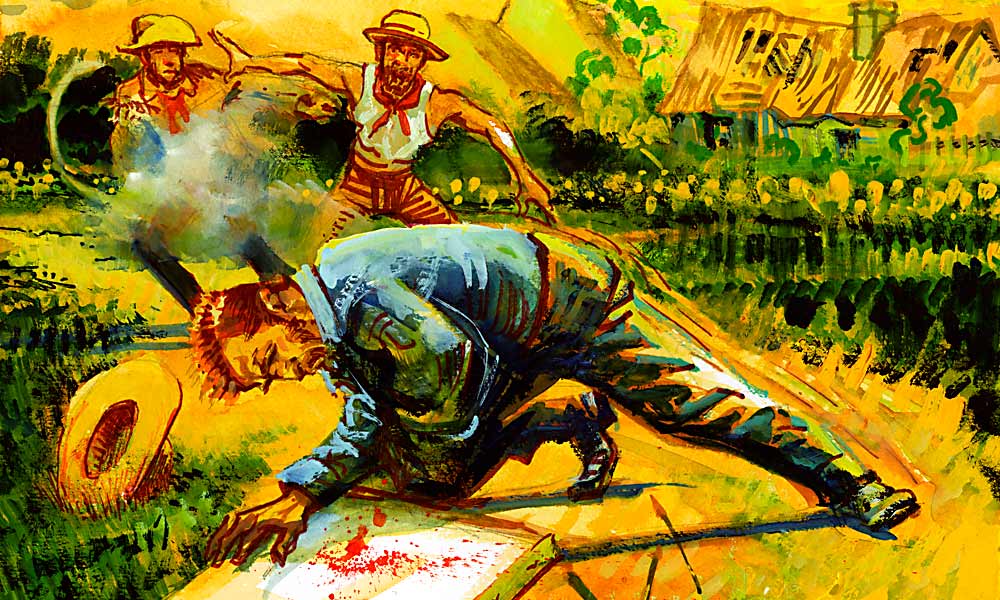

Vincent van Gogh is shot west of Auvers-sur-Oise, somewhere on the road to Chaponval, by René Secrétan, a Buffalo Bill Cody wannabe who brandishes a pistol that goes off, probably by accident. Many now believe Vincent literally took the bullet for the boys and martyred himself. He says a telling thing to his brother Theo before he dies, “Do not cry. I did it for the good of everybody.”

– All Illustrations by Bob Boze Bell unless otherwise noted –

July 27, 1890

Vincent van Gogh finishes his noontime meal at the Ravoux Inn, and heads for the wheatfields northeast of the tiny hamlet of Auvers-sur-Oise, 20 miles north of Paris, France.

He is carrying an easel, canvas, paints, brushes and sketchbooks, along with a pistol he has borrowed from innkeeper Arthur Ravoux, supposedly to ward off a murder of crows that have been bothering the artist. With a history of mental instability, Vincent is especially distraught today, over the news of his younger brother Theo’s ill health and financial setbacks.

Unable to paint, Vincent lays his easel against a haystack. He retrieves the pistol and shoots himself under the heart.

The blow knocks out Vincent, but doesn’t kill him. He awakens in the evening darkness. When he can’t find the gun to finish himself off, he stumbles down the hillside and returns to the Ravoux Inn, where he goes to his room and lingers, dying 30 hours later.

This has been the standard narrative for nearly 130 years, but recent scholarship has cast doubts upon this version of the artist’s death. A more likely version is this:

After his noontime meal at Ravoux Inn, Vincent heads west on the main road toward the Chaponval train station. Somewhere on this road, Vincent encounters the Secrétan brothers, René and Gaston. René taunts the Dutch painter with his pistol and the gun goes off, striking Vincent in the side. Vincent stumbles back to the inn and tells everyone he bungled his suicide.

When Theo arrives the next day from Paris, he finds Vincent sitting up in bed, smoking his pipe. Incredibly, Vincent survives the gunshot wound for two days before he dies.

After a short ceremony at the Ravoux Inn, Vincent is buried in the hillside cemetery (see map below). The local curate will not permit a funeral service at the church in Auvers because of the specter of suicide. The abbot even forbids the use of the parish hearse.

Dueling Death Sites

After Vincent’s death, most reports have the shooting taking place west of town near the Château d’Auvers. This is where author Irving Stone places the event in his classic novelization of the artist’s life, Lust for Life. But somewhere along the line, the location of the death site shifted to the wheatfields northeast of the village, perhaps due, in part, because modern-day tour guides can kill two crows with one stone: show tourists the alleged location of Wheatfield with Crows (the inference being that the artist shot himself after painting his obituary) and walk another 50 yards to the cemetery where Vincent and Theo are buried. Saves on shoe leather.

The Paris Punk

René Secrétan is the 16-year-old son of a prominent pharmacist from Paris, France. His wealthy father owns a holiday house in the Auvers-sur-Oise area, and every June, the family decamps to the estate for the fishing season. René’s older brother, Gaston, an aspiring 19-year-old artist, strikes up an acquaintance with Vincent to discuss art. René cannot stand the “fou roux” (red-headed madman). He fully expects the authorities to come at any moment to haul the Dutchman away “because of his hare-brained ideas and the way he lived,” René later recounts.

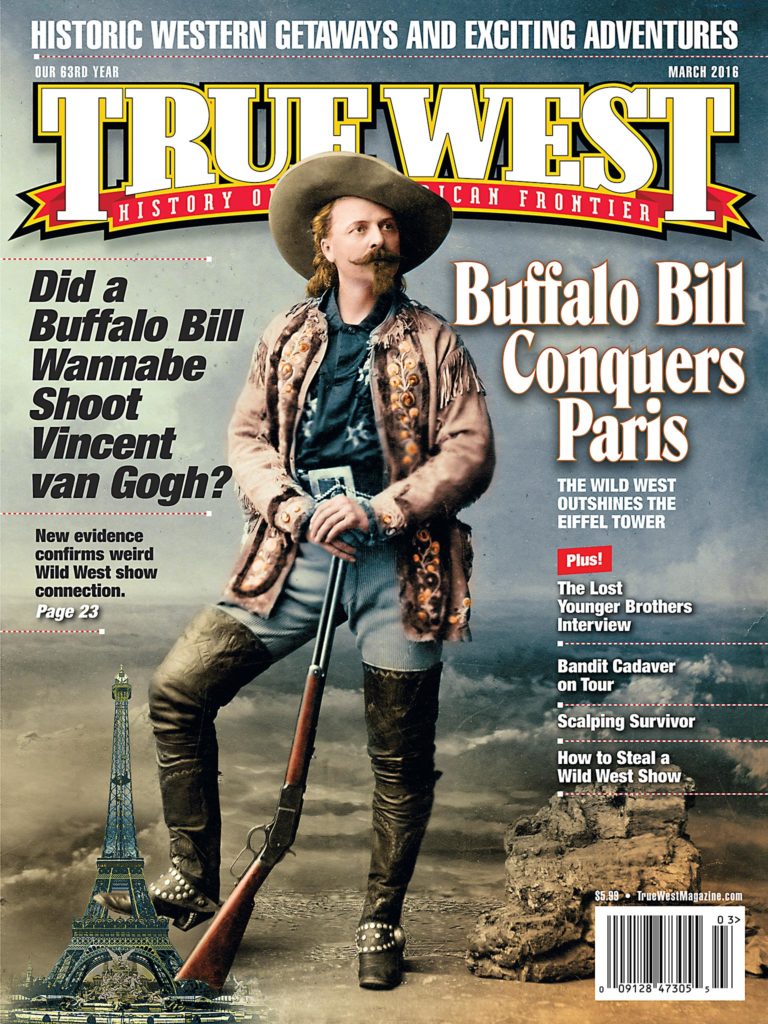

Vincent nicknames René “Buffalo Bill” because of the costume he began wearing after seeing William “Buffalo Bill” Cody’s Wild West show at the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris. Going all out, René wore boots, a fringed coat and a cowboy hat, with the front pushed up, to emulate his new hero. Vincent mispronounces René’s nickname as “Puffalo Pill,” which only infuriates the Paris punk to greater efforts of abuse.

René and his gang—Summer Boys—love to torment Vincent by putting salt in his coffee. They also hide a grass snake in his paint box, and when the Dutchman discovers it, he almost blacks out. René notices Vincent sometimes sucks on a dry paintbrush while he thinks, so the gang rubs the brush with chili pepper and watches with glee when the artist hops around in pain from their trick.

Being the wealthy son of a Paris businessman provides high-end perks: the Secrétan boys often import showgirls—cantiniéres—from the Moulin Rouge. When the boys kiss and fondle the girls, Vincent “modestly [looks] the other way,” René recalls, a reaction that “seemed madly funny to our little chicks.” René encourages the girls to “provoke [Vincent] with their amorous attentions,” but the artist remains firm in his resolve.

None of this would have been known if not for Kirk Douglas. The Academy Award-winning movie Lust for Life, starring Douglas, is released in 1956. When 82-year-old René sees the movie, he is furious. He gives two interviews, attempting to discredit Douglas’s flattering portrayal of Vincent. In the process, he gives historians a reasonable suspicion that René, in fact, fired the fatal bullet that took Vincent’s life.

“Too Far Out”

More than one version of the Vincent van Gogh shooting states the artist shot himself “in the chest,” but Dr. Paul Gachet reported the bullet entered the abdomen just “below the ribs.” That is not a chest wound, and the finding supports the theory that Vincent was shot in an accidental way by someone else. Who shoots themselves in the side?

The police report stated that the shot was fired “too far out” for Vincent to have pulled the trigger.

With those two reports, historians have a strong case—at least anecdotally—that the Buffalo Bill wannabe shot Vincent.

Vincent did feel trapped. His brother Theo was suffering from reversals at work, and Theo’s newborn son (named for Vincent) was sickly. Concerned that he, too, was a drain on his brother, who helped fund his artist lifestyle, Vincent must have thought to himself, “What can I do to help?”

Exactly a year before, in July 1889, a painting by Vincent’s hero Jean-François Millet had sold for a record amount—a half-million francs—nearly 15 years after Millet’s death. It’s an old saw, but a fact of life in the art world: dead artists sell better than live ones.

Armed with this knowledge, Vincent hiked up the hill west of town, along the perimeter fence of the Château d’Auvers. Someone fired a pistol that hit him in the side.

In our collective dreams, Vincent must commit suicide. After all, his suicide gave him his place in the world.

Or, as art critic John Perreault put it, “We need closure. We need the myth of the crazy, tormented, self-destructive artist to convince us that painters, poets, and musicians are all nuts, so their larger-than-life lives can continue to offer escapism from the bourgeois armchair of our own lack of freedom. And also, paradoxically, make us feel relieved we are not artists. In our dreams, van Gogh must commit suicide, otherwise the story doesn’t have legs.”

Still, the most compelling quote we have about Vincent’s final hours is his own: “Do not cry. I did it for the good of everybody.” Vincent said these words, knowing his death would relieve his brother Theo of the strain of financial support and also that his statement would save two boys from a charge of manslaughter.

Aftermath: Odds & Ends

Dr. Jean Mazery, the first physician attending to Vincent, commented on the wound just below the ribs as being “about the size of a large pea” and bleeding only a trickle. The police came the next day. When the artist was advised suicide is a crime, he replied, “Do not accuse anyone. It is I who wanted to kill myself.”

Theo van Gogh, 33, died six months after Vincent, in 1891. First buried in Utrecht, Netherlands, his body was dug up in 1914 under orders from his wife, Johanna, and moved to Auvers-sur-Oise, France, to rest beside his brother.

Renowned art historian John Rewald interviewed locals in the 1930s who told him that “young boys shot Vincent accidentally.” The boys “were reluctant to speak up for fear of being accused of murder and that Van Gogh decided to protect them and to be a martyr.”

Based on Irving Stone’s best-selling novelization of Vincent’s life, the movie version of Lust for Life was released in 1956 and cemented the artist’s growing celebrity. This upset 82-year-old René Secrétan, who gave a series of interviews to Victor Doiteau, a French writer. Seen by many as a deathbed confession, René admitted the gun was his. In the 1950s, a farmer discovered the pistol while plowing in the vicinity of the Château d’Auvers.

Recommended: Van Gogh: The Life by Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith, published by Random House.