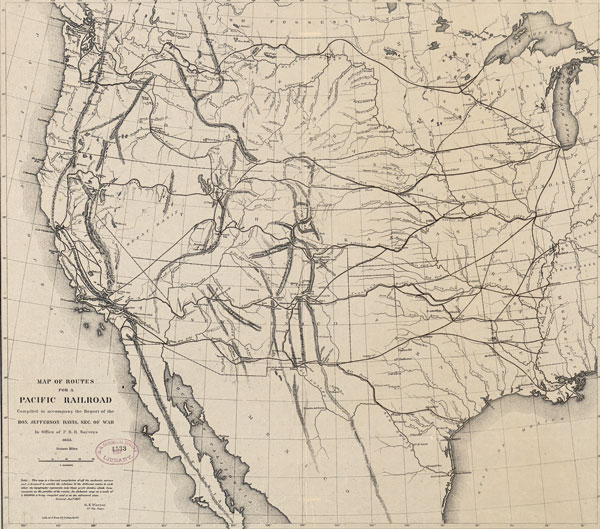

In March 1853, Congress appropriated funding for four surveys of potential railroad routes throughout the American West. The surveys constitute one of the most impressive feats of geographical science in 19th-century America. The reports also contained one of the first detailed maps of the entire West, Lt. Gouverneur Kemble Warren’s “Map of the Territory of the United States from the Mississippi to the Pacific Ocean.”

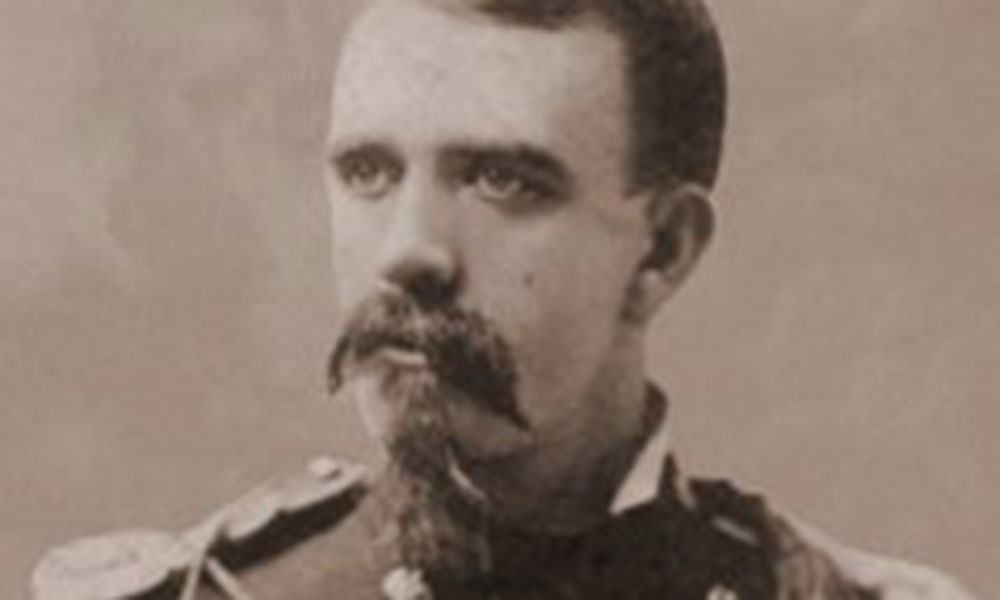

Upon graduating from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in 1850, Warren joined the Corps of Topographical Engineers. He conducted most of his work in 1854, which allowed him to benefit from the extensive reconnaissance knowledge gained from the railroad surveys, as well as his own expeditions through Dakota Territory. The cartographer reconciled conflicting accounts and synthesized disparate geographical information into a single comprehensive view.

Warren took pains to list the dozens of “authorities” who revealed the topography of the West over time, beginning his list with Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, the first agents of the new nation in the American West, rather than with Aaron Arrowsmith, whose British map of the West was the most reliable to that point. Warren’s map was a history of official geographical knowledge undertaken in the field, making his map unprecedented.

Yet for all his attention to the genealogy of exploration, Warren downplayed American Indian knowledge, even when his “authorities” relied on it. Such practice was typical. The map of the Missouri Basin that Arrowsmith created incorporated uncredited details drawn by Blackfoot Chief Ackomokki.

Between 1869 and 1879, the federal government mounted more surveys of its Western lands, undertaken by Clarence King, John Wesley Powell, Ferdinand Hayden and George Wheeler. The latter was so taken with the history of mapping that he reprinted Warren’s memoir from the 1850s. Warren and Wheeler’s reports were a crash course in discovery and exploration through maps, a territorial inventory of American history. Prior to 1850, this awareness of past geographical knowledge as relevant to the nation’s future did not exist.

During the Civil War, Warren created battle maps, particularly of the Gettysburg campaign. Initially a lieutenant colonel for the Union, Warren had risen to the rank of major general after his heroic efforts during Gettysburg. As chief engineer, he initiated a last-minute defense of Little Round Top that rescued an undefended left flank of the Union Army from certain attack by Confederates. He came into conflict with Philip Sheridan when the major general humiliated Warren by removing him from command in 1865.

After the war, Warren engaged in civil engineering projects. He fought to clear his name with the military and was exonerated from any wrongdoing in 1882, the year he died, at the age of 52.

Susan Schulten, professor of history at the University of Denver, is the author of Mapping the Nation: History and Cartography in Nineteenth-Century America. This is an edited excerpt from her book.