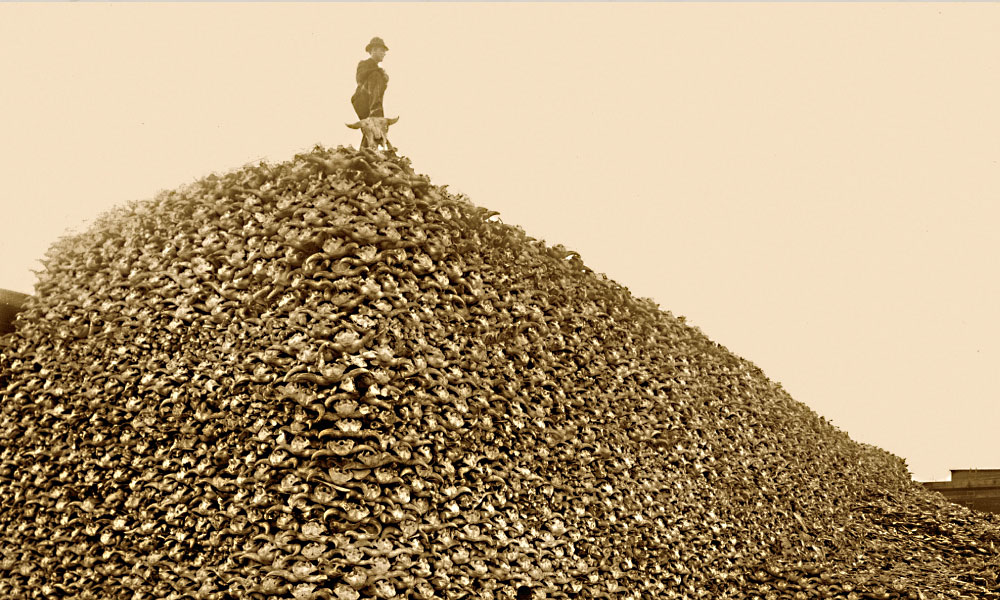

– Courtesy NPS.gov –

A bull bison looked at me from the diorama at the Boot Hill Museum in Dodge City, Kansas, when I began to hear a rumble. As the sound in the room grew louder, a herd (pun intended) of elementary school students came rushing into the small room where I stood. The kids tumbled onto the floor as the rumble became louder and louder.

“It’s a massage,” the kids yelled as they lay on the floor that had begun to shake along with the rumble. On a series of four small monitors above the bison mount, Buck Taylor (you might remember him as Newly on Gunsmoke) and Dodge City spokesman Brett Harris shared stories of the bison that once roamed by the hundreds of thousands across the plains. When images from the film Dances with Wolves showing a bison hunt by American Indian hunters swept across the screens, the rumble of pounding hooves became louder and louder, the floor shook harder, and the school students yelled in delight.

These youngsters may or may not have learned anything about the historic Great Plains bison herds, but they almost certainly went home talking about the experience they had at the museum. But Boot Hill Museum has more to represent the era of the buffalo hunters, including a display of buffalo hunter guns.

Dodge City

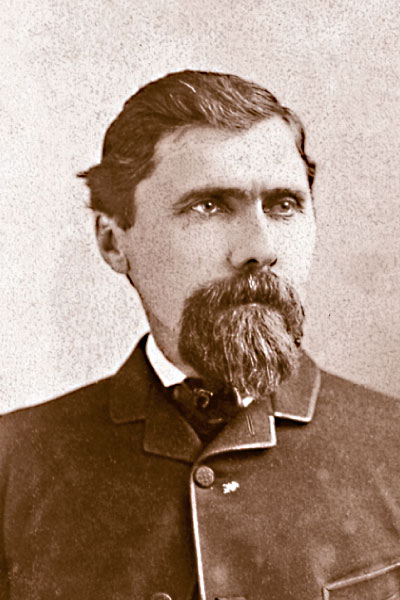

Dodge City was a center of the buffalo trade in the 1870s when Josiah Wright Mooar arrived. Born in Pownal, Vermont, Wright left home at age 19 and after spending some time attending school in Michigan, and then working in Illinois, he went west to Hays City, Kansas, where he found work cutting firewood for use at Fort Hays.

He saved enough money to buy a buffalo hunting outfit, and with three wagons and four hired hunter/skinners set out in search of the Great Plains herd along the Smoky Hill River. Wright worked his way south to Fort Dodge, and caught a break in 1871-’72 when Charles Rath, a freighter and hunter, received an order for 500 buffalo hides for an English tannery. Rath enlisted the aid of Wright Mooar in providing the requisite number of hides.

When the hides to fill the English order were shipped to New York City some left over were hauled through town in an open wagon. A Pennsylvania tanner saw them, and at the urging of Wright’s older brother, John Wesley Mooar, who worked in New York City, the tanner bought the excess hides. After processing, he liked the leather so much that he placed a new order for 2,000 more hides. This kind of enterprise required serious commitment, so John Wesley Mooar quit his job and joined Wright to handle the business end of buffalo hunting, arriving in Dodge City in November 1872.

The buffalo-hunting trail of Wright and John Wesley Mooar took them south into the Texas Panhandle, where thousands of bison were eating upland grass. During the fall of 1873 hunting season the Mooar hunting team would “take a wagon, a roll of bedding, and a little grub and, with a four-mule team, would drive out on the divide that separates the North Palo Duro from the Canadian [River],” Wright wrote. “There we would interrupt the buffalo herds that were crossing.…We stayed on the divide until we loaded our wagon with hides and meat. We could haul 10,000 pounds with four mules when the ground was frozen. We could load, come back to camp, unload, and go back again.”

John Mooar further explained the work in a letter written to their mother on Oct. 31, 1873. “Have no fear about Wright and me. We are on the frontier.…Times look promising here now.…We are bold, tough, hearty, and rugged.…We have some hardships to endure and also some good ones. We can’t set a nice table, but our food is of the best in the way of meat that the world affords. The things we sit down to eat in camp would make a meal for a king.”

Historical Marker: Buffalo Trails

The Texas Panhandle

My route takes me south from Dodge City and Fort Dodge across the Oklahoma Panhandle, and into the Texas Panhandle, where the Mooar brothers hunted in 1873 and 1874. These and other buffalo hunters constructed a trading post they called Adobe Walls, about a mile from the earlier fort of the same name. As they hunted through the country, the Mooars had brushes with Indians, but they loaded their wagons with hides and set off for Dodge City without incident, barely missing involvement at the Second Battle at Adobe Walls, and the seemingly miraculous long-distance shot by Billy Dixon that killed a Comanche and became a pivotal moment in the conflict.

This fight resulted in the subsequent attack on Comanches in Palo Duro Canyon in 1874 by Col. Ranald S. Mackenzie, who not only routed the tribesmen, but also killed about a thousand of their horses, ultimately forcing the Comanches out of West Texas and onto a reservation in Oklahoma Territory.

The Mooars and other buffalo hunters now had a much safer area in which to ply their weapons and they killed thousands upon thousands of head of bison, ultimately working their way east to the country along the Brazos River and Fort Griffin, which had been established in 1867.

My journey takes me to Canyon, Texas, near Palo Duro Canyon and home of the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum with its outstanding murals by Harold Bugbee depicting some of the buffalo hunter legacy. From Canyon, I headed south to Lubbock and the History Museum at Texas Tech, where History Curator Henry Crawford, who often appears as a buffalo hunter re-enactor in living history programs, takes me into the archival collections for a view of personal items that belonged to John Wesley and Wright Mooar, including John’s gun, photographs and even a teething ring!

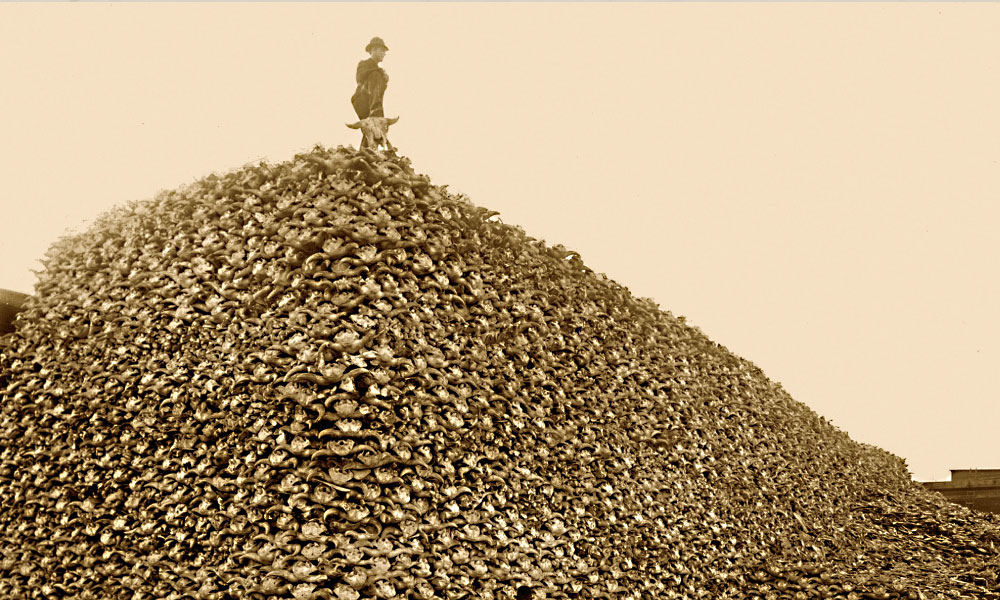

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

The Southern Plains of West Texas

Heading east from Lubbock, I drive through the country where the big buffalo herds once roamed. I’m on my way to Fort Griffin, which has just opened a new visitors’ center that tells the story of the buffalo hunters, the Comanche and Kiowa Indians, the frontier military and the early settlers in the area around Albany, Texas.

Each October the fort comes to life when modern-day re-enactors set up camp and share stories of the people who were at Fort Griffin in the 19th century. Located on a high plateau, Fort Griffin provides a stunning view of a landscape in many ways little changed from the days when Wright and John Mooar hunted buffalo in the area.

Fort Griffin State Park and Historic Site represents primarily the military era, with a nod or two to the buffalo hunters. The civilian side of life in the region during the 19th century is down the hill at the town of Fort Griffin, known as The Flat. There you’ll see the original jail in a community that was pretty raucous in its heyday. If you ask at the visitors’ center, they can give directions to other historic sites in the area, including a Comanche treaty ground.

By 1875 the Mooar brothers were based out of Fort Griffin, chasing—killing —the big bison herds in the area. Wright said, “When you’d shoot a buffalo in the lights, he’d throw blood out of his nose. Then he’d step backward a step or two, flop over and die. If you shot him through the heart, he’d run about four hund-red yards before he’d fall, and he’d take the herd with him.”

Wright had learned to pick the leader of the herd and shoot that animal first. “As soon as I killed him, the others would stop running. They would mill around, bellow, paw the ground, and smell the blood.”

For each hunting stand, Wright tried to move within a hundred yards before firing the first shot. He wrote, “The best bunch you’d get a stand on was one of two or three hund-red.…I never used a rest stick. I shot off my knee or sat down and rested both elbows on my knees.Some-times I lay flat on my stomach, with elbows spraddled.”

While the shooting was underway the skinners who had the wagons remained at

a distance, but Wright added, “When I got through [shooting] and gave them the signal, they’d go to the first buffalo and skin him and throw the hide in the wagon.”

Mooar would eventually hunt as far south as Fort Concho, and had already hunted in the area west to Palo Duro Canyon. In 1878 Wright hauled a load of buffalo meat to Prescott, Arizona, and later he took a delivery to Colorado City, Texas. But the bison herds were soon decimated, destroying a way of life for the native people of the region as well as the hunters who had shot themselves out of a business.

The brothers married and ultimately settled in West Texas. John sold carriages and owned land in Colorado City and Wright ranched near Snyder.

– Courtesy The Lyda Hill Texas Collection of Photographs in Carol M. Highsmith’s America Project, Library of Congress –

In one of her other lives, road warrior Candy Moulton creates exhibits and films for museums and visitors’ centers. She wrote and produced the new interpretive film for Fort Griffin State Historic Site.