She was born in a house her father built.

A little house, naturally. Her father would build many more little houses as he carried his family from one place to another.

The girl, however, would grow up to do big things. I mean, Laura Ingalls Wilder practically made people forget that “Pa” was once Little Joe Cartwright. And more than 41 million readers can’t be wrong. That’s just books in print. How many parents have passed down hardcovers and paperbacks to their own children…grandchildren…?

Laura Elizabeth Ingalls Wilder arrived in the big woods of Wisconsin on February 6, 1867, and so on the 150th anniversary of her birth, we’re following one of the West’s and the world’s most beloved children’s writers.

It starts here in Wisconsin, in “a little gray house of logs” about 7.5 miles north of the Mississippi River town of Pepin.

“There were no houses,” Laura wrote in Little House in the Big Woods (1932). “There were no roads. There were no people.”

The big woods have been cleared for farmland, and the roads now see people, mostly “Lauraheads” making pilgrimages. The cabin’s a replica. In the 1970s, the Laura Ingalls Wilder Memorial Society Inc. was organized, bought three acres of the Ingalls site and erected a reconstructed cabin and marker.

Charles Ingalls, a jack-of-all-trades better known as “Pa,” had married Caroline Quiner in 1860 in Jefferson County, Wisconsin, and moved to Pepin County two years later.

“Pa was no businessman,” Wilder told her daughter, Rose Wilder Lane. “He was a hunter and trapper, a musician and poet.”

Pa also had a “wandering foot” that often “got to itching.”

On to Kansas

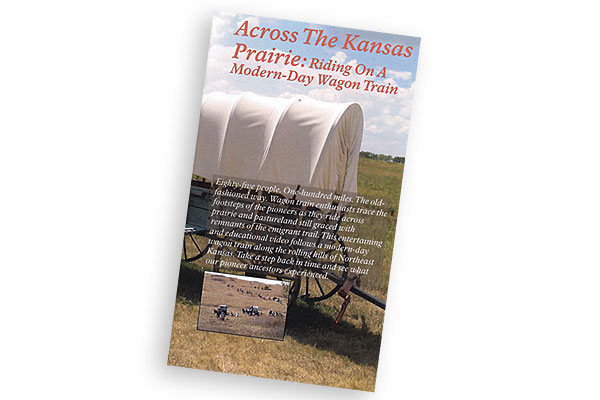

In the spring of 1868, Pa sold his 80 acres and set out by covered wagon with his family—Ma, Laura and her older sister, Mary, and younger sister, Carrie (sister Grace would arrive in 1877)—for Kansas. Maybe he had grown sick of gathering honey, making sugar from maple sap, planting, butchering, fishing, shooting, trapping….

Pa was “an unsettled person,” says author Candace Simar, a Spur Award-winner and finalist for Western juvenile fiction. He most certainly kept unsettling and uprooting his family.

By 1869, Pa had built another little house. This one was on the prairie. Specifically, it was the Osage Diminished Indian Reserve in Kansas. Pa was squatting illegally.

“Pa built a house of logs from the trees in the nearby creek bottom and when we moved into it, there was only a hole in the wall where the window was to be and a quilt hung over the doorway to keep the weather out,” Laura wrote in her autobiography, Pioneer Girl.

Jean Kurtis Schodorf’s grandfather acquired the historic property outside of Independence in 1923. He didn’t know its significance. In fact, no one did until 1969. In 1976, the Kurtis family, some “old-timers” and Jaycees decided to build a replica cabin exactly like the one Laura describes in Little House on the Prairie (1935).

“It took us three months, and 90 volunteers with chainsaws and pickup trucks,” Schodorf recalls.

The site today also includes the 1885 Wayside post office and the 1871 Sunnyside schoolhouse, and, of course, the hand-dug well (covered for obvious reasons). Schodorf plans on adding an Osage exhibit this year.

Back to the Old Northwest

In Little House on the Prairie and Pioneer Girl, Laura writes that the Army evicted the family, forcing their return to Wisconsin. Yet the land would soon be open for settlement, so Pa might have had another reason for uprooting the family. The farmer who bought Pa’s Wisconsin property back in ’68 hadn’t been able to pay the mortgage. So the Ingalls clan returned to the big woods in May 1871.

They stayed there until February 1874—check out the Laura Ingalls Wilder Museum in Pepin. After the family came down with scarlet fever—to which Laura attributed sister Mary’s blindness in By the Shores of Silver Lake (1939)—wanderlust again got the better of Pa. In May 1874, they had a little home on Plum Creek in Minnesota.

“It was a funny little house that we moved into,” Laura wrote in Pioneer Girl, “not much more room than in the wagon, for it had only one room. It was dug in the side of the creek bank near the top.”

The homestead lies roughly 1.5 miles north of Walnut Grove. Like the Kurtis family in Kansas, the Gordon family of Minnesota knew nothing about its history when Harold and Della Gordon bought the property in 1947, discovering its literary value later that year. The family has continued to make the site accessible for Lauraheads—even planting native grasses, which Laura described so beautifully, over 25 acres.

Only a depression remains of the dugout. Pa’s buildings have long since vanished. The mosquitoes, which Laura wrote about in By the Shores of Silver Lake, thrive.

Insects, of course, weren’t the only troubles on Plum Creek. Locusts plagued the West in the early 1870s. “They ate every green thing,” Laura wrote in Pioneer Girl, “the garden, the grass, the leaves on the trees.”

Crop failures sent Pa retreating south. In 1876-77, the Ingalls family lived in Burr Oak, Iowa, where Pa helped a friend manage the Masters Hotel, now the Laura Ingalls Wilder Park and Museum. One hotel door was riddled with bullet holes, a saloon stood next door, and “we were a little afraid of the men who were always hanging around” the saloon, Laura recalled.

Laura skipped over her Burr Oak years in her “Little House” books. Perhaps the loss of her nine-month-old brother, Freddie, proved too painful to write about. (She also omitted her Spring Valley, Minnesota, and Westville, Florida, sojourns of 1890-92, but those came as an adult.) The family returned to Minnesota in 1877 and Laura let W.P. Kinsella (Shoeless Joe, The Iowa Baseball Confederacy) bring literary glory to Iowa.

Walnut Grove—“only a tiny town”—became even more famous when the TV series became a hit. (Aside: For years, I always thought Walnut Grove was in Kansas.) Much of the memorabilia displayed at the town’s Laura Ingalls Wilder Museum is from the TV series, but the museum also houses a quilt owned by Laura and Rose.

The Dakota Territory

In 1879, Pa landed a railroad job and left for Dakota Territory. Ma and the girls followed him in September by train—well, for seven miles at least, to Tracy. “We are sorry to lose them,” a correspondent wrote in the Currie Pioneer, “but what is our [loss] is their gain.”

And ours, too.

Because Laura’s years in and around De Smet, South Dakota (1879-1890, 1892-94), gave us the bulk of her “Little House” novels: By the Shores of Silver Lake, The Long Winter (1940), Little Town on the Prairie (1941), These Happy Golden Years (1943) and The First Four Years (1971). It was here that she met, courted and married Almanzo Wilder, whose New York boyhood was chronicled in Laura’s Farmer Boy (1933).

And, as my guide told me on my visit to the Ingalls Homestead: “We have the coolest stuff.”

You might get some argument elsewhere, but the Ingalls Homestead is impressive. The hours vary, and it’s closed from November 1 until late April. Read The Long Winter and you’ll know why. Or, during the summer, twist hay into sticks for fuel—another indication of how hard winters can be up here.

At age 16, Laura began teaching school to help pay for Mary’s tuition at The Iowa College for the Blind. On August 25, 1885, she married Almanzo. Daughter Rose, an equally talented writer (and at the least a coach and editor for her mom), arrived in 1886, the same year Pa finally filed papers on his 157.25-acre homestead. He stopped moving, and died in 1902 in De Smet, where he and many other family members are buried.

Laura, however, had one more move.

The Final Homestead

In 1894, she and Almanzo headed to Mansfield, Missouri—chronicled in her diary On the Way Home (1962)—where they bought what she dubbed Rocky Ridge Farm, now the Laura Ingalls Wilder Historic Home & Museum, where many treasures, such as Pa’s fiddle, are displayed.

At age 65, Laura began writing and “Little House” became a literary success.

“It was a long story,” she said, “filled with sunshine and shadow.”

Laura died in 1957, eight years after Almanzo’s death, but her writing resonates with and teaches children—and grownups—today, tomorrow, forever.

“Laura’s voice continues to ring out throughout the years,” Simar says, “speaking of the realities of pioneer life and making readers around the world understand and remember.”

Years ago, Johnny D. Boggs read all of the “Little House” books to his son, before Jack discovered jazz and Impractical Jokers.