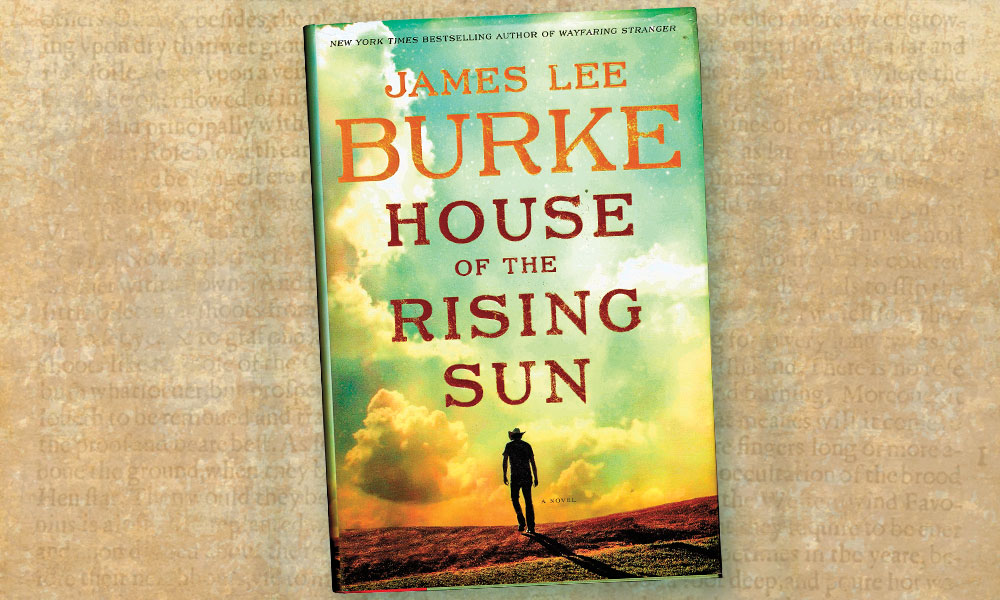

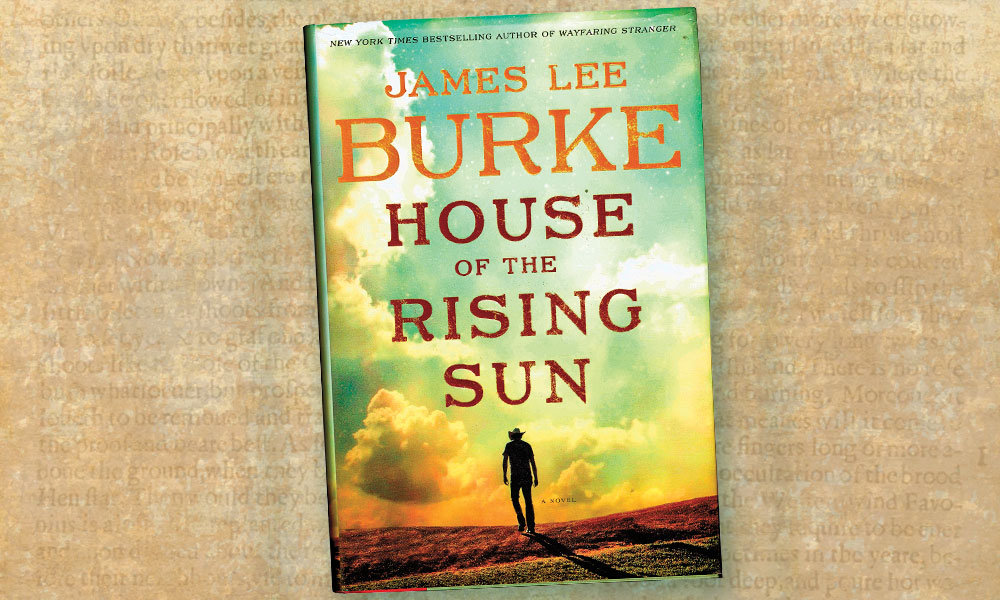

Grand Master mystery novelist James Lee Burke is known best for his popular Dave Robicheaux series (20, to date), but the Houston, Texas, native also has written seven standalone novels, two short-story collections, and three “Holland Family” series books, tracing the lives and generations of Texas Ranger Hackberry Holland, the elder; and grandson Hackberry Holland; grandson Weldon Holland; and nephew Billy Bob Holland. Burke’s fifth entry in the Hackberry Holland series is House of the Rising Sun (Simon and Schuster $27.99), a multi-generational Western that could be considered a standalone novel, comparable to Philipp Meyer’s The Son, Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian and Max Evans’ Bluefeather Fellini.

Burke, who has spent the majority of his life living and writing about the Texas-Louisiana Gulf Coast region, has created a Western novel that echoes the violent and jarring themes of the West’s transformation from the 19th century to the 20th century. Readers will recognize the hero’s struggles to live, adapt and survive in the new modern West—similar to the characters’ struggles in Larry McMurtry’s and Loren Estleman’s recent books, The Last Kind Words Saloon and The Long High Noon, respectively. And, similar to McMurty and Estleman’s latest Westerns, House of the Rising Sun is a vehicle for the author to expound on the questions of life, mortality, sin and family legacy through the voice of his philosophical hero, former Texas Ranger Hackberry Holland. “A great weariness seemed to seep through his body, not unlike a pernicious opiate that told him it was time to rest and not quarrel with his fate. But death was not supposed to come like this, he told himself again.”

As a literary novel, comparable to Philipp Meyer’s The Son, Burke’s House of the Rising Sun is poetic in its prose, with the Texas-Mexico borderlands and Hill Country key characters of the novel. Like Meyer’s use of the Comanche language in his Texas epic, Burke’s use of untranslated Spanish and Texas/Southern dialect brings voice to the bilingual multi-culturalism of the Lone Star State. The violence that pervades the actions of the novel’s hero, Hackberry, and the lives of his family members with his antagonists’ sadism are reminiscent of the cast of characters in Cormac McCarthy’s bloody, violent Texas borderland novels. Hackberry, introduced previously in a Burke short story title “Hack,” is also reminiscent of Elmore Leonard’s novel and short story character Raylan Givens. Hack is a conflicted man of honor and violence, who lives his life on the razor-thin strand of barbwire between the law and criminal behavior. If mercurial film director Sam Peckinpah were alive today, he would clearly identify with Hackberry Holland’s conflicted morals and place in the West’s transition to modernity in the earliest decades of the 20th century. Readers of Max Evans’ Bluefeather Fellini, Craig Johnston’s “Longmire” series and literary classics such as Homer’s Odyssey and Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur will also recognize and appreciate Burke’s allusions to mysticism and faith (especially the influence of Roman Catholicism on everyday life in the Borderlands) in the midst of life and death, good and evil, and love and war.

House of the Rising Sun is one of Burke’s finest novels, a literary masterpiece that bridges the author’s place in Borderland literature and Western mysteries. Readers will want to know more about the destiny and fate of his conflicted hero Hackberry Holland, whose duality of mystic-Lone Star philosopher and violent, the-ends-justify-the-means officer of the law should lead to a highly anticipated sequel to House of the Rising Sun.

—Stuart Rosebrook