– Photography By Gary Johnson –

Sometimes at night, the howling wind would commence to blow. For shelter, we pulled canvas bed tarps over our heads.

Sitting around the campfire, we scraped sand off our steaks before taking a bite. One night, a gust lifted our dinner table skyward and dumped our meal on the gritty ground.

When we retired for bed, we crawled as deep as we could into our soogans, then awoke in the morning, spitting sand. We were livin’ high style, sleeping on cots in tents.

I was in Monument Valley again, sharing a small canvas tent with Ben Johnson, a far cry from our early days in the valley of the rocks near the Arizona-Utah border when we slept on the ground at the foot of a towering butte up near Susie Yazzie’s hogan.

During the spring of 1996, Arizona Highways Magazine Editor Bob Early had asked photographer Gary Johnson and I to join Don Donnelly’s trail riding outfit in Monument Valley to report a story about Ben. The legendary cowboy actor was making a sentimental journey to the place where Hollywood Director John Ford had “discovered” him, while filming one of his “Cavalry Triads,” 1948’s Fort Apache.

I had ridden as a horseback historian in Donnelly’s trail rides for about 10 years, starting in the 1980s. I talked history during the day and sung classic cowboy songs around the campfire at night. We toured spectacular scenic places: Canyon de Chelly, the Bradshaw, Chiricahua and San Francisco mountains, the Mogollon Rim and, of course, Monument Valley.

Path to Hollywood

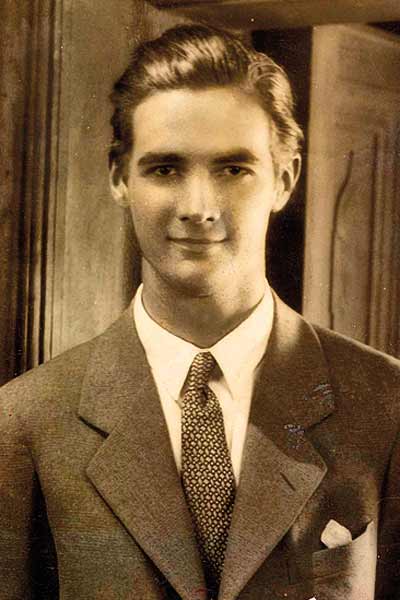

Howard Hughes is credited with bringing Ben out to California from Oklahoma in the late 1930s. Hughes had bought some horses from an Oklahoma ranch where Ben worked and liked the way he handled horses. The movie director offered him a job in Hollywood, bringing horses to northern Arizona, where Hughes was filming The Outlaw starring Jane Russell. Ben’s weekly wages went from $40 to $175. “It didn’t take me long to figure out this was a good deal,” he told me on his last trail ride.

When the filming was finished, Ben found work in the movies. During the early 1940s, he wrangled and performed stunt doubling for John Wayne, James Stewart, Joel McCrea and Gary Cooper. Hughes introduced Ben to Director John Ford who hired the horseman to perform stunt work and double in 1948 for Henry Fonda in Fort Apache. As they say, “The rest is history.”

While filming the movie, a team of horses pulling a wagon spooked and stampeded with three actors on board. Ben, seeing an accident in the making, rode after the team and, just like in the movies, he grabbed the halter on the lead horse, saving the actors from serious injury or worse. A grateful Ford promised him more work.

“I thought maybe he might give me a speaking part in his next film,” Ben said. “He invited me into his office one day and told me to sit down, then he handed me a piece of paper. I read down to about the third line and saw ‘$5,000 a week.’ I stopped reading, grabbed a pen and signed it.”

“I didn’t even ask what I had to do,” he said with a grin.

Ben went on to become one of Hollywood’s most popular actors, playing everything from a devil-may-care cowboy, bad man and gunman to curmudgeon and old-timer. He was one of the all-time great horsemen in the business. To see him glide into the saddle in those films was poetry in motion. When complimented on his riding skills, Ben modestly replied, “I wasn’t a good actor, so I had to be able to do something.”

One of the actor’s best roles was his Oscar-winning performance as “Sam the Lion,” the owner of a pool hall in a small Texas town in 1971’s The Last Picture Show. He didn’t ride a horse in that one. He stole the show at the Oscars when he raised his award in his hand, grinned and said, “This couldn’t have happened to a nicer fellow!”

His Western persona and skills as a horseman brought authenticity to his roles. He liked to say, “I make a lot of money in the movies playing Ben Johnson.”

He was pretty much like those characters he played in some 300 movies. Ford’s last words to him were: “Ben, don’t forget to stay real.”

He didn’t cotton to the excessive use of profanity that became popular during the 1960s. In fact, he turned down the role of “Sam the Lion” until Director Peter Bogdanovich expunged all the four-letter words in his lines. “I don’t have to say four-letter words around women and kids to make myself a name,” he said.

One evening, we were sitting around the campfire as the wind kicked up sand and a light rain began to fall from the dark clouds hanging over Monument Valley. Ben was sharing the story behind his famous barroom fight with Alan Ladd in 1953’s Shane. Ben was six-foot-two next to Ladd’s five-foot-five frame. Ben’s character had to lose the fight, but the actors had to make that look realistic for audiences.

“He could walk under my outstretched arm,” said Ben, as his weathered face broke into a big smile, “so they put him on a platform and had me stand in a hole.”

The Great Leap

In Monument Valley, Ben reminisced about an experience he had while working in 1950’s Wagon Master. He was being pursued by a band of Navajo warriors.

“I rode to this bluff and was supposed to turn and ride along the ridge, but the horse I was on got a case of cold jaw and wouldn’t respond to the bit,” Ben said. “He jumped off that bluff, and we landed in sand up to his belly. The reins were lying in the sand, so I picked ’em up, spurred him and off we went.”

That unintended leap was later measured at 32 feet. His scene came to be known as one of the greatest examples of horsemanship ever filmed.

Ben could always handle the unexpected and make a scene work. That was why he was one of Ford’s favorites.

One afternoon, Ben pointed toward the twin buttes called the Mittens. “We were filming She Wore a Yellow Ribbon when a big thunderstorm rolled in,” he said. “Lightning was bouncing off those buttes, so the assistant director told the actors and crew to pack it in. Mr. Ford liked to of had a fit. ‘I’ll tell you when to cut,’ he bellowed.

“We were pretty scared of the lightning, but we were more scared of John Ford, so we kept shooting.”

Thanks in part to that scene in the lightning storm, the film won an Oscar for cinematography in 1949.

Over the next 40 years, Ben would star or appear in hundreds of films and television shows, mostly Westerns. He took a break from the movies in 1953 to rodeo. He won the PRCA World Team Roping Championship and, in 1973, was inducted into the Pro Rodeo Hall of Fame.

He is the only movie star to win a World Championship rodeo buckle and an Academy Award. In 1982, he was inducted into the Western Performers Hall of Fame at the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City. Twelve years later, he earned a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

On the last day of our trail ride, Donnelly staged a small rodeo with no rough stock, just events that included balancing an egg on a spoon at a gallop and barrel racing.

I came in second place in the barrel race; Ben finished first. I was the proudest second-place finisher you ever saw!

Near the horse corral, six-year-old Bronco Grinstead was trying to rope a rubber steer’s head sticking out of a bale of hay and had trouble getting his loop to fall over the horns. Ben took the rope and offered him a few tips. Bronco wasn’t aware he was getting advice from a former world champion. His folks later told him when he was old enough to understand. Ben built a loop, then noticed a number of us had gathered to watch.

He grinned sheepishly and said, “Boy, I’d better not miss!”

He didn’t, and Bronco was noticeably impressed, more than all that movie star stuff he had been hearing about all week.

A Friend to Miss

On April 8, 1996, I was rolling down the highway in my Ford 150 Pickup when the news came over the radio that Ben had died, a couple months shy of turning 78. The news hit me like the kick of a mule.

Just a few weeks earlier, I was sitting with Ben and actor Harry Carey Jr. on a panel at the Festival of the West in Scottsdale, Arizona, answering questions. I was way out of my league that day and smart enough to sit there like a bump on a log and let them do most of the talking.

My friendship with Ben had developed over the years, since I first met him around 1980, at the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. Now the great man had left us. Like millions of others, I felt I had lost a good friend. He affected a lot of folks that way.

Fittingly, Ben had taken his last earthly ride in Monument Valley—where it all began.

A few days after Ben died, Arizona songwriter Ted Newman and I sat down and wrote a tribute to our friend, “Ben Johnson Evening Star,” that Arizona Cowboy Magazine later published:

There’s a brand new star in the evening sky, and it shines all over the land. Bringing memories dear of a star here on earth of a cowboy—ever so grand.

The stuff of real heros, bigger than life, with simple values so plain. Honesty, realism and always respect. The likes we’ll not soon see again.

Ben Johnson, an honest name for a man of decency, honor and pride. The man on the screen was the man in real life, bringing balance to life’s ride.

He didn’t play cowboy. He was what you saw. He was down home and cowboy clean through. He could rope, he could ride and compete with the best. Everything that he did was all true.

He knew about horses. He knew how to ride. He could take a cayuse any place. Seein’ him in the saddle was like equine ballet—an expression of horse-ridin’ grace.

“I wasn’t much of an actor,” he’d say. Then he’d smile with that big, easy grin. And he’d add with a twinkle in his wrinkled eyes, “But, I could play the hell out of Old Ben.”

World champ as a cowboy with a buckle of gold. He won an Oscar in ’72. He wasn’t a cowboy in The Last Picture Show. As an actor, he was mighty good too.

I’d seen him in the movies since I was a kid. I grew up with his face in my mind. This cowboy of cowboys, this man among men, who was tough, honest, caring and kind.

He and his wife had no kids of their own, but he helped kids again and again. And for folks from all over, both common and rich, he was lovingly called Uncle Ben.

The things he stood for, and the life that he lived, are remembered with love, near and far. And it might be less painful to know deep inside that in heaven there’s a new evening star.

– Courtesy RKO Radio Pictures –

– True West Archives –

– True West Archives –

Marshall Trimble is Arizona’s official state historian, board president of the Arizona Historical Society and vice president of the Wild West History Association. He has taught Arizona history at Scottsdale Community College for 40 years and written more than 20 books on Arizona and the West.