All Sam Gwynne wanted to do was write a book about the American West, specifically about Quanah Parker and the Comanches. “I would have been happy if it had sold 2,000 copies just because I wanted to do it and I loved the subject,” Gwynne says from his home in Austin, Texas.

All Sam Gwynne wanted to do was write a book about the American West, specifically about Quanah Parker and the Comanches. “I would have been happy if it had sold 2,000 copies just because I wanted to do it and I loved the subject,” Gwynne says from his home in Austin, Texas.

His publisher might have expected a few more sales than that, but even Scribner certainly wasn’t thinking bestseller. “The first printing I seem to remember was less than 10,000,” Gwynne says. “That’s where my publisher thought it would be.”

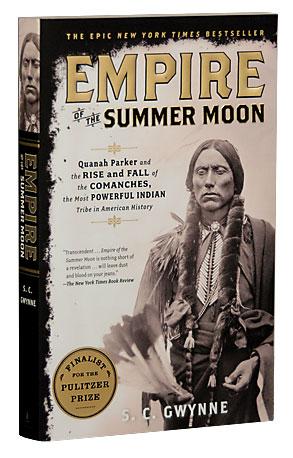

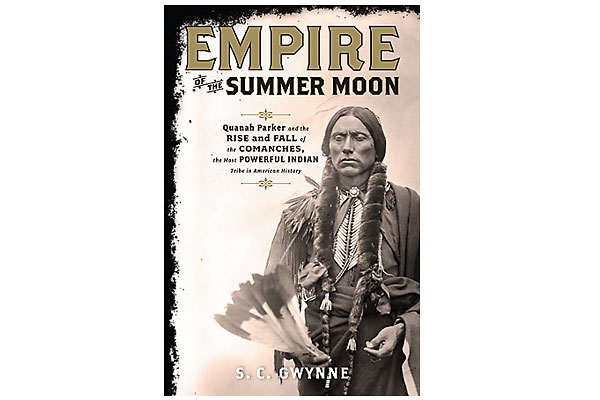

Gwynne’s book, Empire of the Summer Moon: Quanah Parker and the Rise and Fall of the Comanches, the Most Powerful Indian Tribe in American History, however, took American readers by storm. Since its debut in 2010 and paperback release in 2011, sales have approached 500,000.

Warner Bros. has paid Gwynne for an 18-month option, with Academy Award-winning screenwriters Larry McMurtry (anyone remember the novel Lonesome Dove?) and Diana Ossana, director Scott Cooper (who helmed Jeff Bridges’s Oscar-winning turn in Crazy Heart) and producer Michael Costigan (head of Ridley Scott’s production company, whose films include The Taking of Pelham 1 2 3 and Robin Hood) attached to the project. PBS is planning an episode of American Experience based on the bestseller, and screenwriter Dan Gordon has talked about developing an HBO-type series.

“I just wanted to do a good book and be able to stand with the Fehrenbach book,” Gwynne insists.

Well, T.R. Fehrenbach’s 1974 book, Comanches: The Destruction of a People, has plenty of admirers. While it’s likely the definitive history of the Comanches, it certainly didn’t capture the imagination the way Gwynne’s book has succeeded in doing nationwide. Reviewers praised it, drawing favorable comparisons to Dee Brown’s Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee and Hampton Sides’s Blood and Thunder.

Yet before we continue with this meeting of the Empire of the Summer Moon fan club, let’s point out that not everyone likes Gwynne’s history.

The biggest critic might be Nocona Burgess, a renown artist who is not only Comanche, but happens to be one of Quanah Parker’s great-great-grandsons.

“Even on cultural things, some things he writes are silly,” Burgess says. “He made the Texas Rangers sound like a bunch of rowdy whiskey-drinking guys, but he didn’t write about the atrocities that they did to us. He made us sound like these marauding rapists. Culturally, that was really frowned upon. It wasn’t really practiced. Sure, some guys did it to exact revenge. I’m not saying that we were saints, and I’m not saying it didn’t happen, but it wasn’t a practice.”

Mainly, Burgess argues that Gwynne should have talked to Comanches to get the culture straight, and to present another side of the story. Then there’s the matter of Quanah Parker’s father. Peta Nocona was killed, Gwynne writes, when the Texas Rangers raided the Comanches’ camp in 1860 and recaptured Quanah’s mother, Cynthia Ann Parker, who had been abducted during an 1836 raid at Parker’s Fort, Texas. The Comanches have always denied this.

“He didn’t have a Facebook page to tell everyone, ‘Hey, I’m still alive,’” Burgess says. “And the reason they moved Cynthia Ann around so much across Texas is because Peta was looking for her.”

Gwynne stands his ground. He didn’t want to be considered “in their camp” by talking to Comanches, and he thinks Peta Nocona died on the Pease River in North Texas in 1860.

“I disagree with their version of the death of Nocona,” he says. “They are never going to agree with me on that. Ever. And I just think that a historian’s approach would be not to interview someone in 2008. I like Nocona and respect him, and think he’s a good guy. We’re friends on Facebook, and I respect his position fully. I just don’t think that they can add to something that happened 200 years ago.”

Some academic historians have challenged some facts in Gwynne’s book and questioned some of his sources.

“My bet is that professional (academic) historians will not adopt the Gwynne book for classroom use in the same way they have adopted Pekka Hamalainen’s Comanche Empire,” says Paul H. Carlson, a history professor at Texas Tech University who teamed with Tom Crum to write Myth, Memory and Massacre: The Pease River Capture of Cynthia Ann Parker.

Still, Carlson isn’t surprised by the reaction to Gwynne’s book. “It got such publicity, and he writes so darn well,” Carlson says. “It’s a great story.”

Even Burgess sees some positives from the Empire buzz.

“Sure. People are interested in the Comanches, because it is a great history. We were conquerors, we were warriors and what we did with the horse kind of propelled the entire Plains tribes. I think our history is fascinating.”

On the other hand, one might reason that Gwynne’s book would have prompted criticism from the Lakota for that subtitle: Most Powerful Indian Tribe in American History. What about Fort Phil Kearny, Little Big Horn, Crazy Horse, Sitting Bull and Red Cloud’s war?

“These Lakota were incredible warriors and incredible horsemen,” Gwynne says with a laugh, “but what I mean by that was the ability to transform and change history, and sitting up there in the Northern Plains, they just didn’t. Period. Their conflicts were primarily military, and way after the Comanches, and did not affect the settlement of the West much. Power is the ability to change, and the Comanches did that.”

Adds Burgess: “I told a guy in Texas that if it weren’t for smallpox and other diseases, you guys would be speaking Comanche now.”

Back to the movies. Quanah Parker certainly has Hollywood written all over.

His mother was a white woman, Cynthia Ann Parker, kidnapped when she was around nine years old during a Comanche raid. Peta Nocona later took her for his wife, and she bore him two sons and a daughter. In 1860, Texas Rangers raided a Comanche camp on the Pease River and recaptured Cynthia Ann. Her young daughter died a few years later, and Cynthia Ann died—of a broken heart, romantics say—in 1870.

Meanwhile, Quanah became leader of the Kwahadi (sometimes spelled Quahadi) band of Comanches. He embarrassed Ranald Mackenzie and his Army soldiers at Blanco Canyon in 1871, showed his bravery during the attack on the buffalo hunters’ stronghold at Adobe Walls in 1874 and reluctantly led the last band of Comanches to surrender in 1875. Appointed chief of the Comanche nation on the reservation, he adopted his mother’s last name and guided the Comanches in peace, befriending powerful white men in Texas (ranchers) and Washington (politicians). He became so popular in Texas, a town was named after him. It was Quanah who persuaded President Theodore Roosevelt to establish Oklahoma’s Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge in 1901. Late in 1910, a few months before his own death on February 23, 1911, Quanah had the remains of his mother and sister re-interred at a cemetery near his home in Cache, Oklahoma. He sure loved his mother. Today, Quanah is buried alongside his mother and sister at the post cemetery at Fort Sill in Lawton, Oklahoma.

What writer wouldn’t be drawn to that story? And there have been plenty, from Zoe A. Tilghman (widow of lawman Bill Tilghman), who wrote 1938’s Quanah: The Eagle of the Comanches, to biographers William T. Hagan (1993’s Quanah Parker, Comanche Chief) and Bill Neeley (1995’s The Last Comanche Chief: The Life and Times of Quanah Parker). The renown Dorothy M. Johnson’s Spur Award-winning short story from 1957, “Lost Sister,” is a re-imagining of the Cynthia Ann Parker story. In 1982, novelist Lucia St. Clair Robson triumphantly tackled the story of Cynthia Ann in her best-selling, Spur Award-winning debut Ride the Wind, which is still in print. Charles Brashear put his own spin on the legend in his 1999 novel Killing Cynthia Ann. Acclaimed writer Douglas C. Jones fictionalized a Quanah-inspired hero and the Comanches in the novels Season of Yellow Leaf (1983) and Gone the Dreams and Dancing (1984). George W. Proctor told Quanah’s story in his 1996 novel Blood of My Blood.

“It’s a story that is told over and over again,” says Glenn Frankel, a Pulitzer Prize-winning newspaper reporter now teaching at the University of Texas in Austin, “and each telling fits its generation.”

Frankel plans to add to the tome of literature on Quanah, Cynthia Ann and the Parkers with a book on the many versions of the Parker story.

So why hasn’t Hollywood noticed Quanah, Cynthia Ann and the Comanches before?

“Actually,” Frankel says, “Hollywood has.”

He points to the 1956 classic Western The Searchers, directed by John Ford and starring John Wayne and Natalie Wood, as a retelling of the Cynthia Ann Parker abduction.

Quanah also wound up in other movies. He was played as a peace-seeking chief by New York City-born Kent Smith in 1956’s Comanche, which was advertised as “The Saga of the One Indian Nation That Killed More White Men Than Any Other Tribe in History.”

Bloodthirsty advertising aside, Comanche, like a handful of movies made in the 1950s (Broken Arrow, Devil’s Doorway, Tomahawk), was slightly sympathetic to the Indians. It just wasn’t very good.

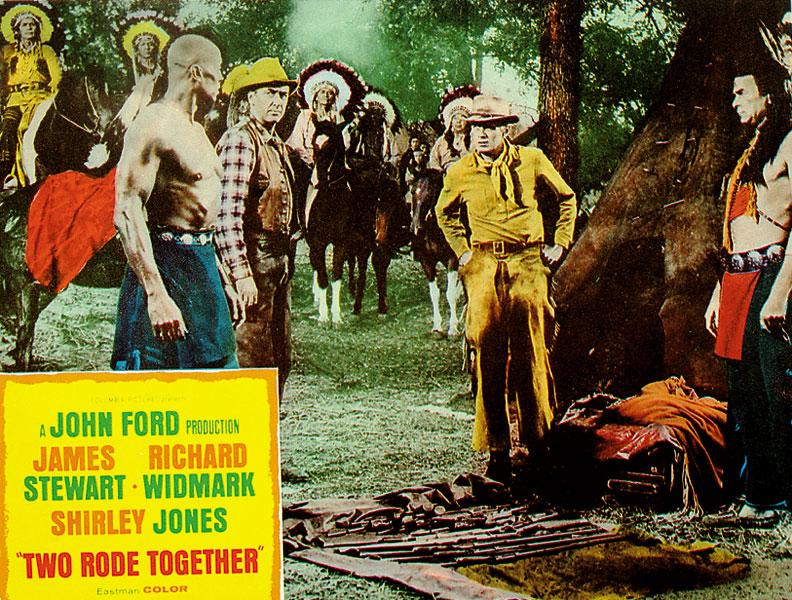

“John Ford also commissioned a screenplay on Quanah Parker, so he knew about Quanah,” Frankel says. “But then WW II came along, and the movie never got made. Although he did make Two Rode Together [in 1961], which he didn’t like and isn’t very good, and Ford said he did it for the money.”

That one cast German-born Henry Brandon—who played the bad Comanche in Comanche—as Quanah and black actor Woody Strode as another Indian. Despite starring James Stewart, Richard Widmark and Shirley Jones, it fared poorly at the box office.

The best Quanah had to be Quanah himself. That’s right. In 1908, Quanah appeared in The Bank Robbery, a two-reeler filmed in Cache by the Oklahoma Natural Mutoscene Company. Its all-star (for Western history buffs, that is) cast included bank robber Al Jennings and lawmen Heck Thomas and Bill Tilghman.

“It is really weird to see,” Gwynne says. A print is at the Library of Congress, and the movie showed up on the now-out-of-print 1980 video Film Classics: The Origins of Cinema, Volume VI from Kartes Video Communications.

So who should be cast in a film version of Empire of the Summer Moon?

“I honestly don’t know Hollywood,” Gwynne says. “I think it should be either a Native American actor of mixed blood, like Quanah, or a Mexican actor whose blood would be to some similar extent to Quanah’s. I think [Spanish] Javier Bardem is a great actor and he could play the old Quanah.”

And Cynthia Ann?

“In early 1982, months before [Ride the Wind] came out, Ballantine president Marc Jaffe took my editor and me to lunch,” Robson recalls. “He opened with, ‘So, who do you think should play Cynthia Ann?’ We agreed that the blonde Texan star Sissy Spacek would be a good choice. As years went by, Melanie Griffith’s name was mentioned, and I sent a copy of the book to Daryl Hannah. Blonde actresses in their 20s have started looking alike to me. Line them up, and I probably couldn’t name them. One more reason why my pick for Cynthia Ann is what it’s always been: either a relatively or a completely unknown actress. Same for the young and adult Quanah.”

Carlson thinks Empire of the Summer Moon could be turned into a good movie.

“It would be fiction, of course,” he says, “but that’s what they do with the books about Cynthia Ann Parker. They don’t know what happened. They can only speculate on what they think happened. It would be the same with Quanah Parker.”

Before we start casting Empire of the Summer Moon, there’s another major concern. Gwynne’s book is so often graphically violent, it begs to ask: Can you make a movie like that given Hollywood’s politically-correct mentality today?

“That’s something that will have to be addressed,” Frankel says. “That period was violent, but what the Comanches were doing, what other tribes were doing, and what the whites were doing to them is no different than what’s happening in Afghanistan, Bosnia and all over the world.”

Gwynne agrees. “I think that’s one of the biggest challenges to a director: to figure out how to do it without driving everybody out of the theater,” he says. “Somehow, you’ve got to suggest it. But if you have the right director, I think you can do it.”

Meanwhile, Empire of the Summer Moon is a hot topic in Hollywood, across the country, even in Lawton, Oklahoma, headquarters of the Comanche Nation.

“Most optioned books never get made into movies,” Gwynne says. “It’s a very long shot. Needless to say, I would be thrilled if they actually did make a movie out of it.”

Even Nocona Burgess has hopes for a theatrical version of Empire of the Summer Moon.

“If they do it right,” he says. “I just hope it’s not that same old murdering, raiding, raping story they’ve done for ages. McMurtry’s doing the script, so hopefully he’ll at least tell the Comanche side of the story. But, then again, he also did [the novel and 2008 miniseries] Comanche Moon, and that was terrible.”

In Johnny D. Boggs’s next novel, Quanah Parker’s 1885 near-death experience in Fort Worth becomes a nefarious murder plot. Kill the Indian, a Daniel Killstraight mystery, is due out in June from Five Star.

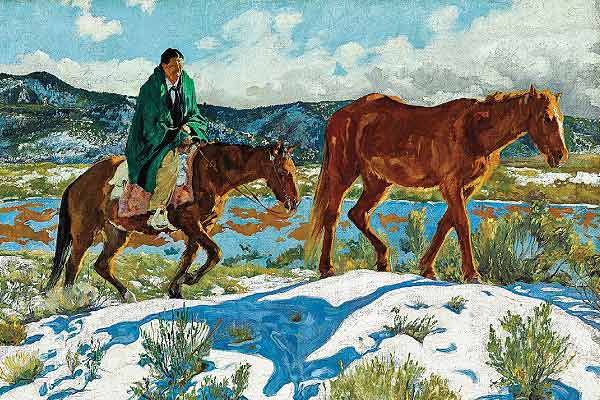

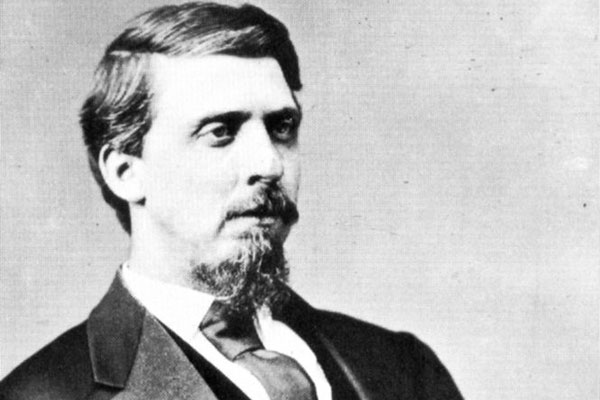

Photo Gallery

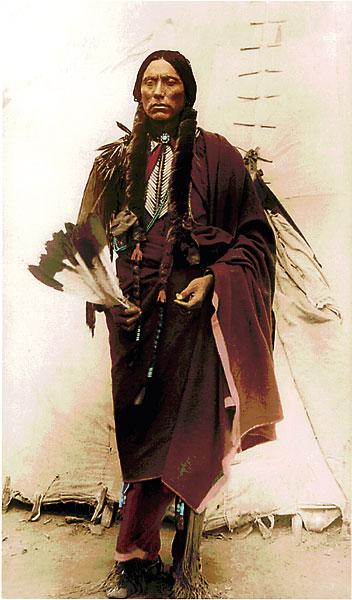

—Nocona Burgess, Quanah Parker’s great-great grandson (above)

–Photo courtesy Michael Gunby–

– All images courtesy Johnny D. Boggs unless otherwise noted –