— Charles Schreyvogel, “Saving the Mail” (1900), Courtesy Dickinson Research Center, National Cowboy & Western Heritage Center —

A San Antonio and San Diego Mail Line (the Jackass Mail) ad stated: “Passengers and Express matter forwarded in new coaches drawn by six mules over the entire length of our Line, excepting the Colorado Desert of 100 miles, which we cross on mule back. Passengers GUARANTEED in their tickets to ride in Coaches, excepting the 100 miles, as stated above.”

The state of various well-used wagons should have been the first clue for the boarding passengers that the ad was more fiction than truth.

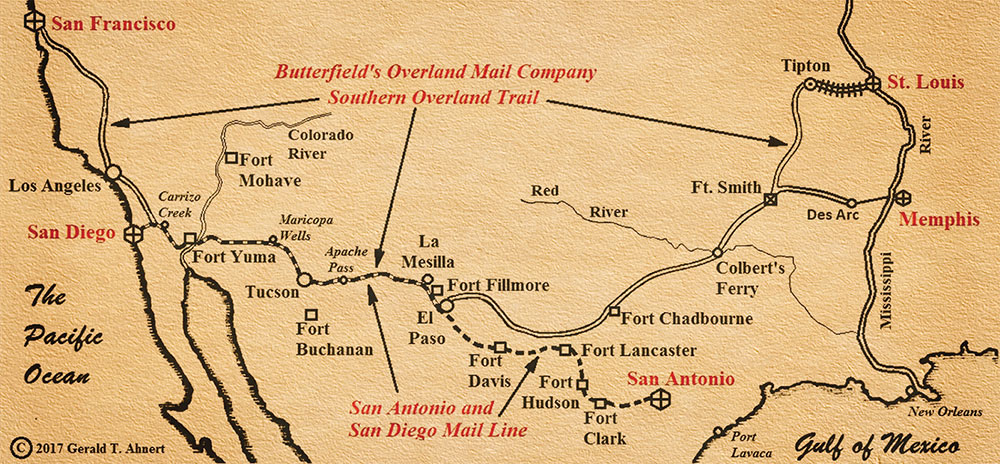

On June 12, 1857, James E. Birch, of Swansea, Massachusetts, entered into contract with the U.S. government for Route No. 8076 at $149,800 per annum, for a semi-monthly service to commence on July 1, 1857, and to expire June 30, 1861. Birch had only three weeks to organize the 1,475-mile-long trail through the frontier. He assigned Isaiah C. Woods as superintendent.

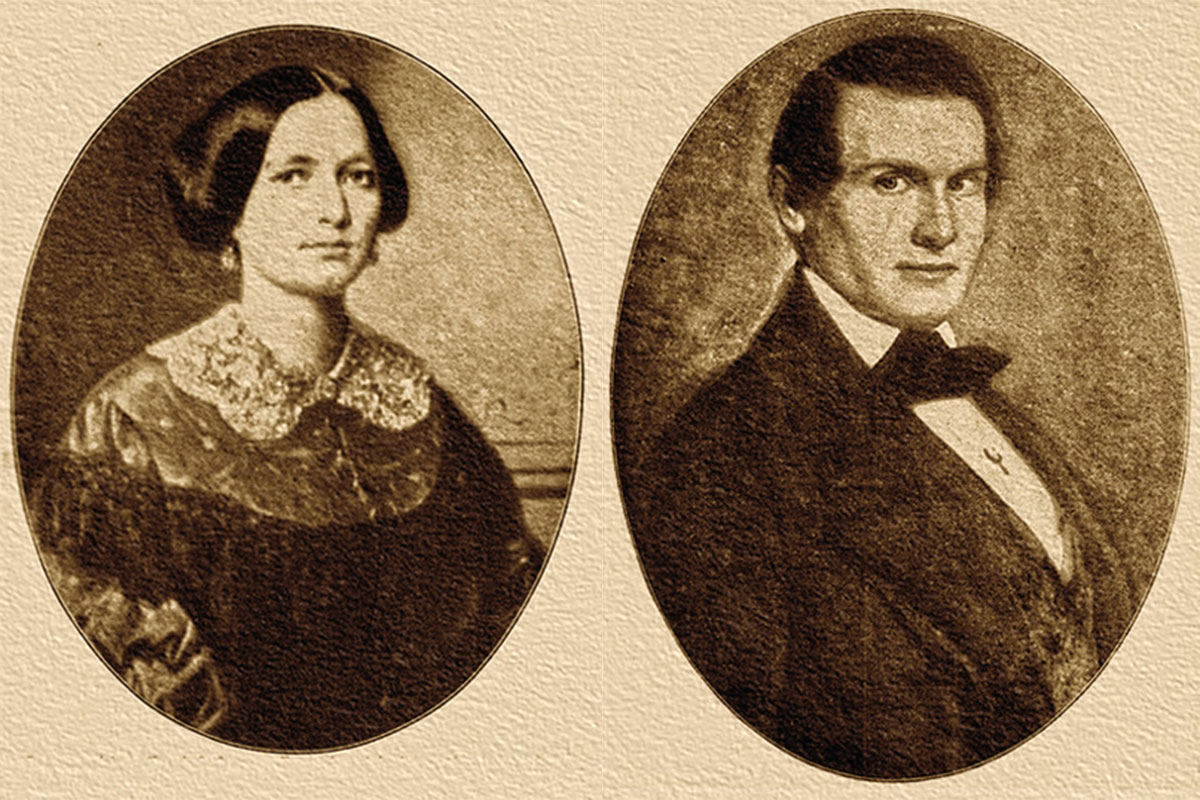

Birch’s wife, Julia, wanted a mansion filled with beautiful things with servants to care for them. Birch left Woods in charge while he returned to Swansea to finish building Julia’s mansion. On September 12 he booked passage on the ill-fated side-wheeler Central America that was laden with gold from the California goldfields. About 40 miles from Cape Hatteras, in a violent storm, the ship split her seams. Birch had refused the offer of a life-belt, and a survivor relayed Birch’s last words “No, Gabe; it’s no use,” as he strode away, smoking a cigar whose glow he fully intended should be extinguished with the last breath of his life.

In 1853-56, Birch had made a fortune from his very successful California Stage Company. He knew enough to use Concord stages, as they were known to be the best for enduring the rigors of the frontier. For his San Antonio and San Diego Mail Line, he ordered six passenger wagons from J. S. & E. A. Abbot, Concord, New Hampshire. The passengers and mail were to be transported on these well-constructed stages—but the Fates had another plan.

As soon as his wife, Julia, received word of his death, she sold all interests in the line to her half-brother Otis H. Kelton. The new stages were never put into use, as an ad in the Memphis Daily Appeal, June 25, 1858, states that five of them were for sale.

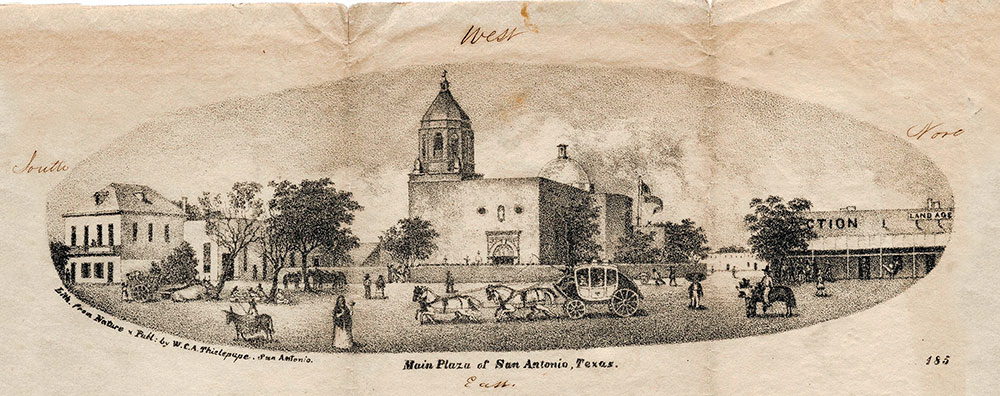

— Courtesy Gerald T. Ahnert Collection —

Kelton then sold the contract to Texan George H. Giddings, who managed the trail from San Antonio. R. E. Doyle became his partner and managed the western end of the trail from San Diego.

Superintendent Woods had a monumental job to do. In only three weeks he had to buy mules and hire personnel. Very few stations were built, and in Arizona only one crude pole-and-brush station was built at Maricopa Wells. In a letter received from Tucson by the San Francisco Herald, November 25, 1857, was the following:

“We reached the ‘Maricopa Wells,’ about 12 o’clock at night. The stage company proposes putting up an adobe house, corral, etc., at this place. At present a miserable brush house is the only shelter, and only the other day a surly Indian was seen showing his red brethren how easy it would be to send an arrow through it.”

At the beginning of the line’s service, the trail they followed was the old military road from San Antonio to El Paso, Texas. From there, they followed the Emigrant/Southern Overland Trail that zigzagged from water hole to water hole. The line left the trail and made its way through the mountains to San Diego.

Although the mail was sometimes carried by wagon, the required contract delivery time of thirty days was mostly accomplished by frontier know-how, utilizing riders on muleback familiar with the dangers of the frontier, such as Bigfoot Wallace, Henry Skillman, and Silas St. John. For this reason, the line became known as the “Jackass Mail.”

In September 1857, John Butterfield won the contract for the Overland Mail Company, and was given one year to ready his 2,700-mile-long trail for service. By the start of service in September 1858, he had significantly improved and shortened the trail and provided regularly spaced water sources, which benefited the San Antonio and San Diego Line.

The Jackass Mail had its contract as a through-mail cut short on January 1, 1859, because of the duplication of mail services with the Overland Mail Company. After that date, they carried mail from San Antonio to El Paso, Texas, and from Fort Yuma to San Diego, California. Although there was now no through-mail, the line still carried passengers on the entire length of its trail.

Superintendent Woods stated in his November 1857 report to Postmaster General A. V. Brown that: “We had seven coaches on the road….” Mostly, they were worn-out wagons that frequently broke down.

Because of the unreliability of a set schedule for the passengers on the San Antonio and San Diego Mail Line, some passengers heading west from San Antonio departed at El Paso to transfer to one of Butterfield’s more reliable Concord stage Celerity wagons. In 1859, George Foster Pierce was a passenger from San Antonio to El Paso where he transferred to a Butterfield stage. In his memoir he stated: “The stage from San Antonio runs no further than El Paso, and we had to wait two days for ‘the Overland,’ as it is called.”

— Courtesy Gerald T. Ahnert Collection —

Phocion R. Way was a passenger on the Jackass Mail in June 1858 and complained bitterly about the unreliability of the stages. He wrote in his diary:

“…3 o’clock P. M. We are now about 8 or 10 miles from Mesilla. We have stopped to feed. We took another passenger at Mesilla, which makes our whole number 5. We have also to carry feed for our mules, a large amount of baggage and the mail, which makes our load very heavy—unusually heavy. The driver is fearful that we will break down before we get through. The company should have sent another carriage but it was not done; in fact, the company have deceived us and acted shamefully from the start. They told us that the two carriages we started with would go all the way through to San Diego, and both of them have been taken from us. We left the last one at Fillmore and have an old wagon in its place. The one we have is strong and would do very well, but we should have another; it is not sufficient. The mules we have now are good, but those we have had were broken down things; and what is worse than all, they tell us now that the wagon will go no further than Tucson, and consequently those unfortunate fellows who are going through to San Diego will have to ride mule back from Tucson and keep up with the mail which is also packed on mules, and travels day and night. The poor fellows will have to travel 500 miles over a barren desert and I am afraid it is more than they can stand. It is a gross imposition that should not be born [sic] and the public should know it. They paid their money with the full understanding that they were to be taken through in an ambulance. The men employed along the line are fine fellows, and of course they are not responsible for this. This is an important route and will be much traveled, and [the] Government should see that it is properly managed.”

After arriving at Tucson, Phocion writes:

“The mail company do not run their stages farther than here, and those who paid their passage through must ride over a sandy waste on mule back and furnish the mules themselves, or stay here and get the fever and ague. This is a most rascally imposition and the company will very likely have to pay for it. If they are not compelled to pay damages, their business will be very much injured by the representations of those imposed upon. The mail company are certainly not consulting their own interests by acting this way.”

Correspondent Charles F. Huning wrote about the unreliable schedule. In the Sacramento Daily Union, March 12, 1858, he reported that after leaving San Diego they “…road [sic] on horseback that day…” After arriving at Vallecito, he wrote, “Here we met the passengers coming from the other end of the route, five in number; they complained very much, and had had a very hard time of it…” When he arrived in Tucson he wrote: “We got to Tucson, was very much disappointed at hearing that I would have to stay at that place until the return of the stage from Mesilla.” This was sometime before Christmas and later he wrote: “On New Year’s Eve, I was glad to see the coach arrive.”

Probably the most colorful account for traveling on the Jackass Mail line was given by Phocion R. Way after his arrival at Tucson:

“There is no tavern or other accommodation here for travelers, and I [was] obliged to roll myself in my blanket and sleep either in the street or in the corral, as the station house had no windows or floor and was to [sic]close and warm. The corral is where they keep the horses and mules, but I slept very comfortably as the ground was made soft by manure.”

Because the passengers didn’t know if they would travel by muleback or stage, or if they would arrive at their destination on a set time schedule, added to the difficulty of sleeping and eating along the trail meant the memory of their journey would stay with them for the rest of their lives—if they survived!

Gerald T. Ahnert of Syracuse, New York, has been interested in the Butterfield Overland Mail Company for 50 years. During the past 10 years he has focused on the colorful history of the Jackass Mail.