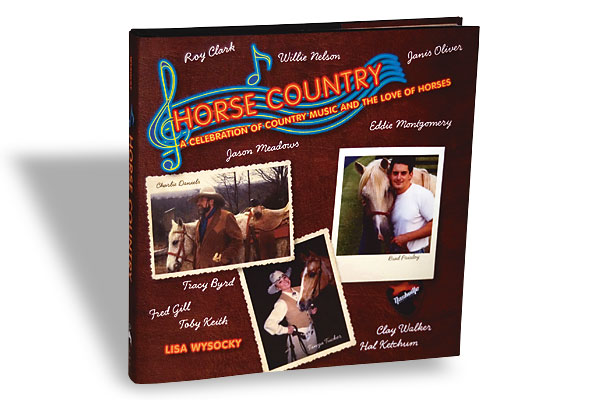

presents a view of the luxury dining some frontier railroad passengers enjoyed.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

Hopeful pioneers boarded trains bound for the frontier, but found little pleasure other than a basic seat. If a passenger lowered a window for some fresh air, embers and soot from the engine drifted in. Neither air conditioning nor heat was available.

Without even these leanest of luxuries, most passengers also did not dine on the train, despite the fact that George Pullman had invented dining cars in the late 1860s. Expensive to build, they were not installed on all routes. Passengers usually had to get off the train and eat at dining stations that offered less-than-palatable fare. If a train did offer a dining car, passengers found an eight-to-10-person crew of cooks, wait staff and a steward at their service.

One railroad—the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy—advertised itself as the guide to the gold fields of Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Arizona. The railroad offered 75-cent meals in elegant dining cars.

The journey onboard these trains heading west was indeed an event. Charles Nordhoff, a Prussian immigrant, described his luxury rail travel in the 1870s: “…your dinner is sure to be abundant, very tolerably cooked, and not hurried; as you are pretty certain to make acquaintances on the car; and as the country through which you pass is strange, and abounds in curious and interesting sights, and the air is fresh and exhilarating—you soon fall into the ways of the voyage, and if you are a tired businessman, or a wearied housekeeper, your careless ease will be such a rest as certainly most busy and overworked Americans know how to enjoy.”

He also described the dining car of his train “…as neat, as nicely fitted, as trim and cleanly, as though Delmonico [American restaurateur Lorenzo Delmonico] had furnished it; and though the kitchen may be in the forward end of the car, so perfect is the ventilation that there is not even the faintest odor of cooking.

“You sit at little tables which comfortably accommodate four persons; you order your breakfast, dinner, or supper from a bill of fare which…contains a quite surprising number of dishes, and you eat, from snowwhite linen and neat dishes admirably cooked food, and pay a moderate price. It is now the custom to charge a dollar per meal on these cars; and as the cooking is admirable, the service excellent, and the food various and abundant, this is not too much. You may have your choice in the wilderness, eating at the rate of twenty-two miles per hour—of buffalo, elk, antelope, beefsteak, mutton-chops, grouse….”

In 1892, savvy businessman Fred Harvey expanded a partnership with the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway to include dining cars. “Meals by Fred Harvey” became a slogan that helped build the Santa Fe’s reputation as one of America’s great railroads. The luxury menu items included oysters, stuffed turkey, beef au jus, salmi of duck, sweet potatoes, baked veal pie, lobster salad, French slaw, mince pies, ice cream, French coffee and a variety of cheeses—all for about $1 each. Dining evolved as much as the Western landscape itself did.

Imagine dining on a rail car headed for the frontier when you make the 1883 recipe for lobster salad, a tasty, 19th-century dish.

*** R E C I P E ***

~ Lobster Salad ~

2 cups lobster, cooked and chopped fine

¼ tsp. freshly ground pepper

½ tsp. mustard

½ tsp. salt

½ cup mayonnaise

¼ cup lettuce, shredded

Lettuce leaves for plating

Bread slices

Place all the ingredients in a bowl and combine well. Serve on a bed of lettuce with toast points. To make toast points, toast slices of bread and cut into triangles.

Recipe adapted from 1883’s Colorado Cook Book

Sherry Monahan has penned The Cowboy’s Cookbook, Mrs. Earp: Wives & Lovers of the Earp Brothers; California Vines, Wines & Pioneers; Taste of Tombstone and The Wicked West. She has appeared on Fox News, History Channel and AHC.