— All images True West archives —

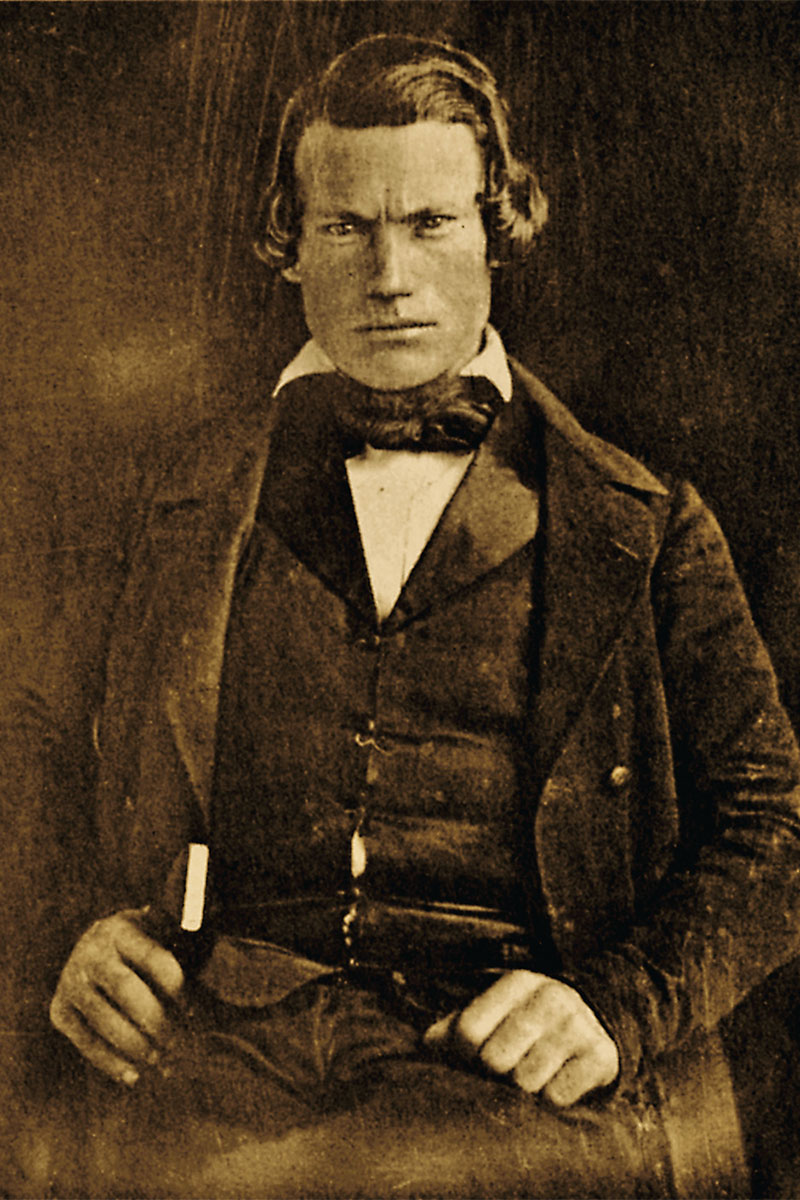

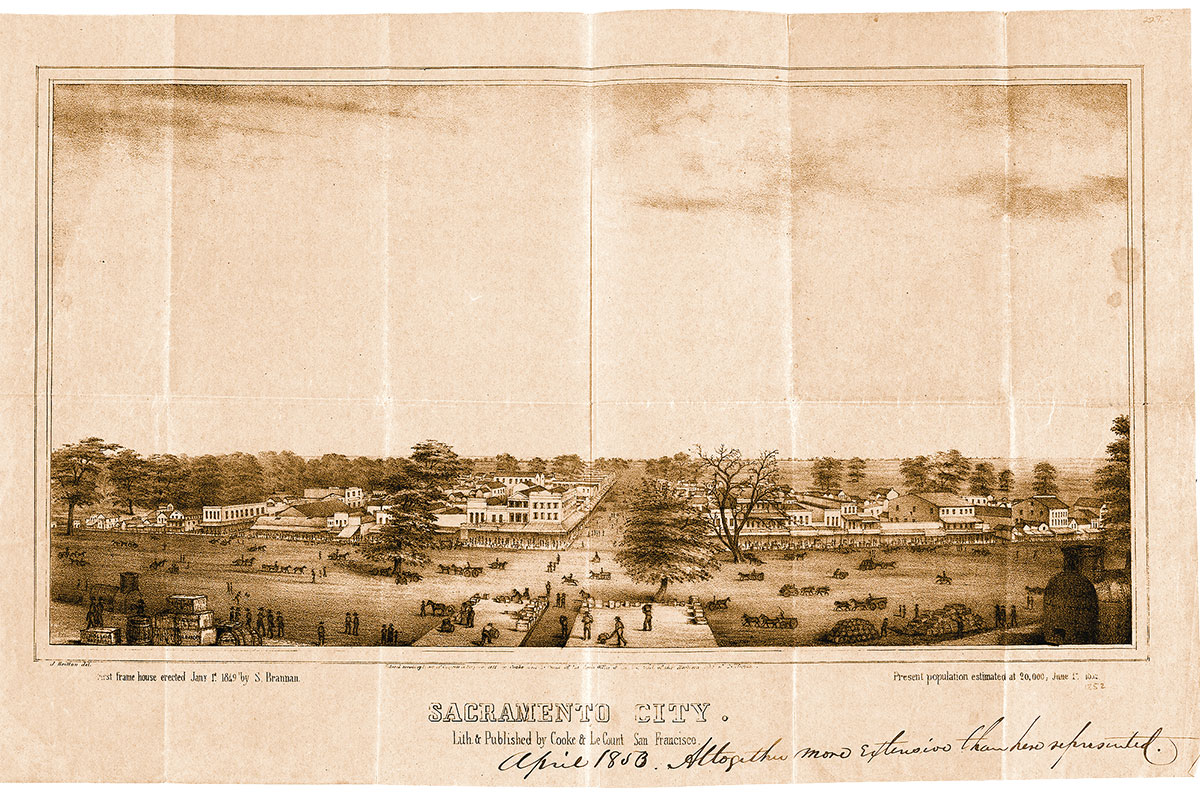

On May 17, 1853, the legislature passed an act creating the California Rangers, with Harry Love as their captain, and Governor John Bigler signed it into law. It authorized the formation of a company, not to exceed twenty men, for service of three months, unless earlier disbanded. Each enlistee was to be paid $150 a month, but was required to furnish his own horse, weapons, equipment, and provisions.…[I]t was clear from the outset that this ranger force was established for the sole purpose of eliminating the Joaquin Gang of outlaws….

— Illustration by Bob Boze Bell —

…Once his rangers were assembled in late May, Captain Love led the company out in his historic manhunt. For more than a month he and his men explored the San Joaquin Valley and Sierra foothills, searching for leads to the gang’s current location.

Information derived from interrogation led them on across the Coast Ranges to Mission San Jose, where Murrieta was said to visit occasionally. There Love made his first notable arrest on July 10, when his rangers collared Jesus Feliz, a known confederate and relative by marriage of the gang leader. After an intensive interrogation of Feliz, Love took his prisoner and company fifty miles south to San Juan Bautista….

Why Feliz, a hardened criminal, assisted his captors in their quest for his former partners in crime can only be surmised.…He may have tired of the frenetic outlaw life, especially after seeing two of his brothers die violently, or he may have simply opted for gut spilling in return for leniency in coming court action. In any event, Love took him along on the hunt, and the information he provided proved essential to the California Rangers’ ultimate success.

With provisions for an eighteen-day foray, Love’s men spread the word at San Juan Bautista that they were heading off on a scout down the coast. This was deliberate subterfuge intended to foil the passing of their actual plans to Joaquin by any pueblo residents in league with the bandits. Love led his rangers into the Salinas Valley and stopped in the afternoon, evidently to spend the night. But when darkness fell, he had them break camp, mount up, and make a forced march along the San Benito River to Panoche Pass in a remote section of the Coast Ranges. He set up camp there and sent out scouting patrols looking for signs of the Murrieta band.

— Courtesy Wells Fargo Bank —

Not one to sit in camp and wait for his men to report, Love, with Feliz in tow, took charge of a scouting party himself. Following his nose, his trailing instincts, and perhaps suggestions from Feliz, he led the patrol southward for some twenty miles. On July 20, he came on a deep canyon where Mexican mustang hunters were encamped with a herd of several hundred horses. Brands on some of the animals made it clear that not all were wild mustangs, and Love suspected the herd included horses stolen from ranches on the coast. Without alerting the Mexicans to his presence, he headed back to his own encampment for reinforcements.

— Courtesy True West Archives —

The next day he returned with his entire ranger company and rode directly into the camp. While the Mexicans, some of whom were probably Murrieta gang members, silently glowered, he and his men examined the suspect horses and confiscated eight that they believed had been stolen. After telling the mustangers he was taking the horses to San Juan Bautista for positive identification, Love departed with his rangers. Believing this incursion would send the mustang hunters straight to Murrieta to warn him that lawmen were hot on his trail, Love made camp about ten miles away from the canyon and waited three days, allowing the mustangers ample time to round up their horses and move out. On July 24 he and his rangers returned to an empty canyon. Tracks revealed that the mustangers had moved their herd westward, down the canyon. Convinced that his ploy had worked and the mustang hunters would lead him straight to Murrieta, Love rested his men the remainder of that day and evening in preparation for what was likely to be an exciting day on the morrow.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

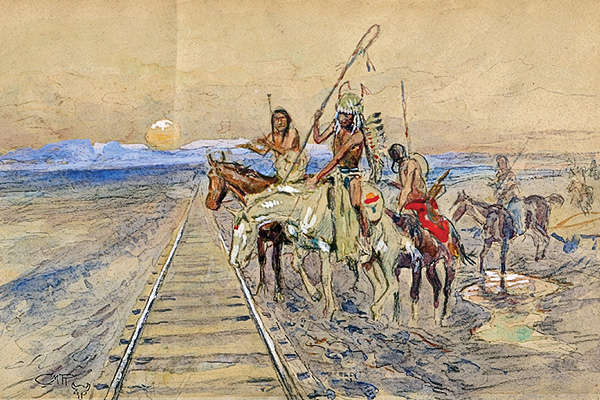

At two o’clock in the morning on July 25 the rangers moved down the canyon to the valley below. Dawn was breaking when they spotted smoke from a campfire some three miles ahead. Love and his men rode hard toward this site and got within four hundred yards before they were discovered. Startled cries rudely awakened the Mexicans—a mixture of mustangers and Murrieta gang members—as the rangers thundered into the camp. Pandemonium reigned. Most of the mustang hunters ran for their horses, while the bandidos went for their guns. The mounted rangers herded those fleeing back into the camp at gunpoint.…

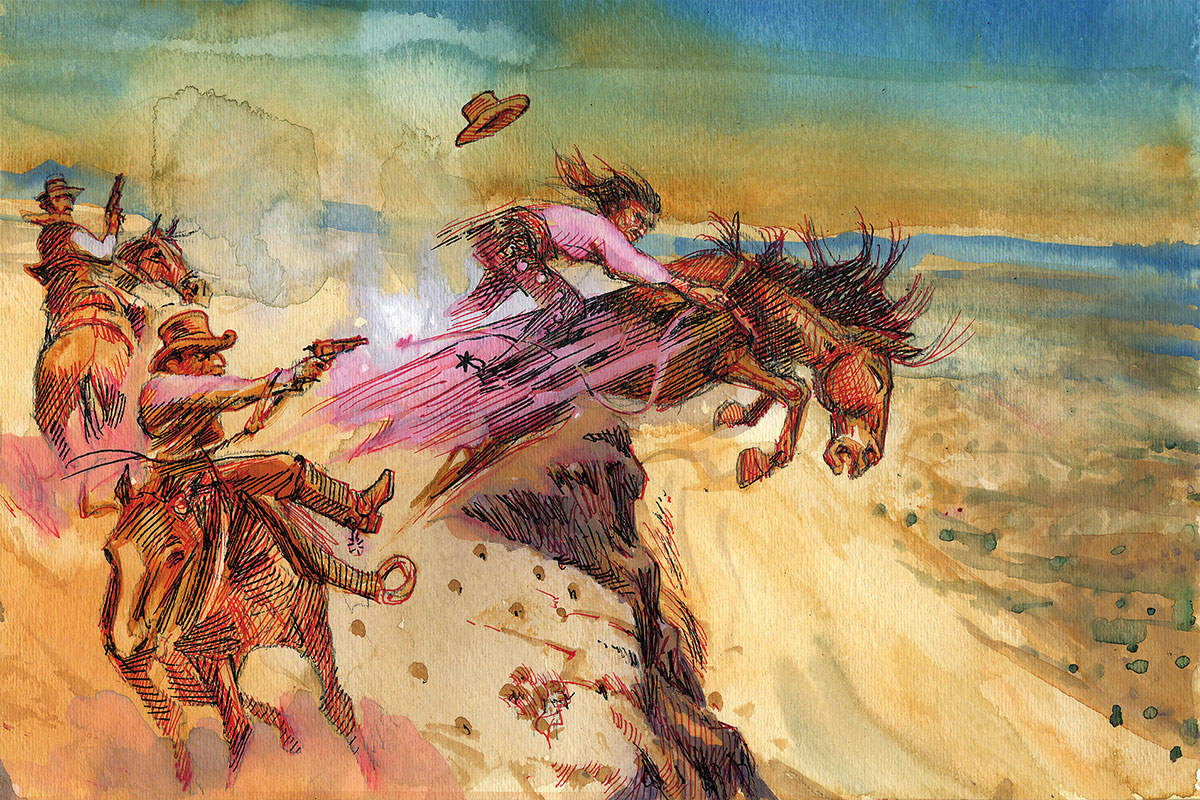

—Illustration by Bob Boze Bell —

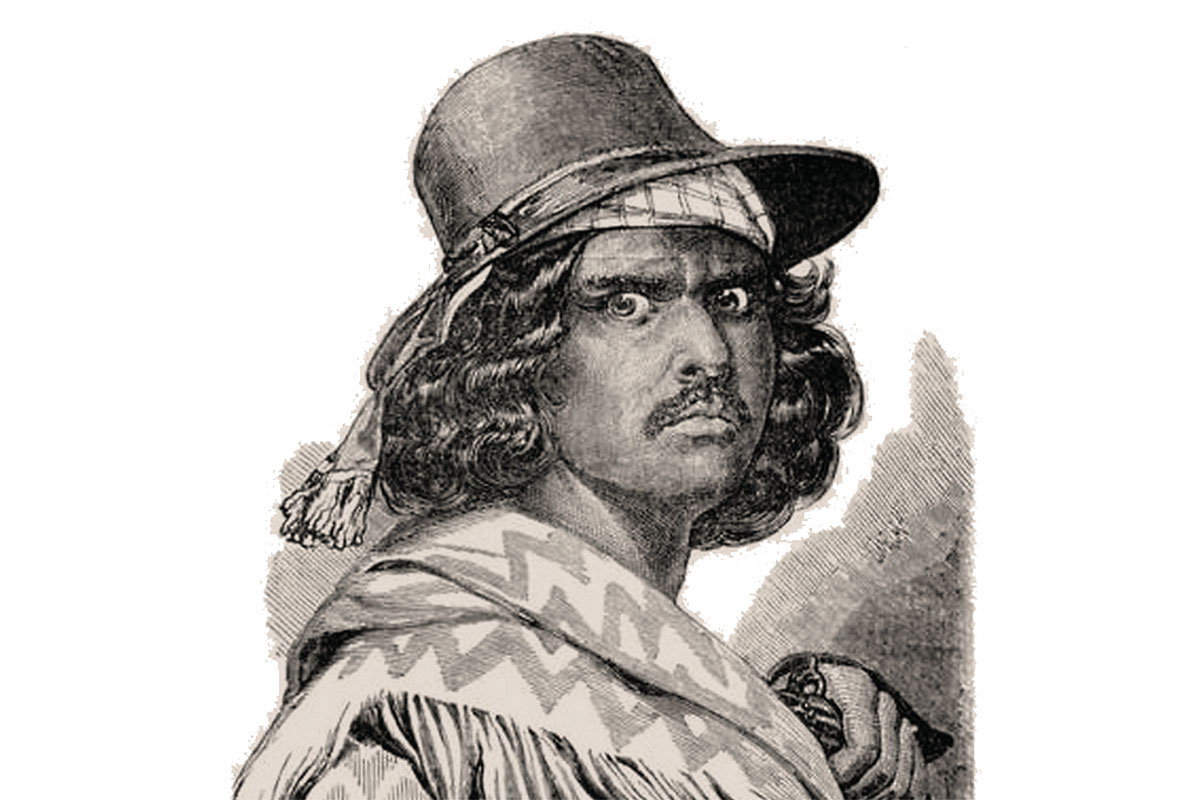

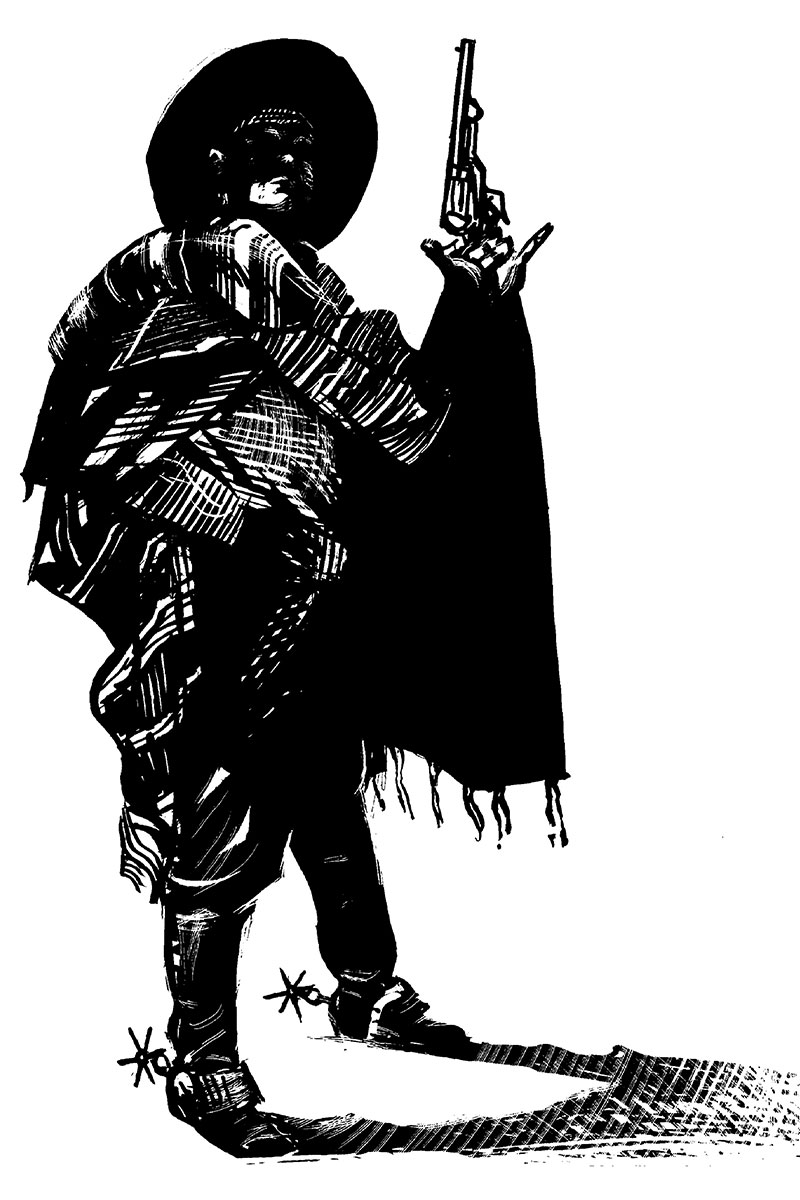

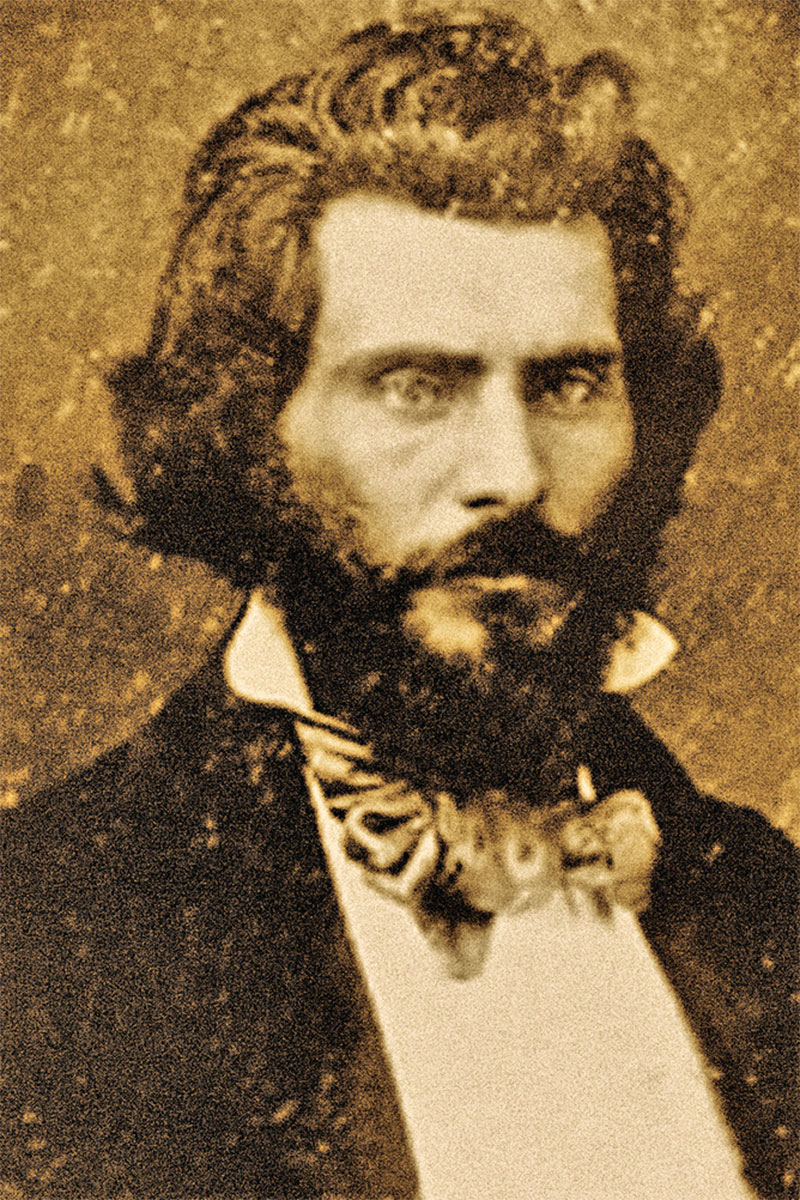

One man, “a handsome, long-haired, fair-complected young Mexican of about twenty-three,” standing beside his horse at the edge of a deep arroyo, stepped forward and said, “Talk to me. I am the leader of this band.” Ranger Bill Byrnes reined up at this point, took one look at the man, and recognized him as the one they sought. “This is Joaquin, boys!” he shouted. “We have got him at last!” Hearing this, one of the bandit chieftain’s followers, later identified as Bernardino “Three-Fingered Jack” Garcia, pulled out a pistol and triggered off two rounds, directing his fire at the ranger captain. One bullet grazed Love’s head and made a new part in his hair while the other missed entirely. An immediate answering salvo of nine shots fired by Charlie Bludworth, Bill Henderson, and two other rangers riddled the body of Three-Fingered Jack. To make sure he was dead, Bill Byrnes and Love each pumped a round into his head. Garcia had lived only seconds after shooting at Love, but if his intention was to divert the rangers’ attention from his leader and give Murrieta a chance to escape, he was successful, at least for a few moments.

Before the rangers could grab him, Murrieta vaulted onto his horse and, riding bareback, dropped down the embankment to the creek below and raced off along the arroyo floor. Henderson, the closest ranger to the fleeing bandido, emptied the other barrel of his shotgun at him, but his horse shied, causing him to miss. Dropping the scattergun, Henderson spurred his horse in pursuit. At full gallop, he fired his six-shooter, hitting Joaquin’s mount in the leg, but the animal continued on. A second pistol shot dropped the animal, but Murrieta sprang to his feet and ran off down the canyon. Ranger John White rode along the rim of the arroyo, firing his rifle at the wanted gang leader as Henderson continued his six-shooter fusillade. The long-sought bandit chieftain finally pitched forward into the creek with three bullets in his back. When the rangers reached Murrieta, he muttered his last words: “No tira mas. Yo soy muerte.” (“Don’t shoot anymore. I am dead.”)

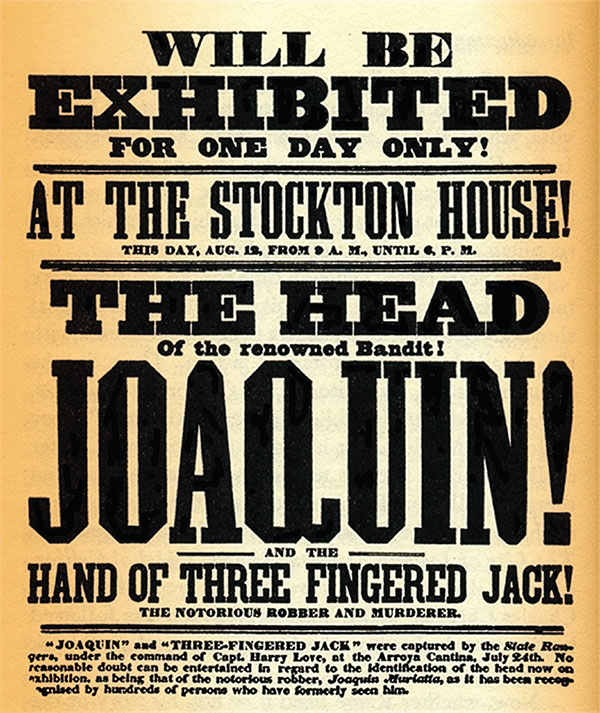

…Captain Love…did what he had to do, an act which was commonly performed in the early West to prove the death of a wanted fugitive: he had his men cut off the head of the bandit Joaquin. In addition, he had them sever the head and deformed hand of Three-Fingered Jack to prove that Joaquin’s lieutenant had also been dispatched. Aware that in the midsummer heat these grisly artifacts would deteriorate quickly, he handed them over to Bill Byrnes and a new recruit named John Sylvester with instructions to hurry to Fort Miller, about a hundred miles distant, and preserve the trophies in alcohol.…

With the grizzly trophies wrapped in a gunnysack and firmly secured behind Byrnes’s saddle…the two rangers crossed the San Joaquin on a ferry operated by Samuel A. Bishop, to whom they explained their mission and displayed the gruesome trophies that were already starting to putrefy. It so happened that Bishop was well supplied with spirits, and he offered help. He produced an empty liquor keg into which the heads and hand were placed and covered with red-eye whiskey from a forty-gallon barrel. The keg was then secured to the back of a hired mule provided by the ferryman, and Byrnes and Sylvester continued on to Fort Miller. There, it was found that the head of Three-Fingered Jack was so badly deformed by the bullets that had killed him and by decomposition that it was useless for identification purposes, and so it was buried. The head of Joaquin and the hand of Garcia were retained in glass jars of alcohol so they could be viewed.

The first public notice of Love’s achievement appeared in the form of a letter to the San Joaquin Republican, with an appended note regarding the weather, explaining Love’s concern about the preservation of his severed heads:

“I hasten to inform you of the death of Joaquin, the robber, who has been such a curse in the country for some time. Captain Byrnes, one of the Rangers, and Mr. Sylvester arrived here yesterday evening with the heads of Joaquin and one of his band, whom they captured at a place called Singing River, about 140 miles from here. The remainder of the party are expected here this evening with two prisoners….The weather is very warm—thermometer 115 degrees in the shade.”

Henry “Harry” Love’s famous manhunt of Joaquin Miller is excerpted from

Chapter 1 of award-winning Western historian Robert K. DeArment’s

Man-Hunters of the Old West, Volume 2, University of Oklahoma Press, 2018.