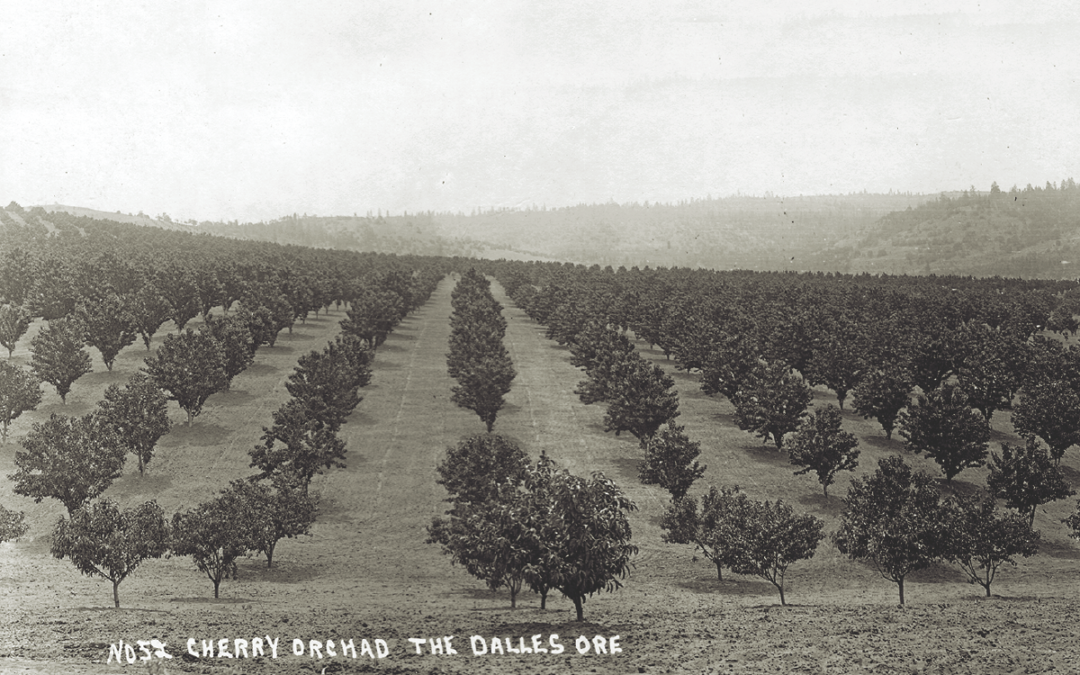

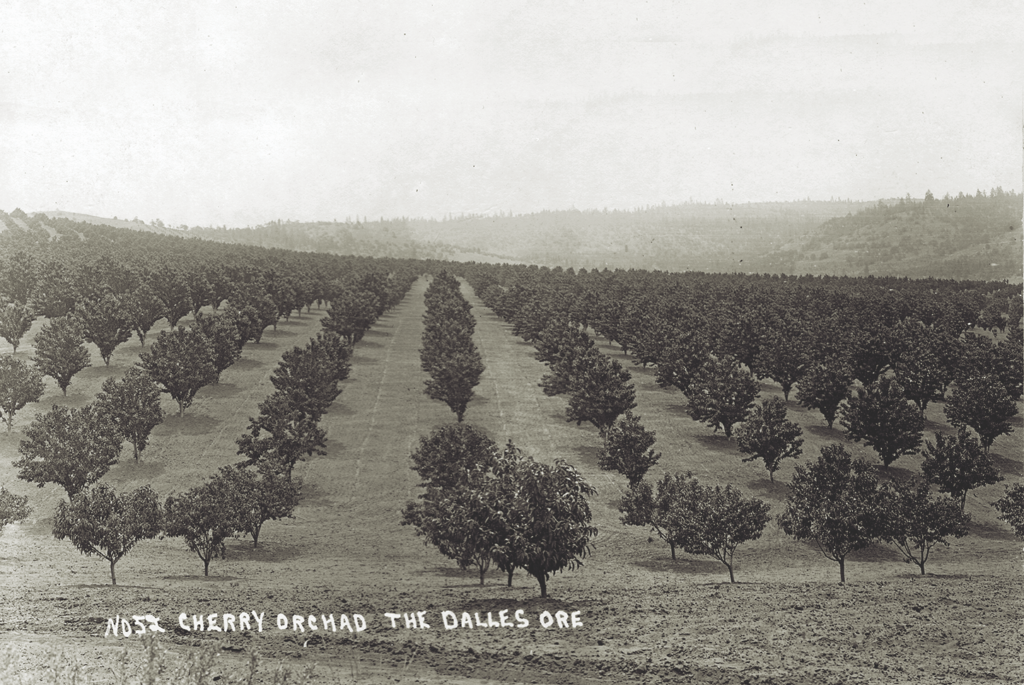

The Beaver State, one of the great cherry-producing areas of the world, grows many varieties—from Bings to Royal Annes.

Oregon has been known for its cherries since the 1840s after pioneers settled the region, but the native wild cherries were small, tart and bitter. Knowing the territory was ideal for growing fruit trees, settlers began planting apple, pear, peach and cherry trees. Some early cherry varieties included Red Marilla, Early May, Red Carnation, May Duke, Vanskike and Cluster. Traditional cherries were often yellow and pale red in color until the Bing cherry arrived, which made the dark cherry market explode.

In 1847, Henderson Lewelling arrived in Oregon from Iowa and planted his first orchard of cherries. His brother Seth joined him soon thereafter, and in 1875 Seth planted a new cultivar of sweet cherry trees in his Milwaukie, Oregon, orchard. According to his stepdaughter Mrs. Herman Ledding, “…the Bing cherry was named in honor of a Chinese workman… Bing was close to six feet tall, if not more… The manner in which the cherry was named for him happened thus: He and my stepfather were working the trees, every other row each. When they discovered this tree with its wonderful new cherry, someone said, ‘Seth, you ought to name this for yourself.’ ‘I’ve already got one in my name,’ Seth said. ‘No, I’ll name this for Bing. It’s a big cherry and Bing’s big, and any way it’s in his row, so that shall be its name.’”

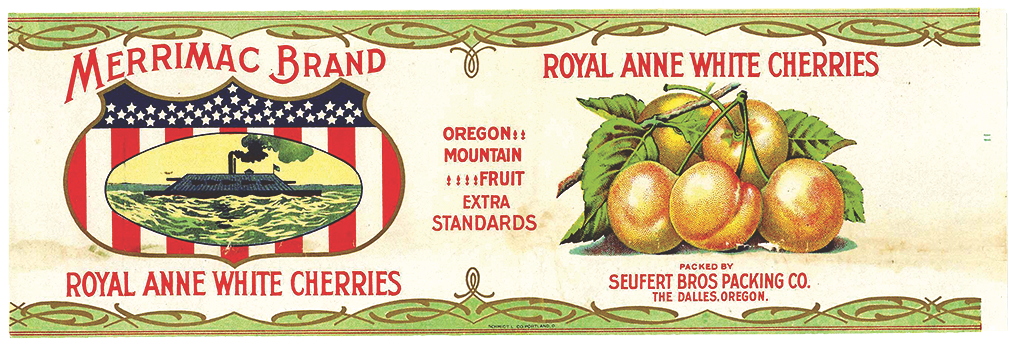

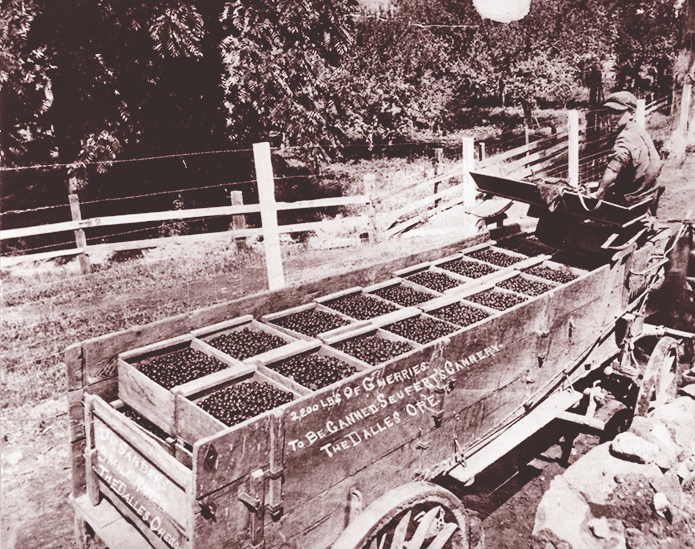

In the mid- to late-1800s, the Royal Anne was an all-purpose cherry and was used in three main ways. One was for fresh eating, another was for canning, but the third and primary use was in making maraschino cherries. The Medford Mail wrote, “So keen is the competition for the Royal Ann [sic] that the maraschino buyers often overbid the canneries a full cent a pound or more.”

One of the leading firms making the maraschino cherries was E.G. Lyons & Raas in San Francisco. In 1907 they purchased and packed 650 barrels of Oregon Royal Anne cherries at seven cents a pound to make maraschinos. Mr. Arthur Raas also put up several barrels of cherry juice to make cordials and soda fountain items. The Corvallis Gazette wrote, “Oregon grown Maraschino cherries have gained a world-wide reputation for size and flavor and command the highest prices in the market.”

By the 1900s the popular cherry varieties planted were Royal Anne, Bing, Lambert and Black Republicans. In 1902 The Oregon Daily Journal offered a large spread on ways to eat cherries. Recipes included cherry Charlotte, water-ice, tarts, in syrup, a cherry cup and fruit salad with cherries.

In addition to cooking with them, pioneers made brandy and cordials, women wore cherry blossoms in their hair and decorated their homes with them, and many towns had parades and fairs—all to honor the cherry.

Maraschino Cherries

½ cup sugar

½ cup water

1 ½ cups cherries, pitted

1 cup Maraschino liqueur

Place the sugar and water in a medium saucepan and turn to low heat. Bring the mixture to a simmer, cover, and allow to cook for 5 minutes. Turn the heat down to low and add the cherries. Cook the cherries at a simmer for about 3 minutes, until they’re slightly softened. Remove from the heat and stir in the liqueur. Allow the mixture to cool completely and refrigerate until ready to use.

Recipe adapted from the Lincoln County Ledger, October 1, 1909.