The true story of how the trailblazer became the spearpoint of empire

All Images Courtesy True West Archives Unless Otherwise Noted

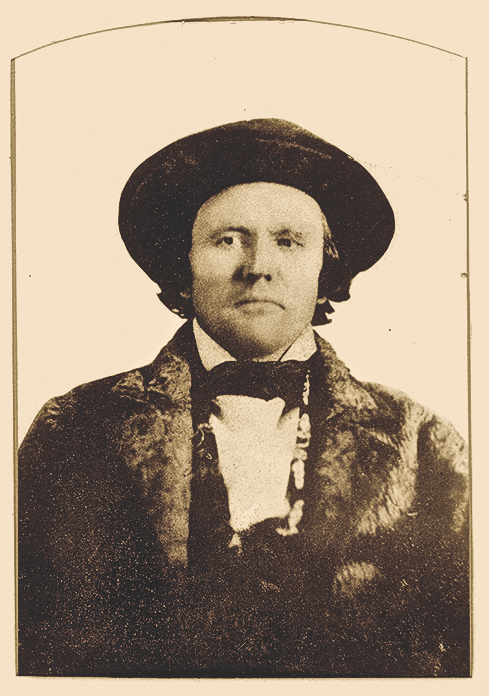

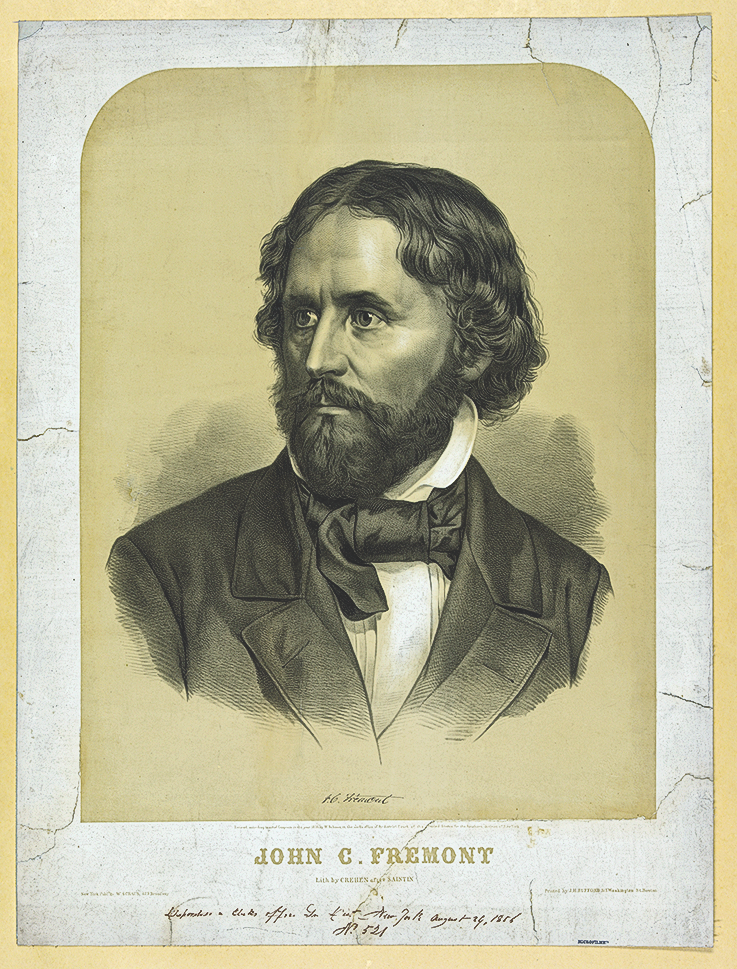

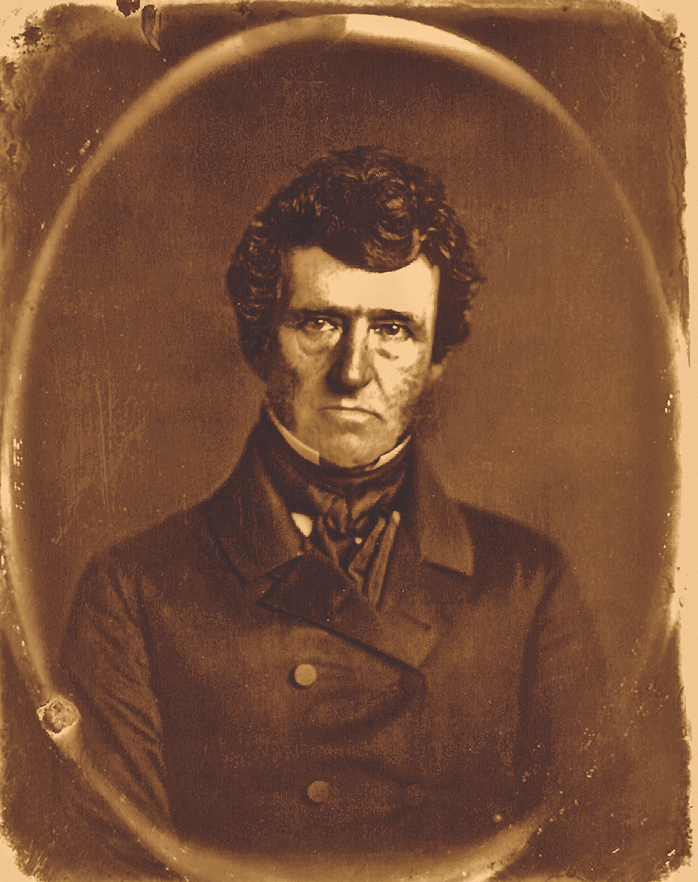

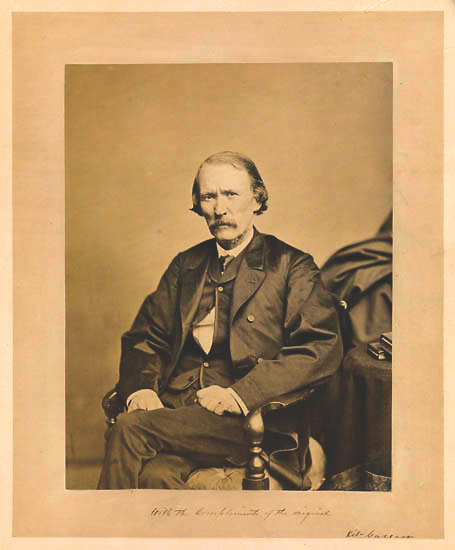

Kit Carson wanted to settle down. “Dick Owens and I concluded that, as we had rambled enough,” he later recalled, “it would be advisable for us to go and settle a farm.” Since leaving the mountains in 1841 with the collapse of the beaver trade, he had twice guided the Army explorer John C. Fremont westward. Carson had taken Fremont through South Pass to map the Oregon Trail in 1842 and then had served as scout and hunter for the far more ambitious expedition to Oregon and California the following year. Fremont’s reports of these expeditions, partially ghost-written by his beautiful and talented wife, Jessie Benton Fremont, had become a national sensation. Ten thousand copies were printed at government expense, thanks to Jessie’s father, the powerful Missouri Senator Thomas Hart Benton. The books, which became emigrant guides to the West, made Fremont the “Pathfinder”—and his redoubtable scout Carson—into national celebrities.

His new fame mattered little to Carson. On February 6, 1843, he had married Maria Josefa Jaramillo in Taos, New Mexico, and was anxious to make a new life with her. They settled some 45 miles east of Taos on the Little Cimarron, where Carson and Owens cut timber for cabins and put in considerable grain. In August a messenger from Bent’s Fort reached the little ranch with news that Fremont wanted Carson for yet another expedition. Carson had promised Fremont that he would join him if needed for another “exploration,” and so he and Owens sold their improvements at quite a loss and, after leaving Josefa with her sister’s family in Taos, headed north.

Fremont was elated: “This was like Carson, prompt, self-sacrificing, and true. I received them both with great satisfaction. That Owens was a good man it is enough to say that he and Carson were friends. Cool, brave, and of good judgment; a good hunter and good shot; experienced in mountain life; he was an acquisition and proved valuable throughout the campaign.”

Fremont’s party, 60 in number, departed Bent’s Fort on August 16, 1845, driving two hundred horses and mules as well as a small herd of cattle. This was an experienced and hardened band, consisting of seasoned frontiersmen, many of whom had served with Fremont before. Lucien Maxwell was there, along with Auguste Archcambeau, Bill Williams, Basil Lajeunesse, Joseph Reddeford Walker, Theodore Talbot, Tom Fitzpatrick and the always reliable Alexander Godey. A dozen Delaware Indians, led by their chiefs Swanuck and Segundai, formed Fremont’s personal bodyguard. It was a formidable crew.

guide Kit Carson

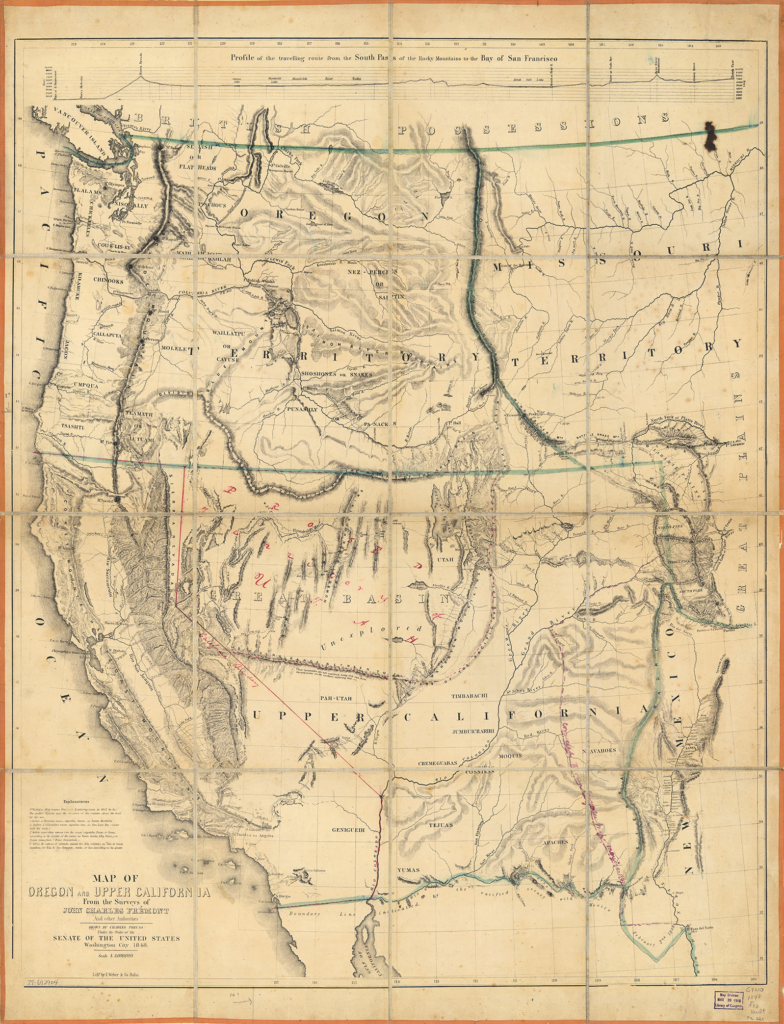

The Survey

Fremont’s orders directed him to explore and map the Arkansas and Red rivers, to pay special attention to the headwaters of the Arkansas, as well as to explore the southern Rockies. Nowhere in the written orders was there mention of California. Fremont clearly must have had verbal instructions to proceed to California, for he promptly detached Lt. James Abert and Tom Fitzpatrick to explore south through Raton Pass to the headwaters of the Canadian River and then east to its junction with the Arkansas in partial fulfillment of his orders from the topographical corps. He then proceeded westward, ascending the Arkansas toward the towering Rocky Mountains.

In the December 27, 1845, issue of New York Morning News, journalist John L. O’Sullivan had perfectly captured the national mood when he editorialized on the American need to annex both Texas and Oregon “by right of our manifest destiny to overspread and to possess the whole of the continent which Providence has given us for the development of the great experiment of liberty and federated self-government entrusted to us.” Manifest Destiny quickly became the catch-phrase of the day. It was hardly a new doctrine, dating back to the Puritan fathers and their “city upon a hill” and up through Thomas Jefferson’s dream of a continental “empire for liberty.” Expansionist sentiment had helped to bring on the War of 1812. This combination of expansionism and nationalism, with the added benediction of divine providence, reached its aggressive climax in the 1840s.

War with Mexico

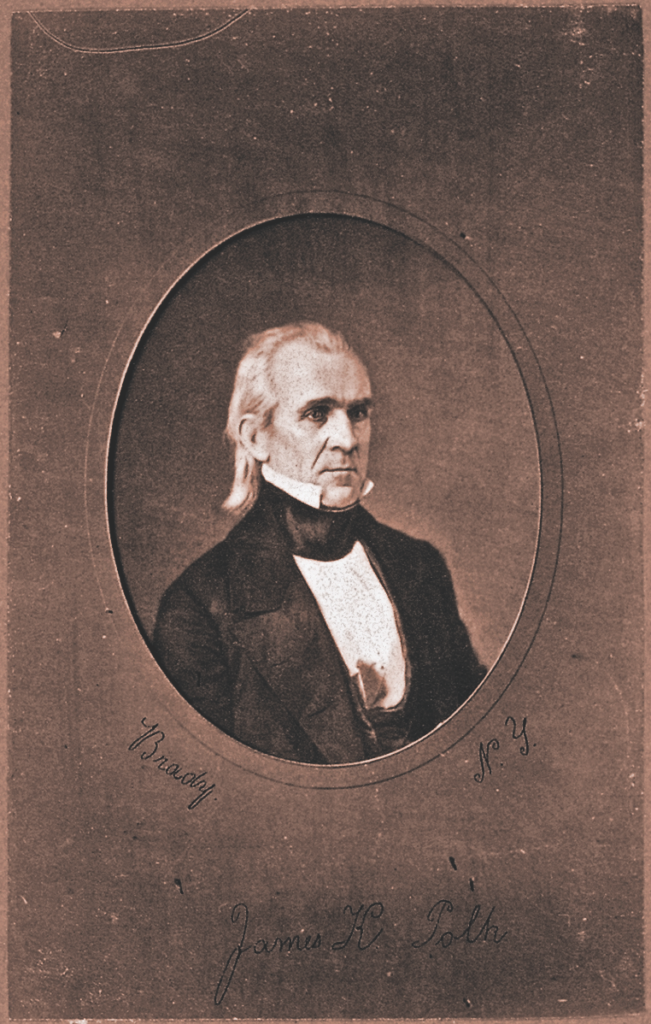

James K. Polk was a firm disciple of Manifest Destiny. The new president had campaigned on an expansionist platform calling for the annexation of Texas and the Oregon country (“Fifty-four Forty or Fight” was the slogan). He was determined to purchase New Mexico and California, or to fight a war for them if need be. Polk and his Secretary of the Navy, the noted historian George Bancroft, fretted over the intentions of England concerning California. Mexico had threatened to declare war if Texas was annexed, and Polk and Bancroft worried that the British would seize the prized harbor at San Francisco Bay if war broke out.

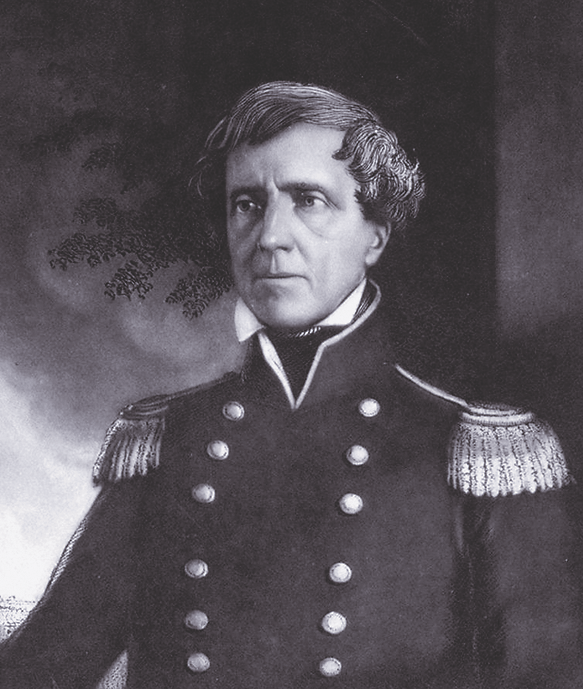

On March 21, 1845, Bancroft sent orders to Commodore John Sloat, commander of the Pacific Squadron, to proceed to the west coast of Mexico and then ordered him to promptly seize San Francisco Bay if he heard of a declaration of war. With Texas annexed in December 1845, Polk ordered 3,500 troops under Gen. Zachary Taylor to Corpus Christi Bay. When Mexican troops marched north to the Rio Grande, Taylor moved his troops south into the disputed Nueces strip. The two armies warily watched each other for three tense months. Finally, Gen. Mariano Arista took the bait and sent a detachment across the Rio Grande where they ambushed an American troop detachment, killing several men.

President Polk had been working on a war message to Congress—as a result of Mexico’s refusal to pay its debts to the United States or to consider his generous offer to purchase New Mexico and California—when news of the Rio Grande skirmish reached him on May 9, 1846. He hurriedly revised his message: “Now, after reiterated menaces Mexico has passed the boundary of the United States, has invaded our territory and shed American blood upon the American soil.” Two days later Congress declared that “by the Act of the Republic of Mexico a state of war exists” and authorized President Polk to raise an army of 50,000 men.

Westward to California

Fremont knew nothing of any of this when he decided to extend his exploration westward beyond the Great Basin and over the Sierras into California. He divided his force in late November, sending Theodore Talbot, with Joe Walker as guide, south along the eastern Sierra foothills to cross the mountains at a pass Walker had discovered a decade before and enter the San Joaquin Valley. He and Carson, with 15 men, would follow the Truckee River over the mountains at a place soon to be known as Donner Pass and then down to the south fork of the American River. Fremont’s party reached Sutter’s Fort on December 10, 1845.

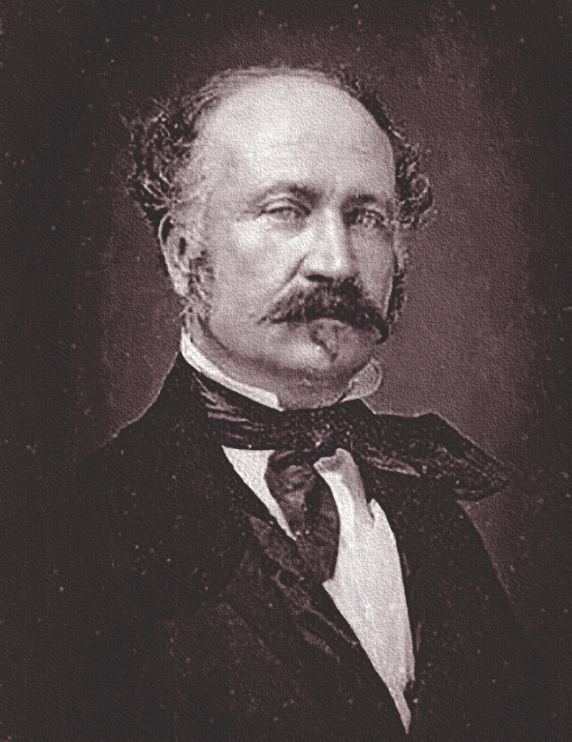

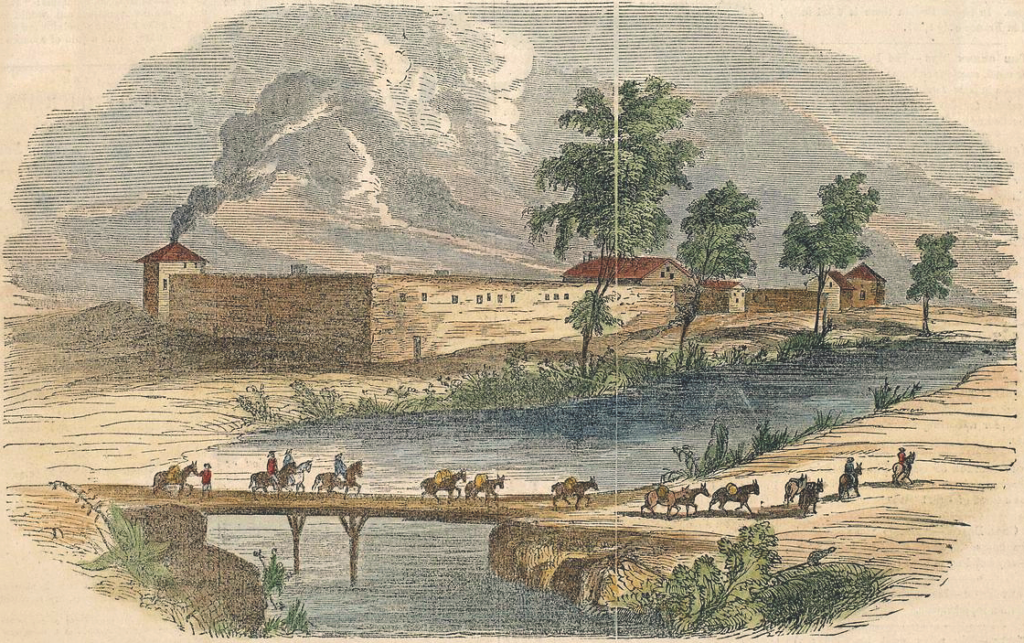

John Sutter, although born in Baden, Germany, was of Swiss descent. He had come to America in 1834, settled in St. Louis and was soon engaged in the Santa Fe trade. Four years later he arrived at San Francisco Bay where he became a Mexican citizen. Blessed with considerable charm and some financial resources and business savvy, he quickly ingratiated himself with the Mexican authorities. The governor granted him nearly 50,000 acres in the Sacramento Valley where he had constructed a substantial mud and brick fort as the headquarters of what he christened as “New Helvetia.” He also purchased Fort Ross from the Russian-American Fur Company and then moved its goods, livestock and cannons to the Sacramento Valley. Sutter soon employed hundreds of Indian, Mexican and American workers.

Fremont felt certain that Sutter, who had extended his hospitality to him 18 months earlier during the explorer’s second expedition, would again warmly greet him. They had discussed the future of California back in 1844, so Fremont knew that Sutter welcomed American emigrants and shared the captain’s dream of an American California. Still, Sutter was in a delicate position and needed to carefully balance his relationship with the Army captain and his Mexican benefactors.

Rumors of war over Texas were rife, and the 800 Americans in California were viewed with suspicion. The Californios outnumbered them 10 to one but they were bitterly divided north and south. (The Indians, although but a pitiful remnant of the vast population that had existed when the Spanish first arrived in 1542, outnumbered both groups by several thousand.) General Jose Castro in Monterey ruled over the north while Governor Pio Pico, headquartered in Los Angeles, was the power in the south. The two men disliked each other intensely but agreed on their mutual disdain for the government in Mexico. They both acted independently of the central government.

Sutter was absent when Fremont first arrived but returned in a few days to extend his hospitality to the newly arrived Americans. Fremont needed mules and cattle, which Sutter provided. Fremont explored the countryside, met with settlers, skirmished with some local Indians, and fretted over Talbot’s party. It soon became abundantly clear to the 31-year-old captain that California was not only exceedingly ripe fruit, but it was quite low hanging as well. In January, Fremont crossed the San Joaquin Valley to Yerba Buena and gazed in amazement at the wide opening in the Coast Range where the San Francisco Bay met the Pacific Ocean. He named it the Golden Gate. They then rode south to Monterey to meet with the American consul Thomas Larkin. The consul took Fremont to meet General Castro who was quite cordial but advised Fremont to stay away from the coastal towns and remain in the interior. The American officer assured Castro that his peaceful party was solely devoted to mapmaking.

Fremont and his men then traveled some 60 miles north to San Jose, where they were reunited with the Talbot and Walker party. They then moved back south to Monterey. Sixty heavily armed Americans approaching his provincial capital naturally worried General Castro, who sent an order to them to promptly depart California. Then the general issued a call to arms to the Californios on March 8, in order “to lance the ulcer which (should it not be done) would destroy our liberties and independence.” On that very same day, in Texas, General Taylor had moved his army across the Nueces River into the disputed land north of the Rio Grande.

Fremont moved his force northeast of Monterey to Gavilan Peak in the Coast Range, where the men commenced to build a rude log fort. Fremont hoisted the American flag and prepared to fight. Larkin sent a message to Fremont urging restraint and warning of the mobilization of a large Mexican force. Fremont responded with a note of romantic bravado reminiscent of Travis at the Alamo: “We have in no wise done wrong to the people or authorities of the country, and if we are hemmed in and assaulted, we will die every man of us, under the Flag of our country.”

Rhetoric aside, Fremont now began to think that discretion might well be the better part of valor—and that as a junior officer he probably should not initiate a war between the United States and Mexico. When a breeze blew over the impoverished flagpole on March 9, Fremont took it as an omen and ordered his men to prepare to move out under cover of darkness. Joe Walker was furious over what he felt was a cowardly retreat. As Fremont’s party headed north, Walker headed south. The Mexicans did not pursue.

Courtesy Huntington Digital Library

Retreat to Oregon

Fremont’s party leisurely moved north past Mount Shasta to reach Oregon’s Klamath Lake on May 6. They were met there by Klamath Indians who traded dried fish and salmon with the newcomers. The Indians were friendly but wary. Fremont led his men farther north between the lake and the mountains and on the night of May 8 camped in a forest on a little creek not far from the lake. Standing alone by the campfire, Fremont was startled to hear the muffled sound of approaching horse hooves. Two exhausted men emerged from the shadows into the firelight with a remarkable tale to tell. Fremont instantly recognized Sam Neal, who had been with him on his second expedition before settling in California. Reinforced with hot coffee, Neal told Fremont that he had been sent forward by Lt. Archibald Gillespie of the United States Marines, who was in search of the explorer with important dispatches from Washington. The men had been trailed by Indians and were worried for the safety of Gillespie and his three other companions camped south of Upper Klamath Lake. Fremont decided to leave at dawn with 10 hand-picked men to make up a rescue party—Carson, Owens, Godey, Maxwell, Joe Steppefeldt (called Stepp), Basil Lajennesse, Segundai, Denny (an Iowa mixed blood) and two other Delawares.

The next day they found Gillespie camped some 40 miles away at the lower end of the lake. The young Marine officer had travelled from Washington across Mexico and then by ship to Monterey. President Polk had sent him on this dangerous secret mission with messages for Larkin and Fremont. Fearing that he might be intercepted in Mexico he had memorized Polk’s written instructions and then burned the originals, but he did carry letters to Fremont from Jessie and Senator Benton. The message and the Marine officer’s own observations in Mexico made it clear that war was imminent. (They did not know it, but the war had already begun on the Rio Grande.) Polk and Benton were worried about British intentions over California and wanted Fremont to be ready to claim the province for the U.S. the instant he heard of a war declaration.

The two officers talked well into the evening, making plans, and were only interrupted by the arrival of several Klamath Indians bearing salmon. The Klamath chief handed a fine fish to Gillespie and then led his men out of the camp. As the men settled into their blankets, Fremont stayed up pondering his next move. He felt himself but a pawn in a grand chess game, but as a pawn he must make the first move. “I saw the way opening clear before me,” he later wrote. “This decision was the first step in the conquest of California.”

Carson heard them first. “What the matter over there!” he called out to Lejeunnese. Then he heard the sickening sound of an axe striking flesh and shouted the alarm: “Indians!” Crane, one of the Delawares, jumped to his feet but his rifle misfired, and he was instantly struck by four arrows. Carson, Steppenfeldt and Maxwell all fired, and the Klamath chief went down.

Godey stepped into the light of the campfire to check his firearm. This astonished Carson who yelled out “Look at the fool. Look at him, will you?” Godey gave Carson a dirty look and continued to tinker with his rifle as arrows whizzed by. “He was the most thoroughly insensible to danger of all the brave men I have known,” remarked Fremont.

The Indians withdrew and the men lay under cover all night. At dawn the gray light revealed that Lajeunesse, whose head had been bashed in with an axe; Crane, the Delaware; and Denny were dead and another of the Delawares wounded. The Klamath chief who the day before had given Gillespie salmon lay dead by the smoldering campfire.

“He was the bravest Indian I ever saw,” Carson remarked. “If his men had been as brave as himself, we surely would all have been killed.” The chief had a British axe tied to his wrist. Carson took the axe and knocked the chief’s head to pieces after Sagundai scalped him.

Fremont, who suspected that the British had incited the Klamaths, was now determined on revenge. Once the command was reunited Carson went ahead with 10 men and promptly found and attacked a Klamath village of 50 lodges, scattered the people, and set everything on fire.

Fremont brought the rest of his men up to reinforce Carson, but the Klamaths had all fled from the burning village. About a mile from the village, he made camp and had the men build a strong corral. Word soon reached the camp that the Klamaths were returning, and the men hurriedly mounted. Fremont and Carson led them out into the thick forest where Fremont’s horse, a gift from Sutter named Sacramento, made a daring leap over a fallen oak.

“Captain, that horse will break your neck someday,” Carson shouted.

Minutes later a Klamath scout emerged from behind the trees and drew a bead on Carson with his bow. Carson fired at him but his rifle snapped. Fremont spurred Sacramento and they rode the Indian down so that his arrow shot went wild. Sagundai then leapt upon the Klamath and smashed in his skull with his war club. It was all over in a moment, but it was a close call for Carson, who now developed a keen appreciation for Sacramento. “I owe my life to them two,” declared Carson. “The colonel and Sacramento saved me.”

“By heaven, this is rough work,” Gillespie exclaimed. This was the first combat he had witnessed since joining the Marines. He would soon see much more.

The Revolt Begins

Fremont’s party reached Peter Lassen’s ranch in the Sacramento Valley on May 24 after skirmishing with Indians during much of the journey south. Fremont found the American settlers in an uproar over a decree from Castro threatening all non-Mexican citizens with expulsion and by recent raids by Indians from the nearby hills. Some of these raiders were descendants of mission Indians who had retreated to the mountains rather than work as serfs for Sutter or the Mexican ranchers. Others were Maidus, Wintus and Yanas who had lived in the Sacramento Valley long before the Spanish first arrived. They numbered several thousand and sometimes raided the American and Mexican ranches for livestock.

Fremont was reluctant to lead a campaign against them but relented to the settlers’ pleas when he received a message from Sutter warning that Castro had sent messengers to incite the Indians against the American settlers. “I resolved to anticipate the Indians and strike them a blow which would make them recognize that Castro was far and that I was near.” He convinced himself that it would be unwise to leave a potentially hostile force to his rear. Fremont’s combined army of settlers and his own men struck several rancherias along the Sacramento River, killing dozens of the Natives and driving the rest into the hills. While the Indians were numerous, they were poorly armed, and it was over quickly. This one-sided affair disturbed Carson. “The number killed I cannot say,” he declared. “It was a perfect butchery.”

With the Indians neutralized Fremont turned his attention to the Californios. He encouraged Ezekiel Merritt, William Fallon and William Ide with 30 American settlers to capture the Mexican garrison and cannons at Sonoma, the northern-

most settlement. The Americans found no Mexican soldiers and the town’s nine brass cannon were hardly serviceable, but they did capture Gen. Mariano Vallejo and 17 Sonoma residents. Vallejo, who was sympathetic to the American annexation of California, offered his captors some brandy and his sword. They let him keep his sword but readily drank all the brandy. Vallejo and his compatriots were taken to Sutter’s Fort and imprisoned. When Sutter objected to this, Fremont seized the fort and put Edward Kern in command.

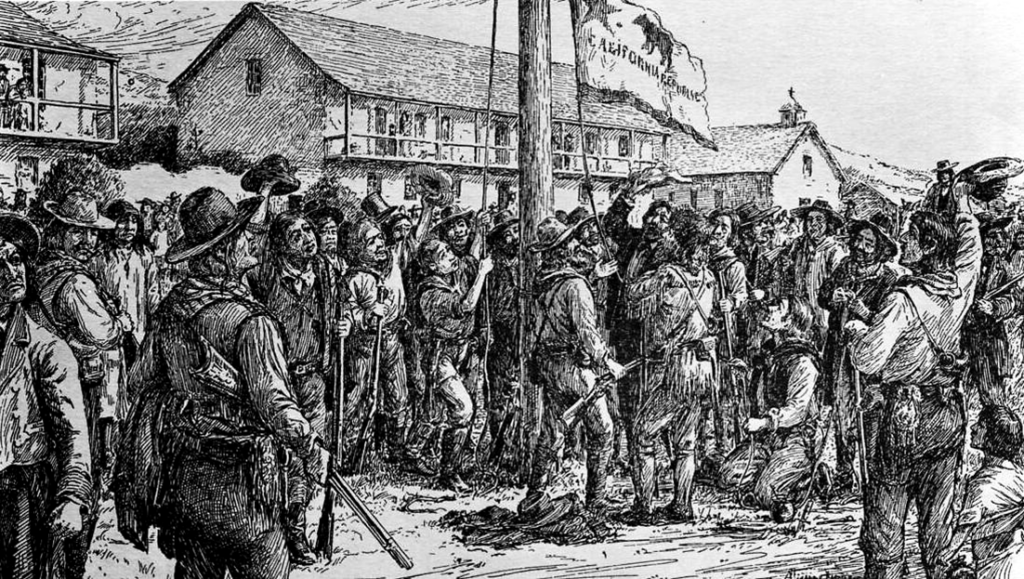

Back in Sonoma the rebels issued a proclamation declaring the overthrow of the Mexican regime and announcing the Bear Flag Republic. William Todd, a nephew of Abraham Lincoln’s wife, Mary, designed a crude flag with a star, a grizzly bear and the inscription “California Republic.” Todd was not much of an artist and one wag noted that the bear looked more like a pig. Art critics aside, they raised the flag over Sonoma on June 14.

Ide sent two of his men, Tom Cowie and George Fowler, to the Russian River to find Moses Carson, Kit’s half-brother, in hopes of acquiring arms and gunpowder from him. When the two men failed to return a search party was sent out. The Americans skirmished with a Mexican patrol and captured a soldier who confessed that the men had been captured, tortured and then killed. Godey was among those who, along with Moses Carson, discovered their bodies. They had been disemboweled with throats cut and their genitals cut off. Cowie was a great favorite of Fremont’s men, and they were enraged by his fate. The Bear Flaggers—or Osos, as the Californios called them—soon after skirmished with a detachment of Castro’s lancers and rescued William Todd and another rebel from them.

On June 25 Fremont, Carson and Gillespie with Sagundai and the Delawares, led the way as the little army rode into Sonoma. Fremont decided to journey south to the Golden Gate to see what Castro’s forces were up to. He soon moved south to San Rafael, sending out scouting parties to probe toward Sausalito. Carson, with Sam Neal and Granville Swift, intercepted three Californios at Point San Pablo. The men, one of whom was the father of the alcalde of Sonoma, were bearing dispatches from Castro.

Carson rode back to report the prisoners to Fremont. “I want no prisoners, Mr. Carson,” the captain replied. Carson returned to his men and had the three Californios summarily executed.

Fremont Takes Command

The Bear Flaggers held a grand July 4 fandango in Sonoma where they organized a 250-man California Battalion and appointed Fremont as its commander. Gillespie was to be his adjutant. Affairs were moving rapidly, and Fremont had given up any pretense of neutrality. He was now leading a rebellion. Of course, he was still ignorant of any declaration of war and so wrote a letter of resignation from the Army just in case it was needed for diplomatic cover.

Two days later Navy Capt. William Mervine hoisted the American flag over the Monterey customs house while offshore three American warships under Commodore John D. Sloat fired a 21-gun salute. As 225 sailors and Marines occupied the town, Sloat issued a proclamation annexing Alta California to the United States and assuring the local inhabitants of just and fair treatment. Soon after the Bear Flaggers lowered their flag and raised the stars and stripes. Castro wisely withdrew his small force south to Los Angeles.

On July 19, 1846, Fremont led his grizzled band into Monterey. They rode in two by two, Fremont, Carson and the Delawares in the van, each man armed to the teeth with their long rifles cradled in their arms. Offshore the British 80-gun Collingwood ominously anchored. The British, who would take no action, were as awe-struck over Fremont’s tough band as were the American sailors and Marines. Lt. Frederick Walpole, R.N., left an account:

“During our stay in Monterey Captain Fremont and his party arrived. They naturally excited curiosity. Here were true trappers, the class that produced the heroes of Fenimore Cooper’s best works… Fremont rode ahead, a spare active-looking man. He was dressed in a blouse and leggings and wore a felt hat. After him came five Deleware [sic] Indians, who were his bodyguard… The rest, blacker than the Indians, rode two by two, the rifle held by one hand across the pommel of the saddle… He has one or two with him who enjoy a high reputation in the prairies. Kit Carson is as well-known there as the duke is in Europe.”

Fremont and Gillespie promptly boarded Sloat’s flagship to meet with the commodore. Sloat was shocked to learn that Fremont had acted on his own authority without any news of a declaration of war. Sloat had received word of the battles at Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma before departing the Mexican coast, but he had no official word that war had been declared. Old and ill, Sloat now vacillated about cooperating with Fremont’s land operations. Fortunately, Commodore Robert Stockton had just arrived with full authority to supersede Sloat, which he did. As bold as Sloat was timid, he was also politically ambitious, self-assured, well-connected in Washington, and determined not to allow this opportunity for glory to pass. He and Fremont immediately formed a mutual admiration society.

Stockton now mustered the Bear Flaggers into the service of the United States as the California Battalion with Fremont in command as major, Gillespie as captain and second in command, Ezekiel Merritt as quartermaster, Dick Owens as captain and Alex Godey as lieutenant. Stockton and Fremont now turned their full attention to the south, where Castro and Governor Pico were raising an army.

Fremont, with 120 men, was to sail to San Diego on Capt. Mervine’s Cyane while Stockton, on the Congress, would land his force at San Pedro just south of Los Angeles. The voyage on the Cyane was not rough but most of the men still became terribly seasick. Carson was particularly downtrodden and swore never to leave land again. The three-day voyage ended with an uncontested landing in San Diego. In fact, the local officials welcomed Fremont warmly and aided him in acquiring horses and cattle for his march north to Los Angeles. As the Americans moved north, General Castro and Governor Pico moved on. On August 13, 1846, Stockton occupied Los Angeles without a struggle. The leading citizens, Andrés Pico, the governor’s brother, and Jose Maria Flores surrendered and promised never to bear arms against the United States. Stockton issued a proclamation announcing that California was now part of the United States, the people were now U.S. citizens, and that a civil government with free elections would soon follow. California was conquered, or so it seemed.

Stockton, anxious to sail for the southern coast of Mexico to assist American forces there, appointed Fremont as governor and Gillespie as secretary of California. Fremont selected Carson to carry dispatches with the news of the conquest of California back to Washington. “It was a service of high trust and honor, but of great danger also,” Fremont later recalled. “Going off at the head of his own party with carte blanche for expenses and the prospect of novel pleasure and honor at the end was a culminating point in Carson’s life.”

Kearny’s Folly

Carson was to report directly to Senator Benton who would then take him to meet Secretary of the Navy Bancroft and President Polk. Carson’s party consisted of his trusted friend Lucien Maxwell, 14 men as well as a train of pack mules. He felt he could reach Washington in 60 days. Near the Santa Rita del Cobre mines in New Mexico they encountered Mangas Coloradas and a large encampment of Apaches preparing a revenge raid into Mexico. Mangas was pleased to hear from Carson that the Americans were now also fighting the hated Mexicans. Mangas informed Carson that a White man he called the “Horse Chief of the Long Knives” had taken New Mexico from the Mexicans.

Mounted on fresh mules provided by Mangas, Carson pushed on toward the Rio Grande. On October 6, 1846, he encountered Gen. Stephen Watts Kearny with 300 dragoons. The “Horse Chief” had marched across the Santa Fe Trail with his First Dragoons, the First Regiment of Missouri Mounted Volunteers under Col. Alexander Doniphan, and the Mormon Battalion of 500 men whose services had been essentially purchased from Brigham Young at Council Bluffs, Iowa—dubbed the Army of the West—and bloodlessly conquered New Mexico. Now he was on his way to conquer California.

Carson informed the general that Fremont and Stockton had already taken California. Kearny sent 200 of his dragoons back to Santa Fe and ordered Carson to lead him back to California. Carson protested but to no avail. His dispatches were carried east by his old friend Tom Fitzpatrick, who was Kearny’s guide. Carson was so angry he considered slipping away in the night, but Maxwell talked him out of it.

Carson unhappily guided Kearny’s depleted army westward from the Rio Grande, through the mountains and along the Gila River to its juncture with the Colorado without incident. From Mexican horse traders they learned of a revolt in Los Angeles against the Americans. Kearny decided to march to San Diego rather than Los Angeles. Carson led them across the brutal desert, tough on men and horses, to Warner’s Ranch (a commercial center comparable to Sutter’s Fort in the north) in the first week of December. From there Kearny sent a message off to San Diego with the news of his arrival.

The Californios were indeed in full revolt against their new American overlords. Flores and Andrés Pico had broken their parole, declared California free of all foreign control, and had driven Gillespie out of Los Angeles and forced he and his small 50-man force to seek sanctuary on an American ship at San Pedro. News of the rebellion quickly reached Stockton and Fremont in the north. Stockton promptly sailed in the Congress down the coast to

San Diego while Fremont, with his California Battalion marched south from Monterey to Los Angeles. Flores had only a few hundred untrained men with which to resist the Americans. Andrés Pico, with another 100 well-mounted Californios was sent to guard San Diego.

Stockton sent Archibald Gillespie with 39 men and a little four-pound cannon to reinforce Kearny. The two met on December 5, and Gillespie informed Kearny that Pico with 100 lancers was camped just nine miles away at an old Indian village called San Pasqual. Despite the jaded nature of both his men and horses Kearny decided to attack.

Kearny sent a dragoon patrol forward to scout the enemy position, but they were spotted. With the element of surprise lost, he foolishly prepared to attack the Californios at dawn. Cpt. Abraham Johnston and Kit Carson led the advance with about a dozen dragoons. Almost immediately Johnston was shot out of the saddle, while Carson’s horse stumbled and threw him. He regained his bearings after nearly being trampled by the charging dragoons, found the weapon of a fallen dragoon, and tried to join the fight, but he was soon left behind. The Americans on their jaded horses were strung out so that their charge proved ineffective. The Californios, superb horsemen all, counterattacked. Gillespie went down with three lance wounds. He somehow crawled to a nearby cannon and fired it into the advancing lancers before fainting. Pico’s men then aban-doned the field leaving 18 Americans dead and 15 more, including Kearny, wounded. Amazingly, Kearny would later claim San Pasqual as a victory since he held the field.

The survivors retreated to a little hill to bury their dead. Godey and two others were sent to Stockton to beg for help but were taken prisoner. An effort to advance toward nearby water was forced back and the men dug in. They were now in a desperate situation with little water and only mule meat to subsist on.

Kearny called for volunteers to slip through the Californio lines and reach San Diego. Carson, Navy Lt. Edward Beale and Beale’s Indian striker came forward. Under cover of darkness the three men slipped down the hill. They removed their boots to muffle the sound as they passed so close to the Californio lines that they could smell the smoke of their cigaritos. Pico had learned from Godey that Carson was with the soldiers and had warned his guards to be wary.

“Carson is there,” he declared, “se escapara el lobo.”

The messengers managed to get through the lines and into the open valley below. Carson never doubted their escape. “I have been in worse places before,” he told Beale, “and Providence has always saved me.”

They separated in hopes one would get through. They had lost their boots in the hills and now had to cross 35 miles of hills, cactus and rock in their bare feet. The Indian (whose name is lost) reached San Diego first, Beale following and Carson arriving last. Stockton had already sent his Marines, mounted on mules, to rescue Kearny.

What was left of the Army of the West reached San Diego on December 12. Several sharp skirmishes would follow before Pico was defeated near San Gabriel River some 10 miles from Los Angeles on January 8, 1847, the anniversary of Andrew Jackson’s great victory at New Orleans back in 1815. On January 10, Los Angeles was reoccupied, and Gillespie was given the honor of raising the stars and stripes.

Fremont’s Final Years

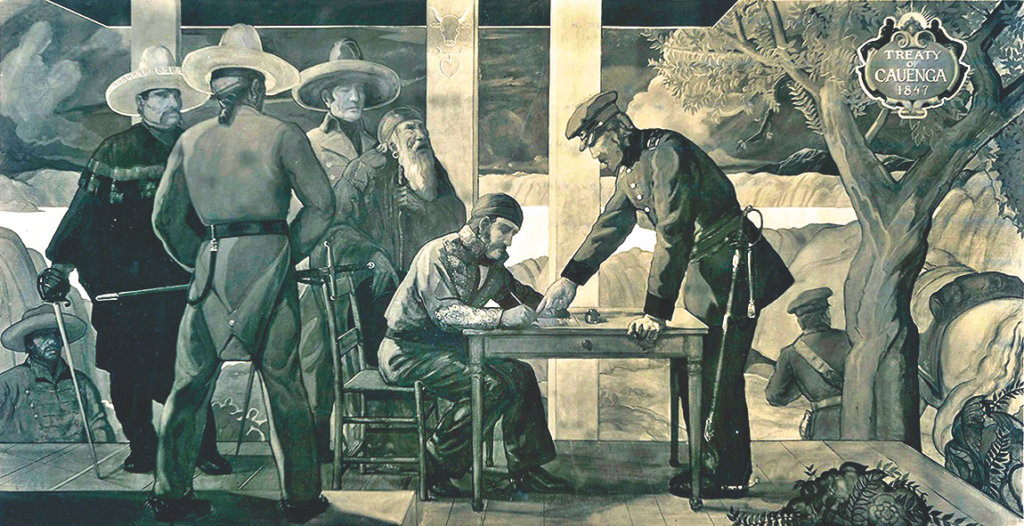

Fremont had missed all the action, but he arrived with his California Battalion just in time to accept the surrender of Andrés Pico. He encountered the Californio army just to the north of Los Angeles and offered generous terms that led to the Treaty of Cahuenga on January 13. The war for California was truly over.

Kearny, already humiliated by his “victory” at San Pasqual, and nursing wounds both physical and mental, was angered by Fremont’s action in accepting the surrender without consulting his superior officers. He was then further enraged when Fremont, officially appointed governor by Stockton, declared that he would take orders only from the commodore. Kearny seethed, bided his time, and when the Army returned to Fort Leavenworth in June 1847, he had Fremont arrested on charges of mutiny and disobedience of orders. A highly controversial and embarrassing court martial followed in which Fremont was convicted and ordered to be dismissed from the service. President Polk remanded his sentence, but the proud and wounded Fremont resigned from the Army. It was a sorry end to a glorious and significant military career.

Fremont would return to California, establish a large ranch, make a fortune in the gold rush, be elected in 1850 as the first senator from the new state, and become the first candidate for president of the fledgling Republican Party in 1856. He later served as a major general in the Civil War, but failed on the battlefield and feuded with President Lincoln after which his career spiraled downward. Before he died, impoverished and all but forgotten on July 13, 1890, Fremont wrote bitterly of his fall from glory: “I close the page because my path of life led out from among the grand and lovely features of nature, and its pure and wholesome air, into the poisoned atmosphere and jarring circumstances of conflict among men, made subtle and malignant by clashing interests.”

Carson loyally stood by his friend through all his travails. He later said of Fremont: “I am incapable to do him justice in writing…. And I say, without fear of contradiction, that none but him could have surmounted and succeeded through as many difficult services, as his was.”

Carson as Dispatch Rider

On February 25, 1847, Carson departed Los Angeles with letters and dispatches for President Polk and Senator Benton. He was charged by Fremont with telling his side of the conquest of California back in Washington (Kearny and Stockton both sent separate reports by sea). He was a guest at the Benton home and met with President Polk, but quickly soured on the politicians in Washington. “They are princes here in their big houses,” he remarked to Jessie Fremont, “but on the plains we are the princes. What would their lives be without us there?”

Carson was soon on his way back to California with dispatches for the new governor, Colonel Richard B. Mason. Fremont had already departed for the east and his court martial. He delivered his mail to Mason’s adjutant, a young red-headed lieutenant who was thrilled but a bit disappointed upon meeting the frontiersman. “His fame was then at its height, from the publication of Fremont’s books, and I was very anxious to see a man who had achieved such feats of daring among the wild animals of the Rocky Mountains, and still wilder Indians of the Plains,” recalled William Tecumseh Sherman. “I cannot express my surprise at beholding a small, stoop-shouldered man, with reddish hair, freckled face, soft blue eyes, and nothing to indicate extraordinary courage or daring.”

Carson’s courage and daring would be on constant display in the years to come: as dispatch rider, Army scout, Indian fighter and trusted Indian agent. In the Civil War he battled invading Confederates in New Mexico and ended that conflict as a brigadier general. By the time of his death on May 25, 1868, at Fort Lyon, Colorado, he was a living legend.

In crowded lives of high adventure and grand achievement Carson and Fremont must surely have reckoned the conquest of California—and the eventual addition of the 31st star to the flag—as one of their greatest accomplishments. Jessie Benton Fremont left them a poignant epitaph when she wrote that upon the lonely ashes of their campfires rose the great cities of the American West.

Armed For Conquest

Thomas Martin, a 27-year-old Tennessean, joined Fremont’s third expedition at St. Louis in June 1845. He eventually settled in Santa Barbara, California, where he served as city marshal and deputy sheriff. In 1878 he dictated a memoir to Edward F. Murray, who was gathering material for Hubert Howe Bancroft. The Martin manuscript resides in the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkley. In one of the interesting points of his story, Martin describes how each man in the expedition was outfitted:

“In June of 1845, we went by steamer from St. Louis to Westport Landing on the Missouri River, and thence marched to our rendezvous, about 8 miles from Independence. Here we formed our camp and proceeded to get everything in readiness for our final start. Most of our party were Americans, the others being French Canadian and Delaware Indians. Each man’s equipment was furnished by the Govt. to be deducted afterward from his wages, and consisted of 1 whole-stock Hawkens rifle, two pistols, a butcherknife, saddle, bridle, pistol holsters and 2 pr. Blankets. For his individual use each man was given a horse or mule for riding and one or two pack animals to care for… Three weeks after our arrival at the rendezvous, everything being in readiness we started on the expedition.”