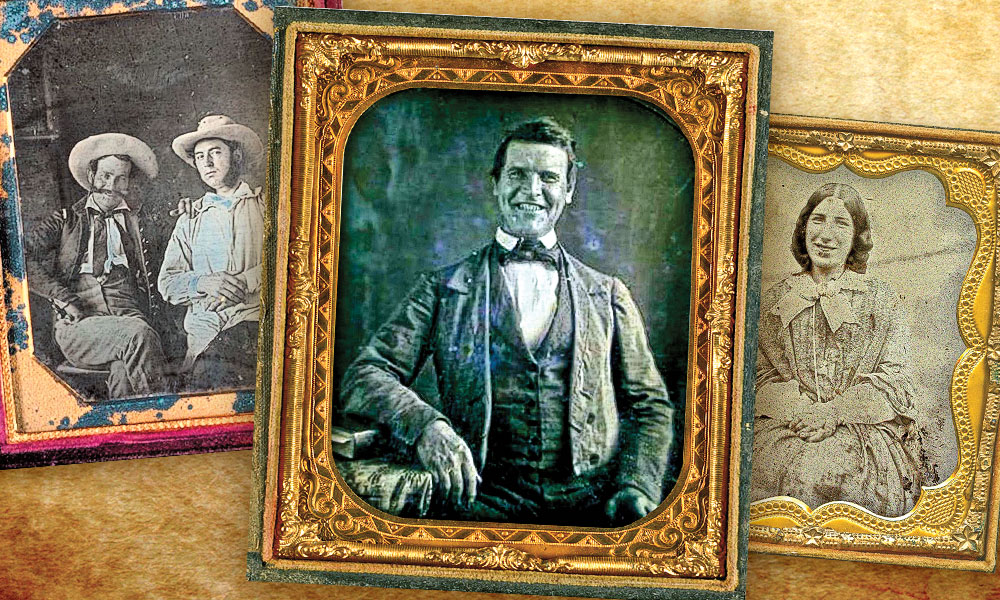

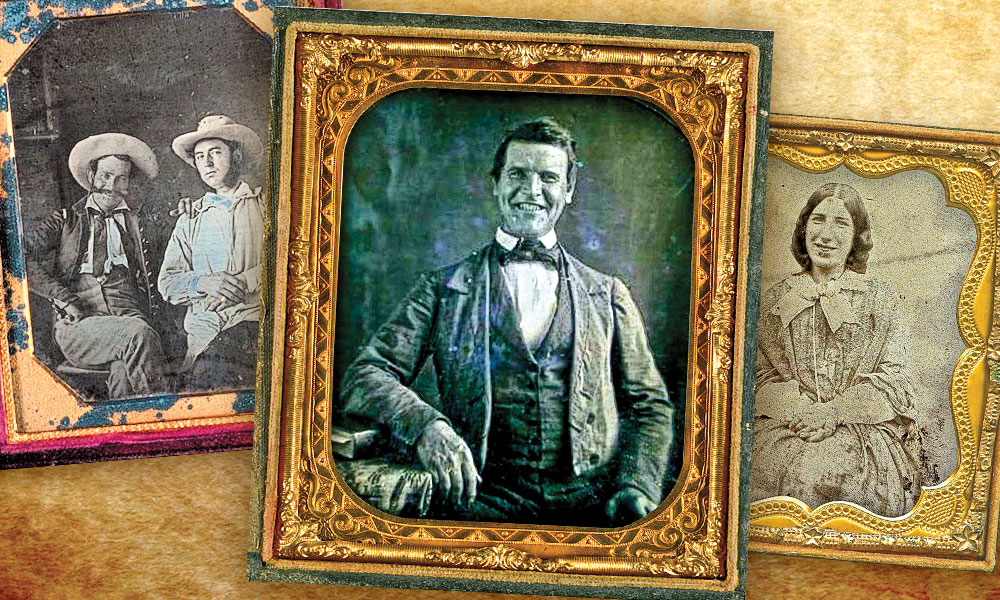

Most people who study photos from the 1800s,

whether these are family photos or historical images of the American West, have wondered why the people all look so stern and even sad. Although several

theories have surfaced over the years, none of

them are entirely correct.

One theory, often expressed by older family members, is that people back then didn’t have anything to be happy about. Yes, times were different and folks lived lives that were, in many ways, harder than our lives now, but they were also finding fulfillment with community and family at parties, socials and church and community functions. Contemporary newspapers are filled with notices of balls, ice cream socials, picnics and parties for every possible occasion. Pioneers knew how to have fun and often did.

Bad teeth and poor dental care is another rationale. We actually have more teeth problems in modern times because of the amount of sugar in our diet. Those among us who can afford it can get our dental issues corrected. When our ancestors broke a tooth, the practice was to pull it, instead of fix it. Yet even famous people who were known to have good teeth didn’t smile when sitting for a photograph.

The length of time people had to sit perfectly still for photographs, due to slow exposure times, is another explanation for the lack of smiles in historical pictures. A brief history of photography is called for to explain why this theory doesn’t measure up.

In 1826 or 1827, Nicéphore Niépce took the first permanent real-world photo. The exposure time was several days. Louis Daguerre, who invented the daguerreotype around 1837, cut down the time to roughly 15 minutes. That’s quite an advance within a decade.

The first “selfie” was taken by Robert Cornelius in 1839—with an exposure time of about a minute! He dashed out of the frame and closed the lens cover before the camera could register the movement.

After Daguerre took the first known photo of a human in 1838, American photographers took an estimated 30 million daguerreotypes. These images were cherished because, being exposed directly in the camera on a polished copper plate meant that the photo could not be reproduced as copies to be distributed to friends and family.

By 1842, advances in lenses and chemistry shortened exposure time to between 10 and 60 seconds. In 1851, when Frederick Scott Archer told the world about collodion, a process using glass plates, he narrowed the time to a few seconds. Still a long time to hold a smile. Try it.

One of the best-known American photographers, Mathew Brady, along with his team of photographers, traveled the battlegrounds of the Civil War to take thousands of photographs using the wet collodion process. Many Brady photographs were of horses, which did not hold their feet and tails still for a photographer to capture them on film; the horses show up perfectly still in Brady’s photographs.

By 1871, photographers began using dry plates, which cut down the exposure time even more. Six years later, Eadweard Muybridge took the first set of the famous series of photographs of a galloping horse to settle the question as to whether or not all four hooves leave the ground (they do). William Jennings, in 1882, became the first to capture lightning in a photograph.

If you could capture a horse in mid-air and lightning striking the sky, you could capture a smile crossing someone’s face.

The most recent theory on why people in 19th-century photographs appeared so serious was discussed by Nicholas Jeeves in an article he wrote for The Public Domain Review in October 2013. He introduced the theory that smiling in a photograph just wasn’t culturally acceptable. The Smithsonian, Eastman Kodak archivists and many others have filled the Internet with articles and videos on this subject, with many of them linking back to the Jeeves article.

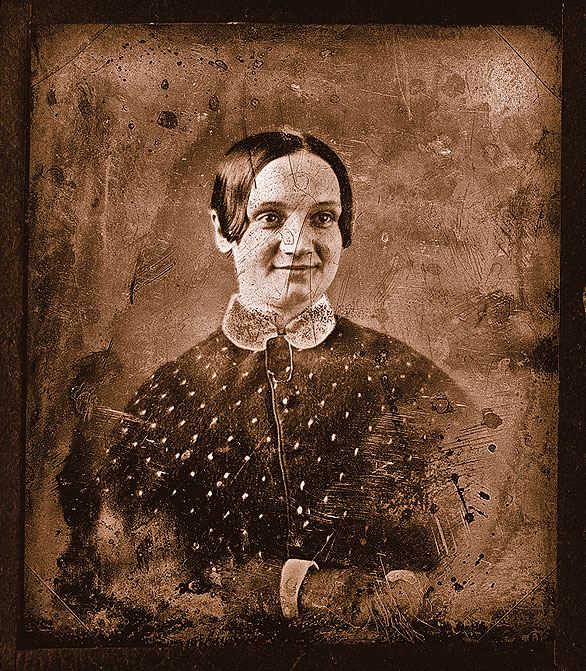

The consensus is that only fools, drunks, children and innocents smiled in painted portraits and photographs. Decorum was still as big a part of society as it was 135 years earlier, as stated by St. Jean-Baptiste de La Salle in the 1703 publication, The Rules of Christian Decorum and Civility: “There are some people who raise their upper lip so high… that their teeth are almost entirely visible. This is entirely contrary to decorum, which forbids you to allow your teeth to be uncovered, for nature gave us lips to conceal them.”

Even Mark Twain, despite being a famous humorist, didn’t smile in photographs.

“I think a photograph is a most important document,” he said, “and there is nothing more damning to go down to posterity than a silly, foolish smile caught and fixed forever.”

Most people had one, if any, photograph taken their entire lives, sometimes to commemorate a special event like a wedding or an anniversary. Traveling photographers appeared only occasionally in the area or set up a short-term studio. Views of families in front of homesteads were popular. They wanted to be remembered for their accomplishments on the frontier.

That said, occasional “slips” of decorum and smiles can be found in Victorian and earlier photographs. Folks share photographs of these smiling Victorians on Flickr.com, although some of the “smiles” are debatable.

The lack of smiles in early photography is no indication of the internal lives of the people who peer out from these images. The Old West ranchers, gunfighters, storekeepers and miners may have led hard lives, but most also knew how to have fun. The happy moment came, not from a smile captured on film, but in owning a photograph personal to you and your family that allowed one to share his prosperity and pride with future generations.

Rita Ackerman is the author of O.K. Corral Postscript: The Death of Ike Clanton. A professional genealogist and researcher for nearly 40 years, she has written a monthly column for The Tombstone Times for more than 10 years and has also been published in The Tombstone Epitaph and Wild West Magazine.