— All artwork and images courtesy True West Archives unless otherwise noted —

“The sheriff’s posse returned from the pursuit of the Earp party yesterday evening at 5 o’clock. The bronzed and weather-beaten appearance of the posse—more especially of Sheriff Behan and Under-Sheriff Woods—was ample proof of the arduous and exhausting nature of the trip, which had just been brought to an unsuccessful termination.”

—Tombstone Daily Nugget, April 3, 1882

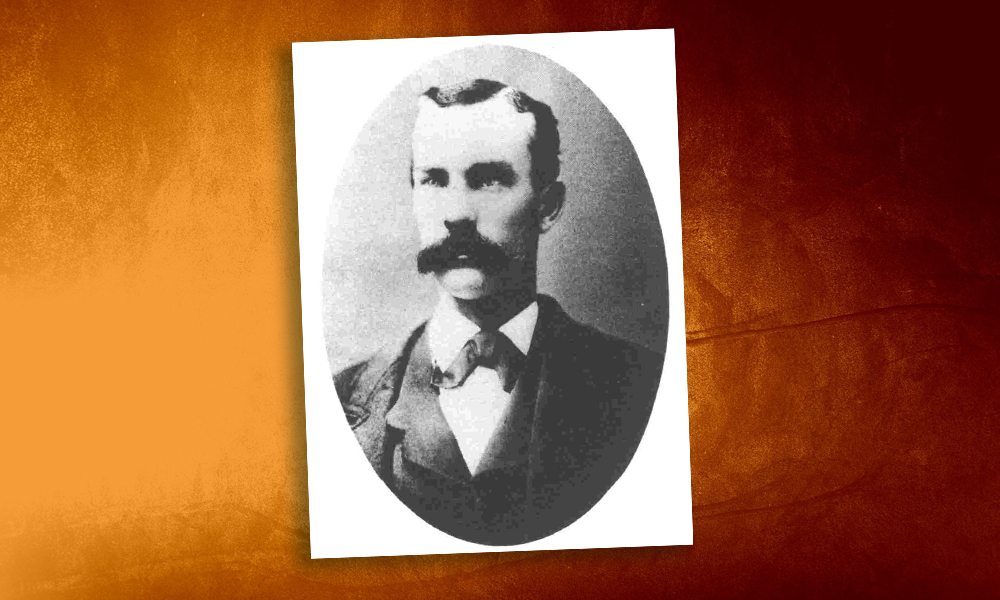

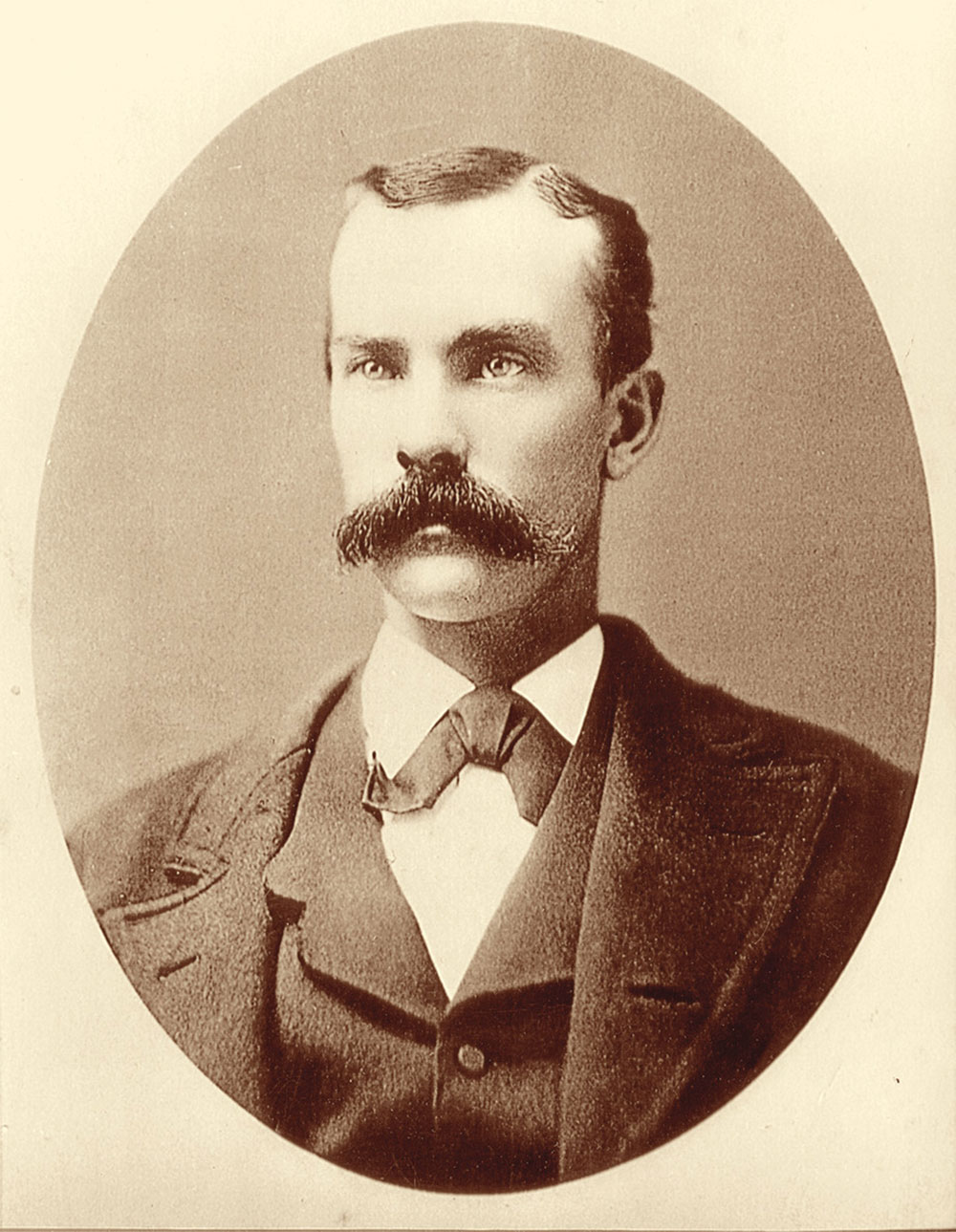

Unlike the Earps, John Ringo remained in the region to face his accusers. His…court appearance [on a robbery charge] was scheduled for May 8, and it appears likely that he visited his sisters in San Jose during April. Several notices in local newspapers confirm his absence from Tombstone during this time. On April 15 a notice of a letter for “Ringe [sic] Jno.” was published. This was followed by another notice on April 30 for “Ringold [sic] Jno.” A third notice dated May 6, for Jno. Ringold may simply have repeated the earlier April 30 listing. During his absence Apaches killed another of his old friends, Tom Redding, on April 21, 1882, along with four other teamsters.

Ringo could easily have stayed in California to avoid the possibility of prison just as the Earps did, but he was not that kind of man. Unlike Wyatt Earp, he had not run when on trial for murder, and he did not run from the larceny charges.

On May 8, 1882, the Epitaph noted, “Jack Ringo is in Town.” The same day, his attorney, Briggs Goodrich, petitioned the court for J.S. Robinson to be added as associate counsel for the defense. Ringo’s trial was set for May 12, when the cases were continued until May 13. Cause 81 was continued on May 15. Finally, on May 18, all charges were dismissed and his bail exonerated. Ringo left the courtroom a free man.

While the trial was taking place, Ringo was enumerated in Cochise County’s Great Register as entry 2649. The registration on May 16 listed him as a speculator. It incorrectly gave his residence as Tombstone and his age as 39. He had barely turned 32.

Ringo returned to New Mexico. One of those happy to see him there was Mary Hughes, a younger sister of Jim Hughes.

John Ringo was an especially welcome guest at the Hughes home. He was the hero of 11-year-old Mary Hughes. Whenever Mary, scanning the country from the watchtower, saw him coming, she put on her prettiest dress and combed her glossy, black hair. John Ringo, when he spoke to her, made her feel like a great lady. He had read many books, and he told her of what he read. So he taught her English from the family Bible, and Spanish from a book he had picked up in Tombstone. He taught her how to write, and she took enormous pride in copying his beautiful Spencerian chirography.

Ringo had now reached the pinnacle of his fame. His reputation remained intact, and he was well thought of by most of his contemporaries. At the same time he was still suffering from whatever darkness plagued him, and his efforts to blot it out led him to ever-heavier drinking that deepened his depression and caused him to drink more. It was a vicious circle.

In late June or early July he returned to Tombstone, where he was reportedly on an “extended jamboree.” On July 2 he confided to an Epitaph reporter “he was as certain of being killed, as he was of being living then. He said he might run along for a couple of years more, and may not last two days.”

Ringo left Tombstone on July 8, arriving at “Dial’s in the South Pass of the Dragoons.” From Dial’s he rode on to Galeyville, where he continued drinking. Tombstone deputy Billy Breakenridge ran into him along the road. He wrote:

“… I met John Ringo in the South Pass of the Dragoon Mountains. It was shortly after noon. Ringo was very drunk, reeling in the saddle, and said he was going to Galeyville. It was in the summer and a very hot day. He offered me a drink out of a bottle half-full of whiskey, and he had another full bottle. I tasted it and it was too hot to drink. It burned my lips. Knowing that he would have to ride nearly all night before he could reach Galeyville, I tried to get him to go back with me to the Goodrich Ranch and wait until after sundown, but he was stubborn and went on his way.”

The following day Ringo was found dead in Morse’s Canyon. The Epitaph published a long obituary noting in part that:

He was recognized by friends and foes alike as a recklessly brave man, who would go any distance, or undergo any hardship to serve a friend or punish an enemy. While undoubtedly reckless, he was far from being a desperado and we know of no murder being laid to his charge. Friends and foes are unanimous in the opinion that he was a strictly honorable man in all his dealings, and that his word was as good as his bond. He was found by a man named John Yost [sic] who was acquainted with him for years both in this Territory and Texas.

Ringo had shot himself in the head. In New Mexico the papers also noted his death:

Another Great Soul Flown

It is with much regret that we chronicle the demise of one of the most illustrious men of the southwest. Had the much lamented deceased lived in antiquity his fame might have surpassed that of Hector or Ulysses; but alas, republics are ungrateful, and no public honor was ever shown to the king of the cowboys. Born of poor but honest parents, John Ringgold surmounted all the obstacles thrown in his path and made for himself a name that should live in the history of the nation. Gentleman like and pleasant in his manner, even easy going in many ways, he was a rigid observer of the old fashioned frontier code of honor that unfortunately is fast disappearing. During the past few years thirty-two men dared to doubt his honor. They now fill thirty-two graves. He distinguished himself when at Shakespeare by his fine and effective shooting, and is kindly remembered in that burg. Although he had many competitors in his line, he had no true rivals, and Curly Bill and Billy the Kid will not bear comparison with him. His body was found last week in the Chiricahua mountains with a bullet hole through the head. The supposition is that he was crossed in love and ended his sufferings in this tragic manner. Thus passed away in the flower of his youth a man who, had he lived, might have aspired to almost any eminent position. Alas! ’twas not to be:

Car il etait du monde ou les plus belles choses

Ont le pire destin.

Et Ringgold a vecu ce que vivent les roses L’espace d’un matin.

The poem translates as:

For he was of the world in which the most beautiful things

Have the worst destiny,

And Ringgold lived as live the roses

The duration of a morning.

Other accounts noted his passing, but these two provided by the contemporaries who knew him best clearly indicate the sense of loss felt by the community.

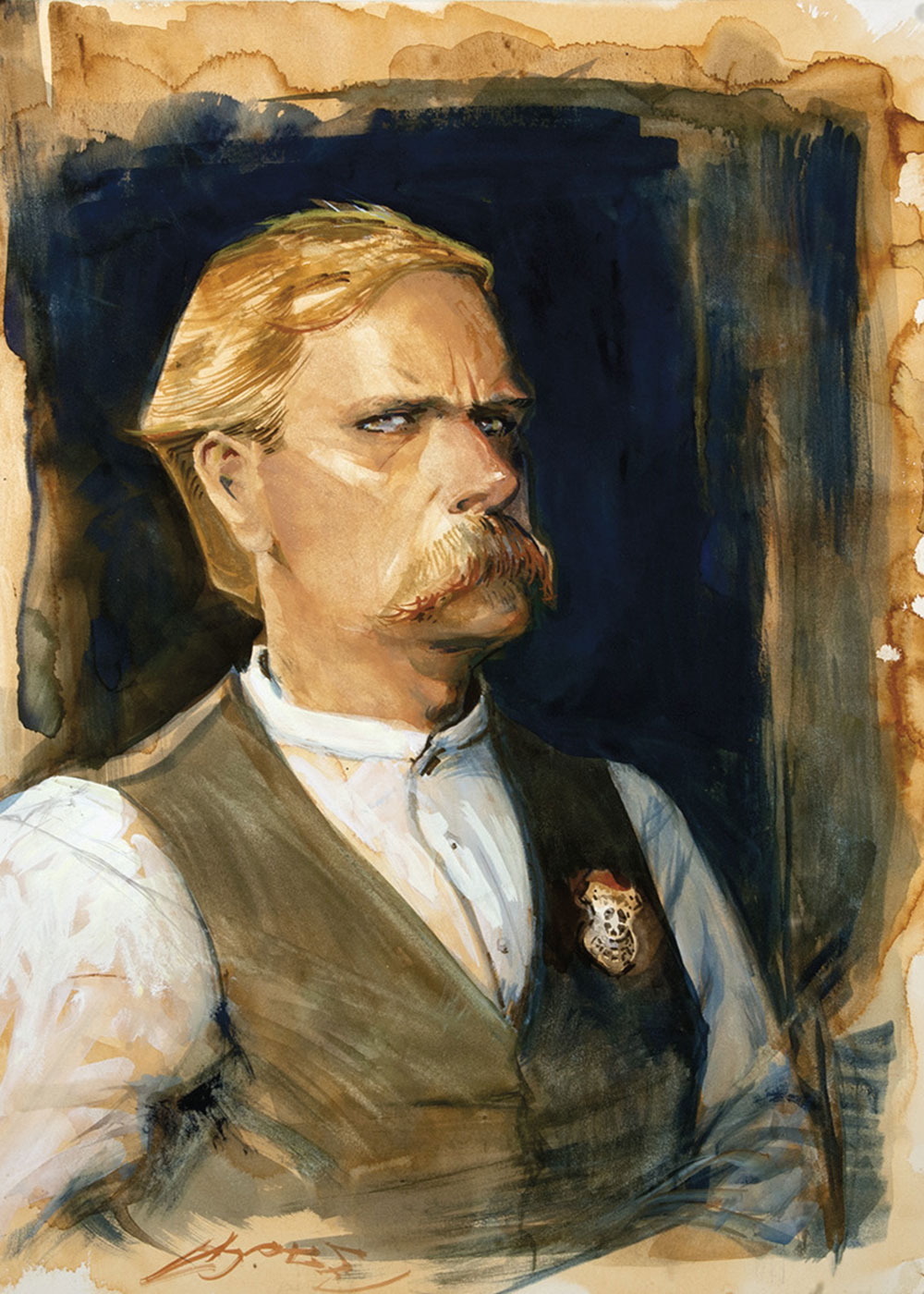

Ringo’s death remains controversial. Since his demise in 1882, many have denied that Ringo killed himself and advanced numerous men as the assassin. One popular theory is that Wyatt Earp returned to Arizona to kill Ringo. This has led to elaborate scenarios where Wyatt and a party of men waited until Ringo was roaring drunk and killed him. Among the various others blamed for murdering Ringo have been Doc Holliday and Buckskin Frank Leslie.

Ringo biographer Jack Burrows opts for suicide. He quotes a letter from Charles Ringo to William K. Hall that states in part, “I have another story from a Mrs. Travis whose husband was of that family, that the sisters would not let him in the house. You will notice that the body was left in Arizona and not brought back.” Based upon that and other correspondence from Charles Ringo, he concludes that Ringo had attempted to return to his family but met a hostile reception and despondently went back to Arizona, where he killed himself. Another states, “John Ringo had lost all interest in life, and in a state of alcoholic despair the young man shot himself.”

Seeking to prove that his family had disowned Ringo, one writer references letters Ringo received from his family and quotes Frank Cushing, John’s nephew, as stating that he never wrote back. This is intriguing, for if John did not write to his family, how did they know where to write to him once he left Missouri in the early 1870s? Moreover, if his family disowned him, why was he found with a letter from Fanny Jackson in his pocket? The Citizen stated, “In one of the pockets [of his coat] were three photographs and a card bearing the name Mrs. Jackson.”

The statement made for the coroner has also provoked controversy, both for what it did and did not say. The points of contention may be summarized as its failure to mention that a bullet had been fired from the pistol, its failure to mention powder burns, and its description of “a bullet hole in the right temple, the bullet coming out of the top of the head on the left side. There is apparently a part of the scalp gone including a small portion of the forehead and part of the hair. This looks as if cut out by a knife.”

The weaknesses in the statement can be explained in part by the backgrounds of the 15 witnesses. None of them were physicians, and the coroner was not present. They were describing what they saw as accurately as they could for the coroner. Concerning their failure to mention the discharged weapon, Ringo’s obituary in the Tucson papers provided some additional information: “The pistol with one chamber emptied [emphasis added] was found in his clenched fist.” Such papers as the Phoenix Gazette and the Citizen picked up that news release. The Phoenix Gazette noted:

“John Ringgold, one of the best known men in southwestern Arizona, was found dead in Morse’s canyon, the Chiricahua mountains last Friday. He evidently committed suicide. He was known in this section as “King of the Cowboys” and was fearless in the extreme. He had many staunch friends and bitter enemies. The pistol, with one chamber emptied, was found in his clenched fist. He shot himself in the head, the bullet entering on the right side, between the eye and ear, and coming out on top of the head. Some members of his family reside at San Jose California.”

Witness Robert M. Boller also confirmed that Ringo’s pistol had been fired. “His pistol with one empty shell was caught in his watch chain.” The failure to mention the discharged shell was simply that, a failure, which was corrected when the weapon was examined later.

The report’s failure to mention powder burns could have resulted from either of two possible causes. First, as with the cartridge, the untrained observers might simply have overlooked any powder burns. Second, by the time Yoast found Ringo, the body was decaying in Arizona’s summer heat. Boller recalled the “body was in such condition that we buried it right there.” In another letter he provided more graphic details. Responding to Frank King’s inquiry “if I noticed powder marks on Ringo’s head” Boller wrote, “The body had turned black and was smelling.” Boller further added:

“He had held the six-shooter against his head about an inch above his right ear and pulled the trigger. That is the way we all agreed that it happened except John Yoast, and he too was convinced when I showed him where the bullet had entered the tree on his left side. Blood and brains oozed from the wound and matted his hair. There was an empty shell in the six-shooter and the hammer was on that.

Despite the strange exit wound, the men who found Ringo never doubted that he had killed himself. “[A. E.] ‘Bull’ Lewis, who was in the coroner’s jury told me there was absolutely no question but what Ringo committed suicide,” Boller recalled. “There is no question in the minds of any of the five [sic] who found him but what [he] committed suicide.”

Ringo’s horse wandered until July 25. “Smith,” says the Tombstone Independent, “found John Ringo’s horse, on Tuesday last, about two miles from where the deceased was found. His saddle was still upon him with Ringo’s coat upon the back of it. In one of the pockets were three photographs and a card bearing the name of ‘Mrs. Jackson.’ It seems strange that the horse should have wandered about all this time without having been discovered before. Mr. Smith brought the horse into town with him. It is a bay, weighing about 1,000 pounds.”

Why Ringo committed suicide is unknown and will likely remain so. It could be for reasons as complex as post-traumatic stress syndrome or simple depression exacerbated by alcohol. It could have been that a spur of the moment depression induced the impulse. Whatever the cause, all that is known for certain is that John Ringo killed himself at around three o’clock in the afternoon on July 13, 1882. His journey into folklore had begun.

The Legend of Ringo

For more than a century, John Ringo successfully eluded serious biographers. Never reluctant to let facts interfere with a good story, pulp writers and folklorists either invented or repeated settings and events that, given the dearth of factual evidence available, at times had the ring of truth. There is a copious amount of these fictions beginning in the 1920s and persisting to the present.

In the years following his death, John Ringo has fascinated readers. Historian Steve Gatto notes Ringo’s legend “began to slowly sprout and take root” only four days after his death. The seeds of that legend were sown in Texas’s bitter Hoo Doo War. At the time he was no different from dozens of other men engaged in the conflict, each with his own story. Yet unlike most of them, Ringo was destined to become a legend.

Walter Noble Burns can be credited with almost single-handedly popularizing John Ringo. From his pen emerged a tarnished knight errant who rode out of nowhere and died mysteriously. In 1927 Burns wrote, “John Ringo stalks through the stories of old Tombstone days like a Hamlet among outlaws, an introspective, tragic figure darkly handsome, splendidly brave, a man born for better things, who, having thrown his life recklessly away, drowned his memories in cards and drink and drifted without definite purpose or destination.” With that single, emotional sentence, Burns set the stage for the romantic myth of John Ringo.

Unfortunately for history, Burns allowed his desire to write a marketable book interfere with historic truth. Tombstone, An Iliad of the Southwest mingled folklore with fact to the point that the entire volume is suspect. One writer characterizes the book as “seriously flawed. When Walter Noble Burns wrote Tombstone in the style of his time, the question followed: Is this history or is it a novel?” In creating the mythical John Ringo, Burns also created a target for later historians and writers to either assail or glorify.

Ringo was far more than a creation of Burns, however. In the pre-Tombstone

gunfighting West he was recognized and respected. John Wesley Hardin, Texas’s number one shootist, made Ringo’s acquaintance in the Travis County jail in Austin. Hardin apparently liked the man. William Preston Longley, a gunman of equal notoriety, also knew Ringo but disliked him. Any number of men tried to enhance their own reputations by boasting that they killed Ringo while he was passed out from a binge lasting several days. Little glory attaches itself to killing a sleeping man, and the historian must ask why so many have made the claim.

Part of the answer lies in Ringo’s Texas years. He fought in the Hoo Doo War and arrived in Arizona with garbled accounts of that feud yapping at his heels. In his abbreviated account of the feud, Burns confused Ringo’s actions with those of fellow feudist John Baird: “While he was little more than a boy, he became involved in a war between sheep and cattle men. His only brother was killed in the feud, and Ringo hunted down the three murderers and killed them.” Burns doubtless drew that succinct and oversimplified version from one of his informants. It was what people in Arizona believed and, inaccurate as it was, Ringo could not escape his reputation. He was the feudist who destroyed his enemies, the remorseless gunman who killed savagely and emerged unscathed. In contrast, the men who knew Ringo generally liked him. Grace McCool, who interviewed Ringo’s acquaintances, asserted, “All the old-timers who knew him, liked him, and spoke well of him.”

Epilogue

John Ringo remains today as Burns described him, a tragic figure. From his youth, death stalked his family. His efforts to help them drew him into the violence of the Hoo Doo War and, later, into the notoriety of Tombstone. He has been branded a cattle thief—a charge for which not a single indictment has been located. Since his suicide in 1882 his family has been victimized, first by Allen Erwin and later by other writers who have further tarnished their names. Others such as George Upshur, inspired by Lake’s work, recalled him as “the best and most powerful of all the cowboy gang leaders.” In the end we are left with the recollections of those contemporaries who knew him best. “Friends and foes are unanimous in the opinion that he was a strictly honorable man in his dealings, and that his word was as good as his bond.”

It is a fitting epitaph for a man.

“Death of a Cowboy, Birth of a Legend” is excerpted from John Ringo, King of the Cowboys: His Life and Times from the Hoo Doo War to Tombstone, 2nd Edition, by David Johnson, Foreword by Chuck Parsons (University of North Texas Press).