![]() Clint Eastwood is a mystery. He’s been a cowboy, a cop, a National Geographic photojournalist, a clown, a honky-tonk singer, a jazz DJ and a moonlighting hit man who doubled as an art professor. But these are roles.

Clint Eastwood is a mystery. He’s been a cowboy, a cop, a National Geographic photojournalist, a clown, a honky-tonk singer, a jazz DJ and a moonlighting hit man who doubled as an art professor. But these are roles.

Who Eastwood truly is is an actor, a director, a jazz player, a family man and, briefly, a mayor. On either side, Eastwood is the King of Cool. Even while Dirty Harry took out his mighty .44 magnum, three-pound hog leg and offered to blow the bad guy’s head clean off, he had time to finish

his hot dog.

Eastwood is something more as well—he’s 81. He’s got energy and ambition—maybe that’s a definition of will—but however you add it up, it adds up to a different definition of cool.

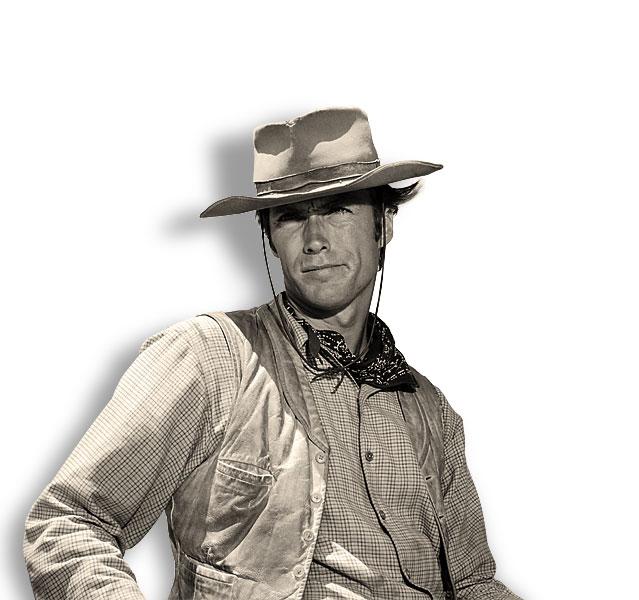

In the late 1950s and early ’60s, when Eastwood started his incredibly slow career ascent in CBS’s Rawhide, no one would have imagined that the improbably named Rowdy would have eventually gone on to become so famous—so distinguished.

Imagine: Eastwood and Sean Connery were born only a few months apart, in 1930, but in 1965, Connery was wrapping the fourth James Bond movie and was the biggest action star in the world, while Eastwood was still, well, Rowdy Yates.

Eastwood seems like the character in the old Mae West song, a guy what takes his time. He was married. He acted in a popular Western series. He was studying other movies and other directors. And he was hanging out in jazz clubs on the West Coast, digging Bud Shank, Art Pepper and future composer Lennie Niehaus, who would eventually score most of Eastwood’s motion pictures.

Around the same time, Eastwood was hired to play an unshaven cowboy in a dirty serape. The movie was made in Spain, the cast and crew spoke next to no English and the possibility that anyone would ever see the picture was pretty dismal. Eastwood figured he’d get a few bucks and a free trip to Europe, and he was close to right. In fact, no one on this side of the Atlantic did see the movie for a couple of years. In the meantime, Rowdy went back to Rawhide. Don’t try to understand ’em, just rope, throw and brand ’em.

But he liked the movie, and he made another with the same director, Sergio Leone, who was doing something remarkable, even if the only American people who enjoyed them were teenage boys. Eastwood asked Leone to trim his dialogue, understanding that the less he spoke, the cooler he seemed. It was incredibly smart of him, but he’d already seen how well that same strategy worked in Rawhide. He was one of the only hip Western characters on TV.

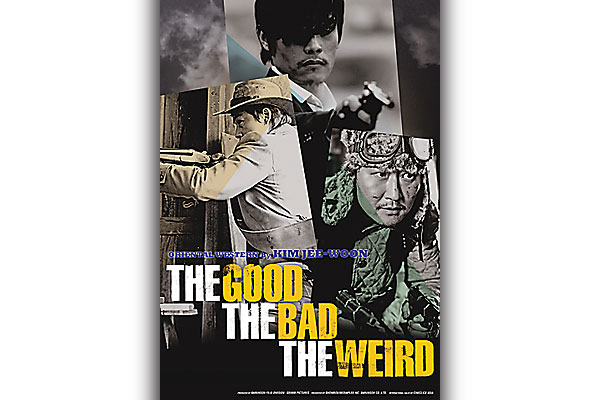

By the time A Fistful of Dollars begat For a Few Dollars More, which begat The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, the series Rawhide was finished and Eastwood was a Western star. More important, he was an underground Western star. By luck or sheer genius, the field had been cleared, meaning that John Wayne was finished.

Eastwood turned his back from the fourth Leone movie, Once Upon a Time in the West, and began making a domestic Western, Hang ’em High. But his next real break came when he forged a bond with American director Don Siegel. Between them they made the coolest urban Western movie in history, Coogan’s Bluff.

While he and Siegel added projects, Eastwood took his first steps to becoming a director. By 1971, Eastwood had directed his first movie, Play Misty for Me, and Dirty Harry had become a brand name.

But the story, or rather the mystery, of Clint Eastwood is bigger and more interesting. You can say that he made a great many stinkers. You can say Eastwood rarely took grand chances as a director (and if J. Edgar is any evidence, he’s not likely to start now). But we’ve seen that Eastwood does really solid work when he’s working with strong actors and outstanding writers. How do you encapsulate a career that long and lumpy?

Here’s a clue: Eastwood’s cool is all about structure and pace. Here’s another clue: the best performance we’ve seen in an Eastwood role came from John Malkovich, in a movie he didn’t direct, 1993’s In the Line of Fire. It came when Eastwood was free of control. The third clue is Eastwood’s best directorial performance comes when he’s over the top, as he was in 2008’s Gran Torino. It’s not a great film, but it had a lot of heart, and that’s worth something—it proves that Eastwood can have fun chewing scenery, when he isn’t taking himself so seriously.

Our beloved film genre is nearly a dirty word; Eastwood seems to want to avoid making a Western. But Eastwood needs a strong Western, and we need to see one, very possibly one he won’t, or shouldn’t, direct. Our Executive Editor Bob Boze Bell likes to think about the idea of filming the actor in a late Earp story. Personally, I’d like to have Eastwood channel Harry Carey, who John Wayne called the “greatest Western actor of all time,” making something with wit and a bit of boyish charm.

It’s time for the Rebirth of Cool.

Henry Cabot Beck is the film editor for True West, writes about pop culture in general for other publications and is a member of the Phoenix Film Critics Society.

Photo Gallery

Clint Eastwood is a mystery. He is the King of Cool.

Illustration by Bob Boze Bell

–Clint Eastwood in Rawhide, courtesy CBS –