Follow the path of law and order from Fort Smith to Guthrie via Tahlequah and Muskogee.

Russ Jester, Courtesy United States Marshals Museum, Fort Smith, Arkansas

The law came to Indian Terri-tory, which would become Oklahoma, but it came—at first —through Fort Smith, Arkansas.

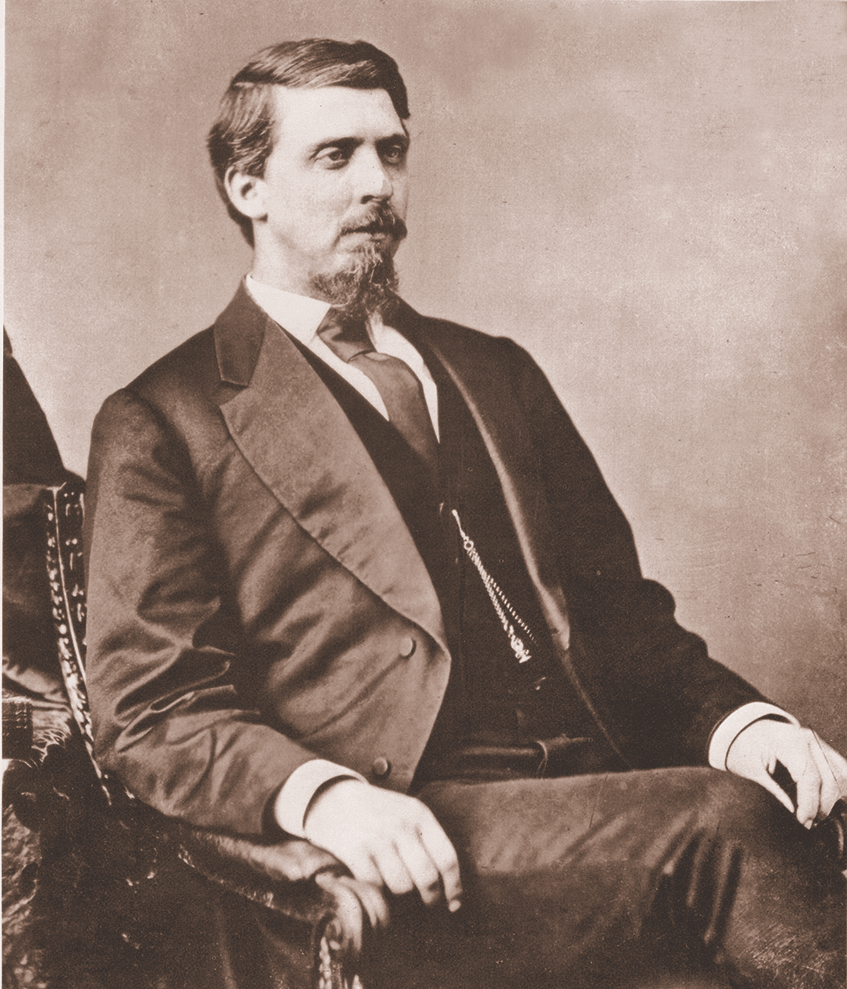

On May 10, 1875, Isaac Parker sat on the bench for his first appearance as judge for the Western District of Arkansas. That included 18 Arkansas counties and all of Indian Territory, 74,000 square miles that a Kansas newspaper in 1874 called “the ever ready criminal’s paradise.”

Which a small group of deputy U.S. marshals had to police.

As the saying went: “There is no Sunday west of St. Louis—no God west of Fort Smith.”

At least that’s what many think. After all, Charles Portis’s True Grit and other novels, films and TV series couldn’t be wrong. But there was law in the Indian Territory long before Parker’s reign.

“The Five Civilized Tribes—Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek and Seminole—were recognized by the U.S. government as self-governing nations with their own allotted lands, and each tribe had its laws, courts, and police force,” Art T. Burton writes in Black, Red, and Deadly: Black and Indian Gunfighters of the Indian Territory, 1870-1907. “The Native Americans’ police were called ‘Lighthorse’ because they were a mounted police force.”

But then—and today—Indian jurisdiction was limited.

“Indian courts had no jurisdiction over White invaders,” Burton notes. “Moreover, they lost jurisdiction over every Indian who committed any crime against, or in company with, a White.”

A Lawman Named Sixkiller

In the Cherokee capital of Tahlequah, a national prison was completed in 1875. The first high sheriff of the two-story sandstone institution, the only penitentiary in Indian Territory until 1901, was Sam Sixkiller.

“The statistics show that there is much less crime in the Indian Territory than is generally supposed,” the Boston Evening Transcript reported in 1881. “There are only 28 persons in the Cherokee penitentiary, and a large number of the reported cases of violence come from the presences, lawlessly, of White men in the Territory.”

Sixkiller left the job in 1880, became the Union Agency’s captain of Indian police and was hired as a federal deputy for Parker’s court. Sixkiller—whose “duties more nearly corresponded to…a Wyatt Earp or a Wild Bill Hickok,” historian William T. Hagan observed, was murdered in 1886 in Muskogee.

Deputy Marshals

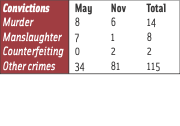

The February 21, 1876, issue of the St. Louis Globe-Democrat reported these numbers from the 1875 terms of Fort Smith’s U.S. district court:

Eighty-six men were hanged at the Fort Smith gallows from 1873-96 and 79 of them per Parker’s sentence, though he sentenced 160 to death. Parker tried 13,490 cases and sent many to the Detroit House of Corrections, reportedly because it had a good trade school.

But the Globe-Democrat also pointed out the price federal deputies sometimes paid for trying to bring criminals to justice: 23 deputies, guards and posse members killed, and 27 wounded “while in charge of prisoners, or in endeavoring to arrest men for whom they had writs.”

And that was just by early 1876.

Frank Dalton, brother of those Daltons who turned to bank and train robbery, pinned on a deputy marshal’s badge in Fort Smith in 1884. On November 27, 1887, Dalton and Deputy J.R. Cole tried to arrest Dave Smith in the Cherokee Nation. Dalton was wounded, then brutally murdered, leading the Fayetteville (Arkansas) Democrat to state “it is becoming too hot for deputy marshals in the Indian territory.”

More than 120 deputies were killed in what is now Oklahoma between 1872 and 1971.

Law Comes to Guthrie

Parker’s jurisdiction got smaller with the Courts Act of 1883, which reduced Parker’s territorial authority to the Five Civilized tribes and split the rest of the territory into courts in Kansas and Texas. Congress would continue to tweak with the federal courts until Oklahoma statehood came in 1907.

In 1889, the town of Guthrie sprang up when the Unassigned Lands in Indian Territory were opened to non-Indian settlers. With the creation of the Territory of Oklahoma a year later, 32-year-old E.D. Nix was appointed U.S. marshal, the youngest U.S. marshal in history. Guthrie became Oklahoma’s territorial capital in 1890 and state capital from 1907 to 1910.

With outlaws like Bill Doolin and the Daltons running around in the 1890s, Nix hired deputies including Heck Thomas, Bill Tilghman and Chris Madsen. That trio would become known as The Three Guardsmen for their exploits, although historian Nancy B. Samuelson has written that those deputies—and their boss—were involved in “questionable and illegal activities” themselves.

Yes, in 1896 Tilghman arrested Bill Doolin in Eureka Springs, Arkansas, and returned him to Guthrie. After Doolin escaped from the Guthrie jail, Thomas led the posse that killed the outlaw. And Madsen, who died in 1944 at age 92, had a long career in law enforcement.

But Samuelson argues that Madsen “hoodwinked” a number of historians with his “tall tales” and spent most of his career behind a desk. That while Thomas’s “record as a deputy U.S. marshal under the Fort Smith court

is probably without equal,” he was probably a bigamist. That Tilghman “did as much to break the law during his life as he

did to enforce it.” And that Nix “turned out to be a very good press agent for himself.”

Photo of Guthrie by Johnny D. Boggs/

Historic Photo of Guthrie Courtesy True West Archives

Bass Reeves

But one lawman’s record remains untarnished.

Born into slavery in Arkansas, Bass Reeves was commissioned a federal deputy in 1875 and worked out of Fort Smith and then Paris, Texas. In 1898, after a year in Wetumka, Indian Territory, Reeves was transferred to Muskogee. Over a career of more than three decades, Reeves reportedly arrested more than 3,000 people and killed 14 outlaws. He even arrested his own son, who was convicted of murdering his wife. When the federal marshal suggested that another deputy make the arrest, Reeves responded: “Give me the writ.”

After his death in 1910, the Muskogee Daily Phoenix eulogized the lawman: “In the history of the early days of Eastern Oklahoma the name of Bass Reeves has a place in the front rank among those who cleaned out the old Indian Territory of outlaws and desperadoes.”

A Wide Spot in the Road

WOODY GUTHRIE CENTER

There ain’t no fancy doctors Here to bind the cowboy’s hurt; We jest warsh it at th’ waterhole Then we dry it on his shirt.

Woody Guthrie’s “Cowboy’s Philosophy” showcases how the songwriter remembered his Oklahoma and Western roots.

Ten years ago, the Woody Guthrie Center opened in Tulsa, about an hour northeast of his birthplace in Okemah. It’s dedicated to preserving Guthrie’s legacy and vision. In addition to exhibits, the Tulsa museum houses a growing archives and special collections with more than 10,000 items.

The Guthrie Center is located next door to the Bob Dylan Center, which houses exhibits and archives of another iconic American songwriter who didn’t ignore the West (the soundtrack for the 1973 movie Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid and the song “John Wesley Harding,” even though Dylan misspelled the gunman’s last name). woodyguthriecenter.org

Good Eats & Sleeps

Good Grub: Bricktown Brewery, Fort Smith, AR; The Branch, Tahlequah, OK; Back in Time Diner, Muskogee, OK; Simone’s Café, Guthrie, OK

Good Lodging: Beland Manor Inn Bed and Breakfast, Fort Smith, AR; The Lodge at Sequoyah State Park, Hulbert, OK; Stoney Creek Hotel, Broken Arrow, OK; Pollard Bed and Breakfast, Guthrie, OK