– All Images Courtesy Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument Archives, NPS.gov Unless Otherwise Noted –

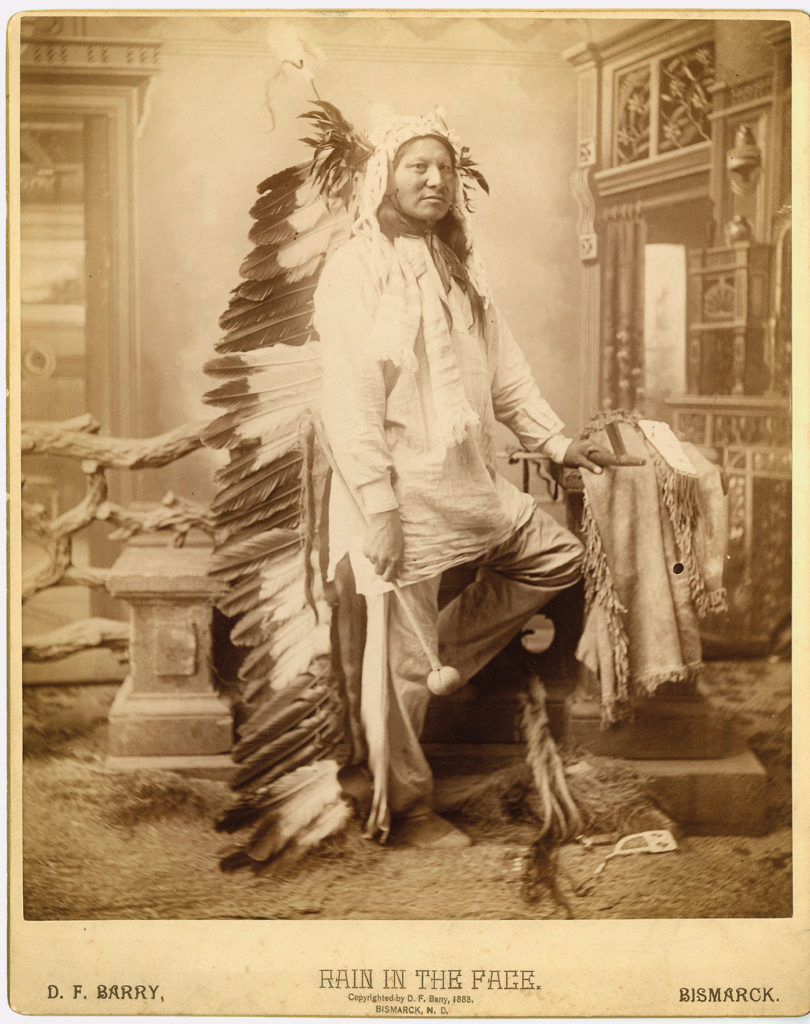

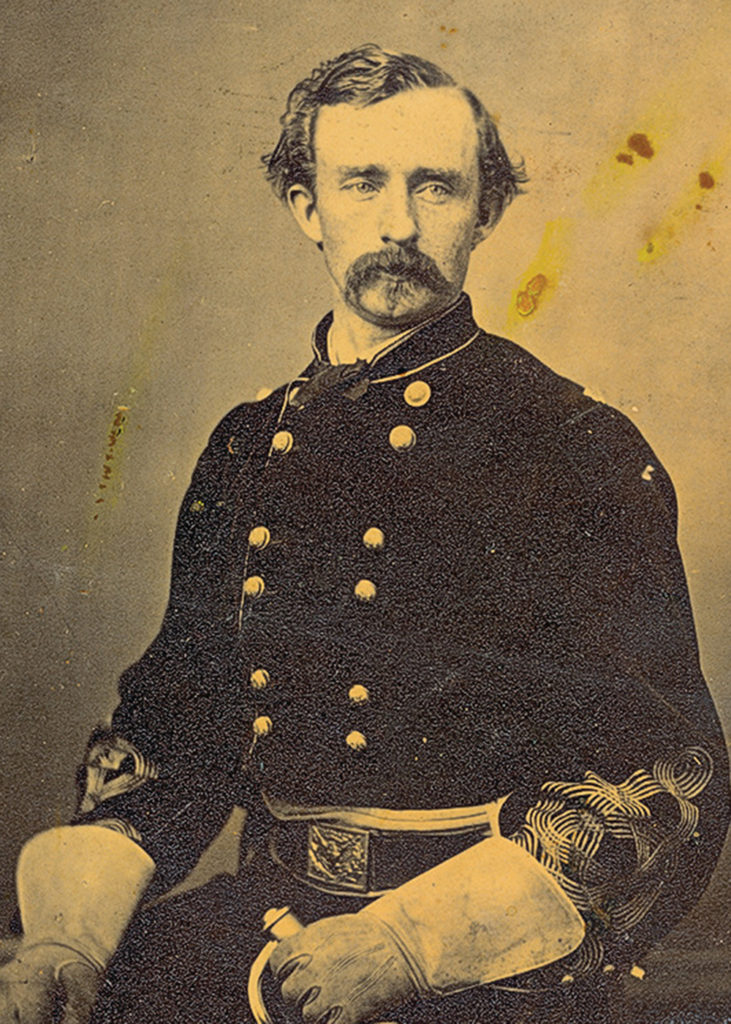

By the early afternoon of June 25, 1876, Rain-in-the-Face had become a Hunkpapa band leader with more than 100 followers. The story of his having been taken prisoner and escaping the clutches of the 7th Cavalry and Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer, Phehín HánskA (Long Hair), on April 18, 1875, after four months of captivity at Fort Lincoln, Dakota Territory, had spread throughout the Lakota tribes. His bravery had paid off and as he had once looked to Sitting Bull for leadership and inspiration, younger warriors now looked to him for the same. A week earlier he had participated in the Battle of the Rosebud on June 17, in which Crazy Horse had led over 1,500 Lakota and Northern Cheyenne warriors to victory against Brig. Gen. George Crook and his 1,000 troopers, successfully halting Crook’s advance. “I think he was more wise than brave,” Rain-in-the-Face would later comment about Crook, whom the Lakota called Three Stars.

Rain-in-the-Face and his band were now encamped along the Little Bighorn River in southern Montana with around 10,000 Lakota, Cheyenne and Arapaho, including around 2,000 fighting men. The enormous camp stretched on for three miles. Sitting Bull had held a Sundance earlier in the month, in which he had a vision of white soldiers falling upside down into their village like grasshoppers. Rain-in-the-Face was eating a meal at a war council when the cry first went up of soldiers approaching the village. It was Custer and his 7th Cavalry, having disregarded warnings from his Crow scouts about the size of the Indian encampment.

Custer had sent Maj. Marcus Reno and three companies to attack the village from the southeast. Captain Frederick Benteen and three companies would lead a reconnaissance sweep to the southwest. Custer himself would lead five companies northwest over the hills along the river and attack the camp from the northeast.

Rain-in-the-Face took some time getting back to his own lodge and ready himself for the approaching battle. By the time he emerged ready to fight, Major Reno and his three companies had been driven back across the river and up to what became known as Reno Hill, losing over 40 troopers along the way.

Word soon spread among the village that another group of Bluecoats (Custer and five companies) were approaching the camp from the bluffs across the river about two miles upstream. Hundreds of warriors rode back from Reno Hill and from the Indian encampment to meet this new threat. Rain-in-the-Face fell in with them and joined the fighting. He soon spotted a young Hunkpapa woman named Moving Robe among them. “Behold, there is among us a young woman! Let no young man hide behind her garment!” the war leader recalled shouting. “I knew that would make those young men brave.”

Hundreds of warriors swarmed to meet Custer and his companies, who soon became overwhelmed and driven back up the bluffs. Gall, a Lakota battle leader, overcome with grief that two of his wives and three of his children were killed during the Reno attack, came screaming up the bluffs with a hatchet in hand like a madman. After helping to drive back Reno’s three columns, Crazy Horse turned back and rode northwest along the Little Bighorn River before leading his warriors in a brilliant tactical sweep up the Deep Coulee and emerging behind Custer and his companies, cutting off any chance of escape.

War-whoops and Lakota cries of “Hókahé!”(Let’s go!) and “Nakénuŋla waúŋ weló!”(It is a good day to die!) carried through the dust clouds that rose over the battlefield. The cavalrymen offered what resistance they could against the 2,000 warriors until a final charge led by Crazy Horse broke what was left of their skirmish lines. Some of the desperate soldiers bravely stood firm and continued fighting until they were cut down. Several committed suicide, shooting themselves in the head. The remaining cavalrymen desperately fled for their lives in several directions, as the battle disintegrated into the equivalent of a buffalo hunt with the Indians riding down the fleeing troopers and dispatching them.

Custer and his entire five companies, numbering 210 men, including his younger brother, Capt. Thomas W. Custer, had been decimated. The Lakota, Northern Cheyenne and Arapaho had won their greatest victory against the United States Army.

A Legend False and Unclaimed

The story that Rain-in-the-Face had cut out and eaten Capt. Tom Custer’s heart soon arose after the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Various testimony showed this was nothing more than a myth built up around a warrior so feared by his enemies. On June 28, three days after the battle, Lt. Edward S. Godfrey helped bury the mutilated bodies of his fellow cavalrymen on the battlefield. Godfrey later recalled: “[Tom Custer’s] body was lying face downward, all the scalp was removed, leaving only tufts of his fair hair on the nape of his neck. The skull was smashed in and a number of arrows had been shot into the back of the head and the body. We rolled the body over; the features where they had touched the ground were pressed out of shape and were somewhat decomposed. In turning the body, one arm which had been shot and broken, remained under his body; this was pulled out and on it we saw “T.W.C” and the goddess of liberty and flag. This, of course, completed our identification. His belly had been cut open and his entrails protruded. No examination was made to determine if his vitals had been removed.”

The scalping, skull smashing and cutting open of the abdomen were to be expected. The Lakotas commonly engaged in such treatment of an enemy’s dead body. Had Tom Custer’s heart been cut out, however, it would easily have been noticeable to Lt. Godfrey, who made no mention of any such mutilation to Tom’s chest cavity and unlikely would have spared such particular detail had it occurred.

Captain Frederick Benteen, who observed Tom Custer’s body later wrote, “The facts are that Tom Custer’s heart was not cut out at all. I am able to substantiate this by affidavit.” Dr. Henry R. Porter, the only surgeon to survive the battle also examined Tom’s mutilated body and later stated that his “heart was not cut out, as has been reported.” When asked if Rain-in-the-Face had cut out the heart of a soldier, Kill Eagle, a chief of the Sihasapa (Blackfeet) Lakota tribe, who were camped with the Hunkpapa at the Little Bighorn, said, “Rain was with me, he did not do it.”

A few months before his death, Rain-in-the-Face himself would declare: “Many lies have been told about me. Some say I killed the chief [George Custer], and others that I cut out the heart of his brother [Tom Custer], because he caused me to be imprisoned. After the battle we young men were chasing horses all over the prairie, while the old men and women plundered the bodies; if any mutilating was done, it was by the old men.”

Tom Custer’s heart was neither cut out nor eaten by Rain-in-the-Face, who probably never even approached his dead body. He was likely too busy tending to a wound he had suffered during the battle. Having ridden over a prostrate cavalryman, the wrongly presumed dead soldier had fired his revolver upwards into Rain-in-the-Face’s right thigh, the bullet scraping off four inches of flesh in a diagonal line. Some said Rain-in-the-Face tended his wound by taking a razor from a dead soldier and performing a primitive form of surgery on himself.

Over the years following the battle, many Indians were credited with killing Lt. Col George A. Custer that fateful afternoon. Rain-in-the-Face was not only among those credited, but at the top of the list. Attempting to determine exactly who killed George Custer is a futile endeavor, however the chance that it was Rain-in-the-Face is minimal.

Nearly 41 years of age at the time of the battle, Rain-in-the-Face was not expected to participate in the actual fighting. While he proudly laid claim to having killed a couple of soldiers on horseback with his war club and having taken their scalps, Rain-in-the-Face’s vivid account of the battle indicates he was more an active observer that day than a prominent participant. The Sioux warrior probably never came close enough to the front lines of battle to have been the one who killed Phehín HánskA, later declaring, “no one knows who killed the Long-Haired Chief. Why, in that fight the excitement was so great that we could scarcely recognize our nearest friends! Everything was done like lightning.”

Yet through a torrent of newspaper reports, Henry Longfellow’s grandiose poem “The Revenge of Rain-in-the-Face” and Elizabeth Custer’s inequitable writings, Rain-in-the-Face’s reputation for having both cut out and devoured Tom Custer’s heart and personally killed George Custer stood firm in many whites’ minds for decades. After all, it made an absorbing tale of frontier vengeance and savagery.

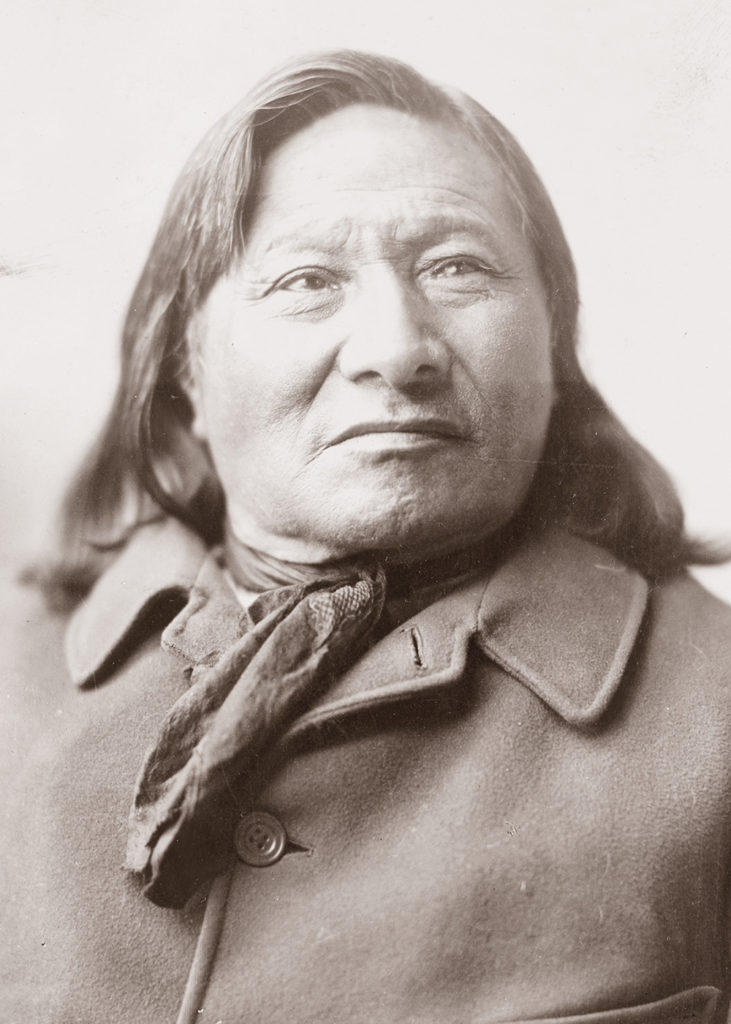

– Photo by Frank Bennett Fiske, Courtesy Library of Congress –

On May 21, 1905 the Los Angeles Herald printed an article about the melancholy old warrior which included several pictographs depicting moments from his life. It also read, “the blood is unchanged and the fire in his eye kindles now when he speaks of the wrongs of his people, and although seemingly friendly, he is, and always will be, an enemy of the white.”

His blood may have remained unchanged, but Rain-in-the-Face had recently converted to Christianity. Having overseen his surrender some 25 years earlier, Eli L. Huggins would later ask, “Which Rain-in-the-Face is the more interesting animal, the savage of the Little Bighorn or the Presbyterian of Standing Rock?”

A Warrior’s Own Epitaph

By June 1905, Rain-in-the-Face had fallen ill. During the last few months of his life he lay mostly bedridden in his small log cabin, a faithful pet dog keeping him company.

It was during this time that Standing Rock Reservation Christian missionary Mary C. Collins would attempt to procure a confession from him regarding killing George A. Custer. He had long denied knowledge of it, telling her, “My niece, there was so much smoke and dust we do not know, we could not see.” After imploring him to tell her the truth for the sake of history, he apparently rose up on his elbows and said, “Yes I killed him. I was so close to him that the powder from my gun blackened his face” and collapsed back into his pillow.

Historian Charles Eastman also visited the septuagenarian Sioux and recorded the old warrior’s memories of his life, in which he firmly denied killing George A. Custer or having any knowledge of who did. Eastman was a well-educated Santee Sioux whom Rain-in-the-Face liked and trusted. Eastman’s interview with the dying Hunkpapa would be published in his Indian Heroes And Great Chieftains in 1918.

Rain-in-the-Face was never a chieftain. Whether or not he was a hero is open for debate. He lacked the wisdom, temperance and conviction of Sitting Bull. He was without the statesmanship of Red Cloud or the selfless nobility and military genius of Crazy Horse. He was, however, a remarkably complex and controversial figure of his time, and his life was not without courage and achievement.

Rain-in-the-Face had fought bravely for his people in their defiance of white encroachment. He was a fierce warrior, but despite his reputation among the whites as a “fiend incarnate,” as the widow Elizabeth Custer famously proclaimed him, he was no more ferocious a Lakota warrior than most. Through bravery, dedication and force of personality, he had ascended from warrior to war leader and eventually Hunkpapa band leader. He had then been humbled by subjugation, physical ailment and tribal insignificance. With his vanity demanding he remain relevant and capable of gross contradictions, he sometimes gloried in his unfounded notoriety as the slayer of Custer and for an act of cannibalism he did not commit. Still, the old Lakota appears to have held little bitterness during his final days. His words to Charles Eastman two months before his death at Standing Rock Reservation on September 14, 1905, were those of a man finally at peace with himself and his approaching end.

“I fought for my people and my country. Rain-in-the-Face was killed when he put down his weapons before the Great Father. His spirit was gone then; only his poor old body lived on, but now it is almost ready to lie down for the last time. Ho Hechetu! (It is well!)”

– Bob Boze Bell, True West Archives –

James B. Mills resides in Australia and has spent much of his life researching the Plains Indian Wars and the American West. (This article is affectionately dedicated to Leon Claire Metz, under whose tutelage it was partly written.)