In 1833, the Bent brothers—Charles and William—along with partner Ceran St. Vrain were building a trading empire in the Southwest. The plan: to operate mercantile stores and trading posts in what is now Colorado and New Mexico.

William Bent was tasked with finding a central post location, one between their company store in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and their hometown and merchandise suppliers in St. Louis, Missouri. He sought advice from Cheyenne Chief Yellow Wolf, who recommended a place called Big Timbers (modern southeast Colorado, near the Kansas border).

What did William decide to do? He located the place some 40 miles west of that spot. Typical white guy, not listening to the natives.

In time, the adobe structure William built became known as Bent’s Fort, a major frontier post, located out in the middle of nowhere. “Why he chose this spot over the other, we have no idea,” says Greg Holt, park ranger/interpreter at Bent’s Old Fort National Historic Site.

Maybe that decision was based on the relatively close proximity of the mountains and the mountain man trade. Or because it was close to the Indians, another trading partner. Or because it was located near the Santa Fe Trail, heading south to Santa Fe. Or all of the above.

For its time, Bent’s Fort was quite the place. The 137 feet-by-178 feet building had walls 14 feet high and 30 inches thick. The post contained carpenter and blacksmith shops, trading rooms, a council room, billiard room, warehouses, a large dining room, trappers’ and hunters’ quarters, laborers’ quarters, as well as accommo-dations for the resident physician and for the owners and their families.

The fort had a strong run for more than 15 years. But by 1849, the place had been abandoned. Cholera decimated the Indians; the survivors moved away. The days of the mountain man beaver trade were pretty much finished. Overgrazing had driven away the buffalo. William Bent’s brother and partner Charles—serving as New Mexico Territorial governor—was killed in the Taos Revolt of 1847. And his other partner St. Vrain wanted to bail out of the business.

Ranger Holt says the Bent brothers did not do a good job of upkeep: “The archaeology studies showed there were beam pockets in the middle of the rooms, and that suggests the idea that the walls were caving in a bit.”

William finally listened to Yellow Wolf—who by 1849 was his father-in-law—and moved most of his operation to Big Timbers to build Bent’s New Fort. Several reports indicated that he burned the old structure as he was leaving.

For some years, the “old” location was used as a stagecoach stop. Yet for many folks, Bent’s Old Fort became a distant memory—especially when the stage line from Denver, Colorado, to Santa Fe, New Mexico, bypassed the fort.

Flash ahead to the 1920s. Colorado entrepreneur A.E. Reynolds donates land containing the fort ruins to the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR), who began floating the idea of reconstructing the old fort. Nothing came of that proposal for some 30 years.

In 1954, the state of Colorado owned the spot. Archaeological digs identified the location of the fort walls, and some adobe bricks were actually laid as part of a reconstruction effort. Yet state officials believed the feds could do a better job on the project, and they pushed for Washington, D.C. to take over. That happened in June of 1960, when President Dwight Eisenhower signed a measure making Bent’s Old Fort a National Historic Site.

In 1976, two years after work started, the accurately reconstructed fort was dedicated. In recent years, some 25,000 visitors tour the site each year.

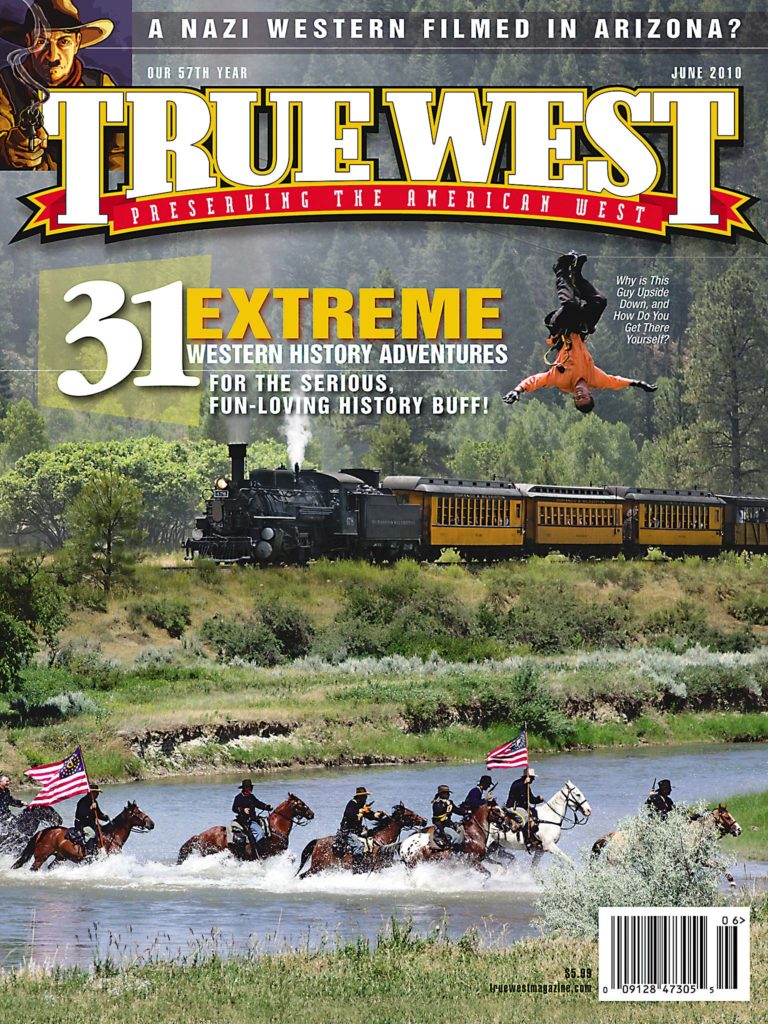

The numbers may well be up this June 4-5. That’s because Bent’s Old Fort is celebrating the 50th anniversary of its inclusion as a National Historic Site. Ranger Holt is in charge of the event, which will feature a fandango, a trail ride of 1830s trappers and hunters, a re-enactment of the 1912 DAR marker dedication and a presentation of Hollywood films made at the site.

Among the special guests: some direct descendants of William Bent himself, the man who built and later burned the fort. History, as it so often does, will come full circle.