticipating a brush with the Indians, were so excited that if the mercury had been frozen they would not have heeded the cold.”

Martha Plassmann, a journalist, gave her opinion later that other reasons may explain how the soldiers got through the cold: “One of the company told me that officers and men ‘tried to keep their spirits up by taking spirits down’ and, at the end of the journey they scarcely knew what they were doing.”

Dissension Breaks Out

Sometime during the night of January 22, dissension broke out between Baker and the guides. That evening Joe Kipp protested that the trail they were on would not take them to Mountain Chief’s camp, but rather to the smallpox camp of Heavy Runner. Kipp had apparently made a mistake or had wrong information, and he now tried to convince Baker of his error. A drunk Baker thought that Kipp was deceiving him and threatened to shoot him if he did not lead as directed.

Baker’s column was in confusion by the time it reached the bluffs above the Marias River on January 23. Baker was drunk and could not comprehend the directions that his guides were giving him or perhaps just chose to ignore them, with some justification, because each guide may have had his own agenda. Kipp, for instance, was also in the fur trade and closely aligned with the interests of the whiskey traders.

In actuality, Kipp’s information came to him just recently. He had gone out with guides Horace Clark and Joe Cobell to try to find the location of Mountain Chief’s camp. During this search Horace had a surprise encounter on the bluffs with John Middle Calf, 19, a member of Heavy Runner’s band. Middle Calf revealed that Mountain Chief had moved about nine miles below on the river because the whiskey trader Jerry Potts had warned the band about the soldiers coming.

That such an action might occur was, in fact, predicted by the military. On January 13, Brig. Gen. Alfred Sully had already advised Inspector Gen. James A. Hardie that it would “be a difficult matter to make any movement without the Indians getting information through the half-breeds and whisky-sellers at Sun river and Benton.”

The Surprise Attack

After an argument with Baker on the trail, all three guides were sent to the rear, leaving Baker and his troops to find their own way. The problem that Baker would have in leading, even if he was sober enough to command, was that the troops could not simply ride down the river bottom until they reached the camp. Baker was committed to an early morning surprise attack and wanted his command on top of the bluffs, where he could fire down on the Indians when they were found. Without Kipp, Cobell or Clarke to guide them, all that the companies of Baker’s command could do was proceed on a parallel course with the river, as close to the edge of the ravine-cut bluffs as possible, while still remaining out of sight.

Captain Lewis Thompson and L Com-pany were the first to reach the Marias. As the company rode down a coulee to the river bottom, an Indian lodge suddenly appeared, surprising them. Private John Ponsford, 22, was with Lt. Gustavus Doane’s F. Company as they too approached the Indian lodge and said that he “thought we had arrived at [Mountain Chief’s] camp.” When he heard the order given “to fight on foot,” he eagerly jumped from his horse and rushed with the dismounted troops to the camp. Then they suddenly stopped, aware that something was amiss.

As they looked around, they expected to see other lodges of Mountain Chief’s band. Instead they felt only an eerie stillness around them and soon knew the reason. As a few frightened Indians emerged from their tipi, their smallpox was evident.

Instead of Mountain Chief’s larger camp, the troops had found the small camp of Gray Wolf. The soldiers learned that “a large band of their tribe was encamped about ten miles distant on the Big Bend of the Marias.” Thompson seemed sure that he could still find Mountain Chief and gave his troops the command to proceed on their mission.

Thompson’s L Company kept pushing down the top of the bluffs that morning, but Doane’s F Company had taken over the lead.

The Work of Slaughter

As the troops advanced along the trail, the guide Kipp appeared, protesting once again that the trail they were on would not take them to Mountain Chief, but rather to the camp of Heavy Runner. He was taking a chance by even being with the troops at this point, for fear that Baker might carry out his threat to shoot him. The effort was futile.

In the stillness of the morning Heavy Runner’s sleeping camp was doomed. The soldiers were on its edge, ready for the kill. It would have been a perfect time to take prisoners, but that was not an option for Baker and his command.

Heavy Runner said “there was nothing to fear” and that “he would show the whites his ‘name paper.’” After all, they knew that Heavy Runner had met in peace with Gen. Sully on January 2 and been given a paper that he believed would protect him and his band from attack.

Heavy Runner handed the commanding officer “some papers, which the commanding officer read, then he tore them up and threw them away,” recalled Mountain Chief’s 29-year-old daughter, Good Bear Woman. She then saw Heavy Runner turn “about face” and the “soldiers fired upon him and killed him.” Kipp witnessed the same.

In the melee that followed the killing of Heavy Runner, the bullets started to come from everywhere: from Doane’s troops on the ground around the tipis and from the top of the bluffs above the Marias. A newspaper reported: “The work of slaughter continued for about three hours.”

Private William Birth, 21, and the rest of K Company of the mounted infantry from Fort Shaw came down the bluffs and dismounted. They had been thrown into the fray. As he and the others approached the village, he was close enough to observe the lodges and said that he was surprised that the Indians “did not fight when we came upon their camp.”

The Indians who Birth saw were all too sick or too frightened to fight and “only sticked their heads out of their tents and went and laid back and covered up again.” Without much hesitancy, Birth and the other infantrymen started firing into the tents. Even as the shots were being fired into the tipis, the Indians “still….would not return the fire.”

The soldiers around Birth became emboldened: unafraid of any kind of armed resistance by the Indians, they “went up to their tents and took…butcher knives and cut open their tents and shot them as they lay under their blankets and buffalo robes.” But that was not extreme enough: Birth and his companions “killed some with axes.”

What resistance the Indians mounted against the torrent of bullets was small. They fired only a few shots themselves, but one of them hit Pvt. Walter McKay of Thompson’s L Company, killing him instantly.

A newspaper attempted to portray the ghastly event: “The sounds of firearms; yells of the infuriated soldiers; yells and death-cries of the redskins; the barking and howling of the Indian dogs, all mingling, made the scene one of terrible interest. Anon, kegs of powder, carefully stowed away in several of the lodges, would explode and kill the inmates…. Several attempted to pass from one side of the river to the other, but the wide circles of red with Indians in the center, told but too well how vain was the attempt.”

A seven-year-old Piegan boy miraculously got away with his life, but not before his eyes witnessed the horror of young babies being “slung by their heels and heads bashed on rocks.” Terrified, he was able somehow to run from the camp in cold winter. He covered about 70 miles to safety near the Rocky Mountains, where he was taken in by a white family and adopted.

Heavy Runner’s camp was completely destroyed and became quiet. Most of the soldiers ceased their fire and prepared to go after Mountain Chief. Arriving at a place on the Marias where Mountain Chief was supposed to be, Baker found nothing but an empty camp. Prints in the snow showed the distressed Baker that “the Indians had scattered in every direction, that it was impossible to pursue them.”

Controversy Shunned

Many Eastern newspapers had become fully invested in the controversy, including the New York Evening Post: “We must express our absolute horror at the cold-blooded massacre of women and children—ninety women and fifty young children—perpetrated by the United States soldiers in Montana recently.”

On the other side of the controversy, the Bozeman Pick and Plow reported: “That the Indian of poetry and romance is not the Indian of fact: the former is said to be noble, magnanimous, faithful, and brave; the latter we know to be possessed of every attribute of beastly depravity and ferocity….”

The New York Times remarked that “the slaughter of the Piegans in Montana is a more serious and a more shocking affair than the sacking of Black Kettle’s camp on the Washita.” The paper noted that even Baker’s “rude estimate admits of the killing of no less than fifty-three women and children.” What incensed the Times most was Baker’s report of “140 women and children captured and released.” “Released to what?” the Times asked, and then answered: “To starvation and freezing to death.”

William Tecumseh Sherman, the U.S. Army’s top commander, dictated the way in which the history of the event should be written: “I prefer to believe that the majority of the killed at Mountain Chief’s camp were warriors; that the firing ceased the moment resistance was at an end; that quarter was given to all that asked for it; and that a hundred women and children were allowed to go free to join the other bands of the same tribe known to be camped near by, rather than the absurd report that there were only thirteen warriors killed, and that all the balance were women and children, more or less afflicted with small-pox.”

Something had set off Sherman. The House of Representatives had been considering a bill that would “transfer the control of Indian Affairs to the War Department,” which Sherman wanted. When John A. Logan, a congressman from Illinois and chair of the Committee on Military Affairs, “read the account of the Piegan massacre his blood ran cold in his veins, and he…asked the committee to…let the Indian Bureau remain where it is, and the committee had agreed to that.”

This had obviously upset Sherman enough to send out a warning that there would be trouble for anyone in the Army who contested the number, age and sex of the Piegans killed on the Marias. As part of his public relations fight, Sherman told Sheridan on March 28 to “assure Colonel Baker that no amount of clamor has shaken our confidence in him.”

Until March 26, the editors of the Army and Navy Journal had printed accounts of the massacre that came to them from other newspapers. They now stood up and took an editorial stance on the massacre, strongly in favor of the Army. The Journal lauded Baker’s performance, reporting: “Colonel Baker’s report of his scout against the hostile Piegan and Blood Indians shows incontestably that the march itself was a heroic one…and we agree with Colonel Baker that ‘too much credit cannot be given to the officers and men of the command for their conduct during the whole expedition.’”

Success was, of course, far from true, because Baker had struck the wrong band, killing their chief Heavy Runner, and was not able to attack Mountain Chief’s band.

Hallowed Ground

On January 23, for a few years now, some faculty members and students from the Blackfeet Community College have gathered annually on the bluffs overlooking a spot on the Marias River in Montana known as the Big Bend. They come mostly from Browning on the Blackfeet Reservation in northwest Montana, just on the east side of Glacier National Park. Most of them are members of the historic Piegan tribe, now known as the Blackfeet. As the group gathers in a circle to the sound of Indian drumming and singing, a 21-shot salute is fired in honor of the 217 Piegans massacred on that day in 1870.

All historical 19th-century conflicts in the Montana Territory between the Indians and the U.S. Army have been overshadowed by George Custer’s battle on the Little Bighorn in 1876. Perhaps that is because the site was preserved early to mark the graves of U.S. soldiers and later became a national monument to which thousands flock every year.

Today, nearly 150 years after the Baker Massacre on the Marias, no monument or sign marks the exact location, with not even a passable road to get there. No physical element keeps it in people’s minds. That may be best, as this hallowed ground is a sacred place to the Blackfeet.

– Courtesy Overholser Historical Research Center, Fort Benton, Montana –