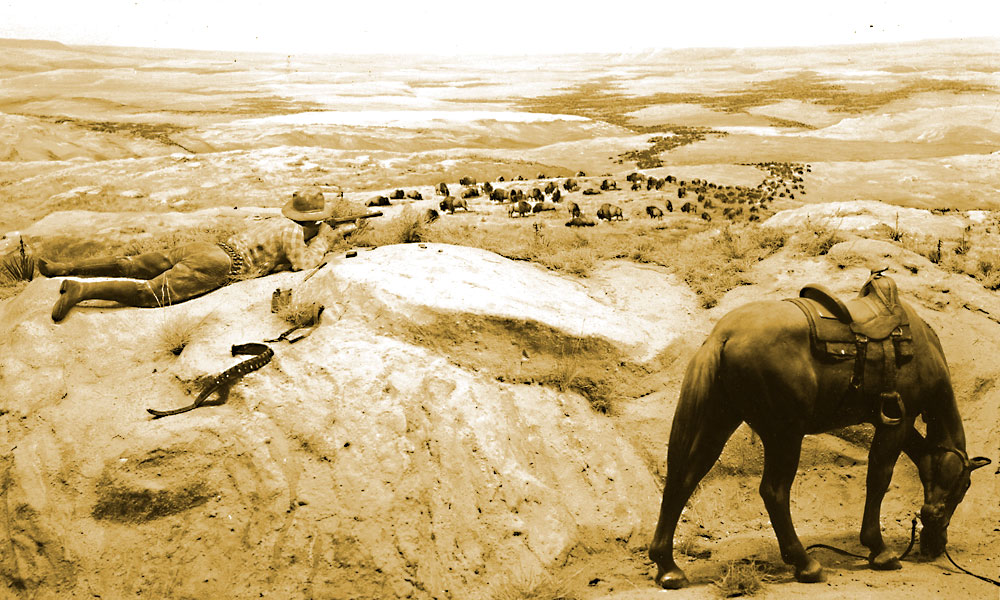

– Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration, Scotts Bluff National Monument –

Comanche Chief Black Horse stared out across the High Plains of West Texas in December 1876 in disbelief. The grasslands before him looked like the floor of a slaughterhouse. Painted over the grass and dirt were large dark streaks of blood leading away from the bloating carcasses of hundreds of bison.

Cheyennes had earlier returned to the Darlington Agency in Oklahoma with tales of whole herds of buffalo killed off to the north, resulting in rioting at the agency that had to be put down by U.S. troops. The Comanches scoffed at their stories. To them, the Cheyennes were panicking over nothing.

But as promised government beef rations had been shorted on the Fort Sill reservation, due to budget cuts, Black Horse obtained permission to take his followers out onto the Staked Plains for a buffalo hunt. Some 170 followed him to West Texas, including white captive Herman Lehmann, who had been with the Comanche for less than a year after escaping from the Apaches.

Witnessing firsthand a mass slaughter that matched the descriptions of the plagued herds in Kansas, Black Horse could tell multiple parties of whites had been responsible, just by the different methods used for the slaughter. Some left the head on the carcass, while skinning the animal; others had cut the head off first before skinning. Now and then, the Comanches found a rod or stake driven through the neck of a bison, whose hide had been cut around the horns, belly and legs. The skin was then detached by using horses to quickly pull the hide right off the carcass. A few of the majestic beasts had their tongues ripped out. What remained of the meat was left to rot.

For the moment, plenty of buffalo still roamed the southern edge of the Staked Plains, but the wanton slaughter angered the Comanche band so much that they refused to return to the reservation. They became determined to reap revenge on the white hunters.

The Killing of a Species

Both U.S. Army policy in killing off the buffalo herds, so as to deny warring tribes a food source, and the national depression of 1873 resulted in a relentless extermination of the majestic creatures.

On Christmas Day in 1874, two skinners and 20-year-old Joe McCombs embarked on the first hide expedition into the south end of the Staked Plains from Fort Griffin. Within two months, they skinned 700 bison. Moving to a new location, McCombs took 1,300 more hides. All the while, McCombs reported he and his skinners saw no one else.

Word circulated that the southern end of the Staked Plains were empty, save for thousands of buffalo for the taking. About a dozen outfits plunged into the Staked Plains from Fort Griffin, including the Mooar brothers. J. Wright Mooar claimed he killed 96 bison in one stand, bested only by Frank Collinson, with 121 bison killed in a stand just north of today’s Childress. Robert Cypret Patrack wrote about being part of a crew of 16—two hunters, one cook and 10 skinners, with two men hauling hides and one loading ammunition.

Feeling crowded at Fort Griffin, German-born Charles Rath moved 50 miles west to set up his outfitter post along the Brazos River in 1875, which he called Rath City. Some 80 hunters followed him to the killing grounds, including future lawman Pat Garrett. The Fort Worth newspaper carried daily stock quotes for hides direct from the Galveston exchange. The hide business in the southern section exceeded one million dollars in 1877.

With bison on their last legs in Kansas, the hunting grounds attracted hunters like a magnet. Among them was frontiersman Charles “Buffalo” Jones. Though Jones complained about the slaughter, the money was too good for him to turn his back on, as he had two small boys to feed.

Jones arrived in Fort Griffin, finding the easy money that had brought him to West Texas also brought in a rough criminal element. The character of men working out of Rath City was even worse.

– Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration –

Tortured to Death

Chief Black Horse was watching too. Furious, he broke his agreement on returning to the reservation and took his people into Pocket Canyon for the winter. When the weather eased up in February 1877, Black Horse and his Comanches struck.

Marshall Sewall, who had set up his stand below Caprock near the head of Salt Fork, killed 21 bison with his new Sharps Creedmoor .45 rifle. When Sewall headed to his camp, the Comanches attacked. Three skinners and another hunter hid out while Sewall screamed from the torture. They found him with two scalp locks taken. His body was stretched out naked, with gashes cut into his temples and one into his navel. The legs of his rifle’s tripod stood in the three gashes. The four men hurried to Rath City for help.

Forty men rode back to Sewall’s camp. They buried the buffalo hunter and set out to track the Comanche war party. When they caught up to Black Horse, a skirmish broke out. The posse wounded and captured Comanche Spotted Jack before they returned to Rath City.

The Comanches had also attacked Garrett’s camp, driving off his horses. They did the same to Willis Glenn.

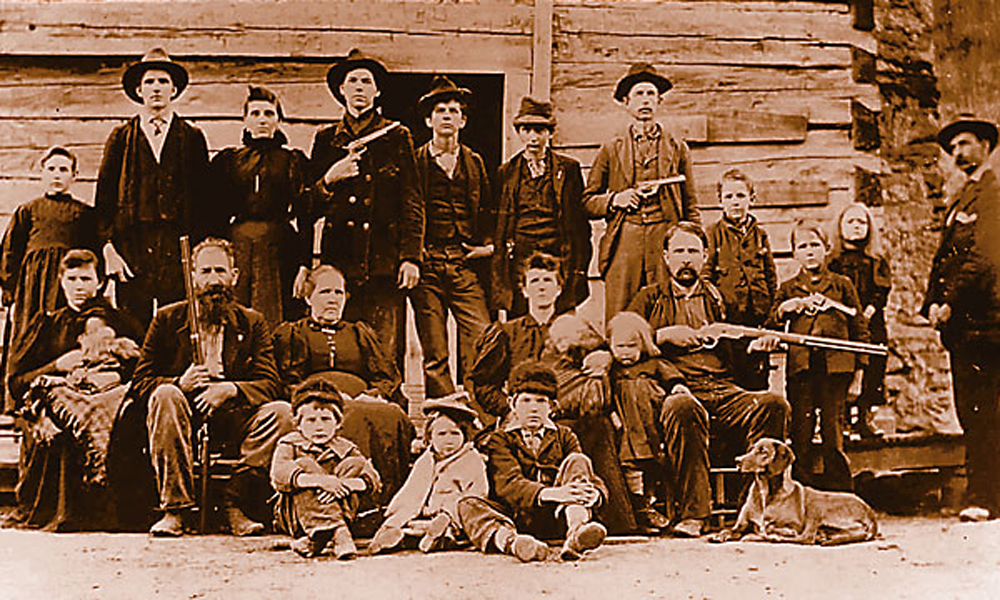

Hundreds of armed men, including Jones, Garrett and John R. Cook, gathered at Rath City from across the Staked Plains. The volunteers were quickly organized by former mountain man Smoky Hill Thompson, who Jones described as a white-haired, Kit Carson type. Thompson asked one group to hunt down the Comanches and the other to guard Rath City.

Out of those men, 125 agreed to fight. Most guarded the town, while 45 set out on the expedition. Thompson excused himself as too old to go.

Hank Campbell was elected commander of the punitive expedition, while José Tafoya, a former Comanchero from New Mexico, agreed to guide the crew. He claimed he had guided Col. Ranald Mackenzie’s troops during the Battle of Palo Duro Canyon against the Comanches on September 28, 1874.

Of the 45 men, 20 did not have mounts, so Capt. Jim White obtained two wagons—one for hauling the men, and the other to haul feed and whisky.

The captain soon discovered Tafoya was taking the troops in the wrong direction. Two days out, White began bleeding from the lungs and turned back. Jim Smith was selected as the new captain. Smith led the men to where Sewall was killed; from there, Tafoya picked up the Comanches’ trail.

Tafoya guided the volunteers west to the caprock’s escarpment near today’s town of Post. He told the hunters he believed Black Horse’s band was heading for Yellow House Canyon, near present-day Lubbock. The immensity of the treeless Staked Plains, with its lack of landmarks, already bewildered the expedition. Jones, for one, thought they were more than 100 miles north of their actual position.

Quietly making their way to the mouth of the canyon, they found a sentry and killed him. Tafoya was sent ahead where he found Black Horse’s camp.

Campbell decided to march through the night and surprise Black Horse at dawn. The men hid provisions and their wagons at the mouth of the canyon. On the night of March 17, 1877, Tafoya led his group to the north fork in the dark, instead of the south fork, the site of Black Horse’s camp. He quickly corrected his mistake, backtracking into the south canyon.

Campbell split his 43 men into three groups; two mounted groups climbed the canyon rim, on both the north and south sides. The third group, on foot, advanced along the canyon floor to head into Black Horse’s hideout. When within range for their pistols, the third party charged after dawn broke on March 18.

Battle of Yellow House Canyon

Caught off guard, the Comanches ran out in a panic. Then they noticed the small size of the attacking force.

The warriors set themselves up defensively to defeat the hunters, while their women ran up the sides of the canyon and fired on the horsemen from above. Now the buffalo hunters were taken aback by the ferocity of the Comanche defense.

Joe Jackson was shot in the groin and dragged to safety, while other hunters dropped before Comanche gunfire. The small band of buffalo hunters gave ground to the advancing Indians, who, Tafoya now reported, made up not just Comanches, but also renegade Apaches. Black Horse’s men fanned out into skirmish lines along the flanks of the canyon and lit the dried grass on fire for cover.

One Comanche mounted a white horse, shouting for a charge. From a distance of 300 yards, Jones and the others dropped the warrior.

“It’s a ruse, boys!” Jones shouted, as reported in the biography Lord of Beasts. “Watch this flank! They’re creeping down on us through the smoke.”

Cook heard Jones and organized some hunters to repel the flanking move. But the men were too heavily outnumbered to stand their ground. By mid-afternoon, Campbell ordered a retreat for Buffalo Springs.

With Black Horse’s warriors trailing behind, sensing a possible kill strike, Smith ordered his men to light a giant bonfire. This decoy allowed the small force of volunteers to escape south and then east. They set more fires to obscure their tracks.

Four days passed before the buffalo hunters returned to Rath City.

Lehmann was badly wounded, while Jackson died two months later from his groin wound. Causality figures from the engagement were all over the map. After interviewing Black Horse and others, the Army placed the Comanche dead at 35, with 22 wounded. As for the buffalo hunters, the Army gave no official tally. The numbers ranged from just four wounded to 12 killed and eight wounded.

The End of the Buffalo?

The fight emboldened Black Horse. His warriors ambushed and killed three more hunters, and destroyed several hunting camps. On May 1, fifty warriors raced through the street of Rath City, shooting, yelling and stealing as many horses as they could.

The 10th Cavalry was assigned to bring in Black Horse. After a sharp skirmish, most of the Comanche band returned to the reservation. The Battle of Yellow House Canyon turned out to be the last major Indian fight on the High Plains of Texas.

Within two years, the southern buffalo herd was decimated. McCombs spent from September 1878 to March 1879 on a hunt that yielded only 800 hides. Finding a herd of 50 was becoming a rarity.

“I do not recollect having seen a buffalo on the range after my return from my last hunt,” McCombs said. “There was no hunting after that.”

Though Jones earned the nickname “Buffalo Jones” from his Staked Plains hunts, he spent the decades afterwards trying to keep the buffalo from going extinct.

“I had killed buffalo by the thousands for their skins,” he wrote, “and had vowed someday to capture and domesticate enough to atone for my cussedness.”

The buffalo herd Jones introduced at Yellowstone National Park, when he was appointed the first game warden in 1902, began the long road that ultimately lifted the buffalo away from the brink of extinction.

– True West Archives –

Mike Coppock is a published author of Alaskan history works. He currently resides in Enid, Oklahoma, and he teaches in Tuluksak, Alaska, part of the year.