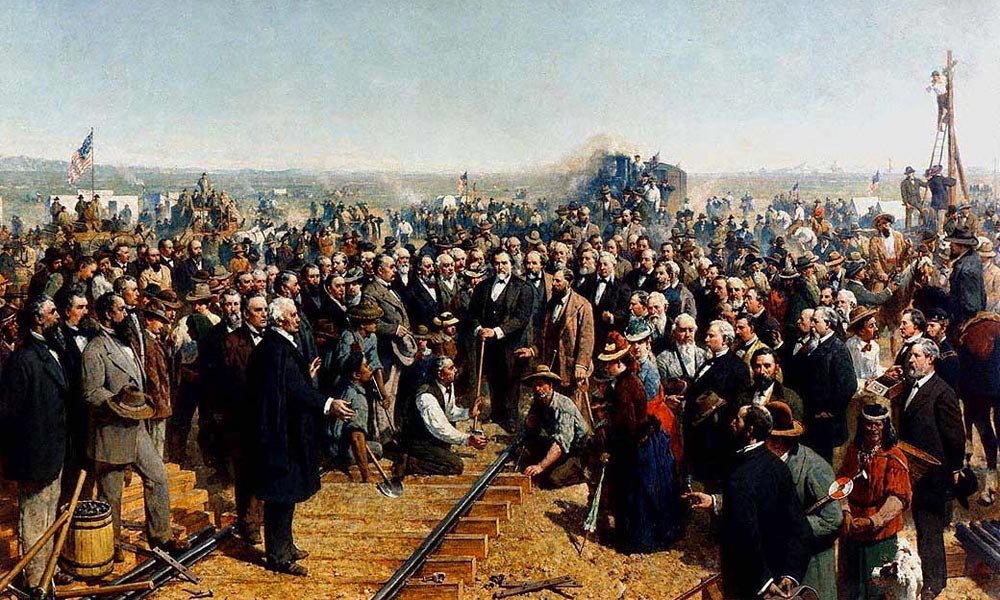

One of the most iconic paintings of the old west is “The Last Spike”, created in 1881 by Thomas Hill to commemorate the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad on May 10, 1869.

The painting has about 400 figures, 70 of which are portraits. The most commanding image is of Governor Leland Stanford, who is leaning on his hammer. Around him are his financial partners and friends who had formed the Central Pacific Associates to build the west-to-east portion of the railway that was authorized by President Abraham Lincoln in 1862 at the start of the Civil War: Collis Huntington, Mark Hopkins and Charles Crocker.

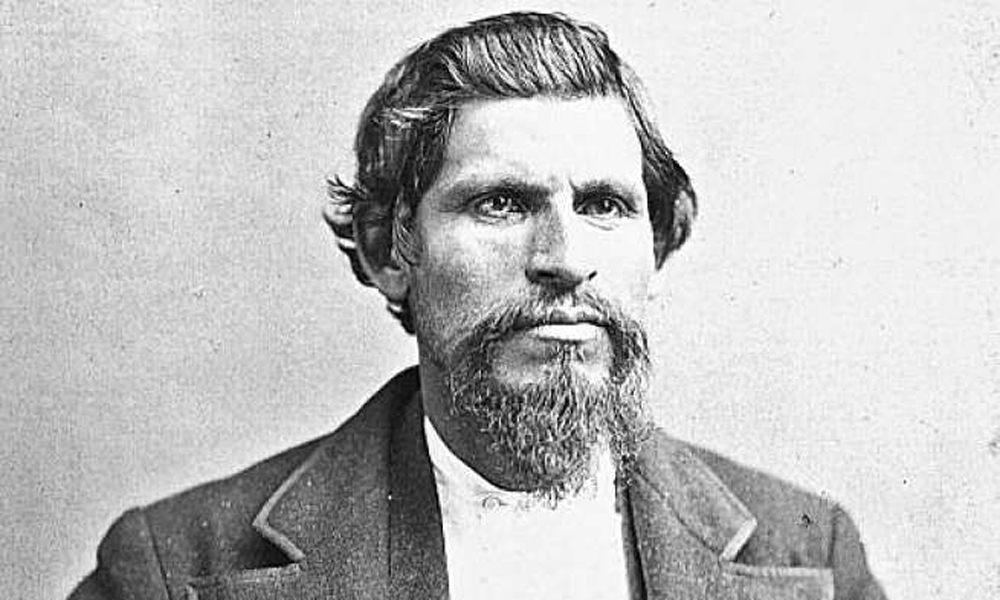

But there’s one portrait of a man who was long dead by the time the spike was set. His name isn’t famous like the others, but he was actually the “father” of this great railroad plan.

His name was Theodore Judah. He was the engineer who not only first envisioned a transcontinental railroad, but worked tirelessly to convince others it was feasible—an idea first seen as so absurd, they called him “Crazy Judah.”

Judah and his men first built the Sacramento Valley Line in 1855, the first railroad west of the Missouri River. But his big dream was always a transcontinental line. He went back to Washington, hoping to interest the new Republican Party in the plan, but got nowhere. He authored and financed a pamphlet, “A Practical Plan for building the Pacific Railroad,” and distributed it to Congress in 1856. But he found a federal government “divided” over what would become the Civil War. But he didn’t give up. He lobbied California politicians, stressing what an economic boom a railroad would have for their products and their profits In 1859, a California convention called to advance a Pacific railroad, set him east to lobby Congress. Judah actually wrote a bill to authorize the railroad and found a sponsor, but it was defeated—again, the Civil War interfered.

He returned home and devoted himself to the other big problem that needed solving–how to get a railroad over the rocky Sierra Nevada mountains? In 1860, Judah was invited to climb Donner Pass, and a Eureka! moment occurred when he realized this was the answer—Donner Pass wasn’t double-ridged like most of the Sierra, so a railroad could climb straight to the pass before following the Truckee River down out of the mountains. He set about creating a scaled Sierra route map some 90 feet long, proving the route was feasible.

In 1861, he convinced the “Big Four” to back the project–Stanford, Huntington, Hopkins and Crocker. They were named the Central Pacific Railroad Company. Although the businessmen had cash to bring to the project, Judah did not, although he was guaranteed an equal number of shares and a place on the company board.

Off he went to Washington again, now with the backing of the powerful California businessmen, to lobby Congress and the president one more time. This time, he came home with authorization and federal money. He and his partners would build the west-to-east leg, while the Union Pacific Railroad would build the east-to-west segment. They’d eventually join up at Promontory, Utah.

The Pacific Railway Act signed by President Lincoln provided that for every mile of track laid, the railroad companies received generous financial subsidies and grants of land on either side of the line. Significantly higher payments were given for the difficult miles in the Sierra Nevada. And that’s where the conflict came. History tells us that the “Big Four” decided they could be even bigger, and get far more federal money, if they simply moved the base of the Sierra Nevada farther west, meaning they’d get the higher fees for every mile of track they built.

Judah was incensed. As True West reported in a 1991 story by Laura DeVries, “Judah refused to have his noble dream tainted by graft and greed. Once more he returned East.”

This trip was to find new investors who would buy out his California partners. Unfortunately, Judah contracted yellow fever on the trip to New York and died on Nov. 2, 1863.

Six years later, to the jubilation of the nation, the two legs of the railroad met in Promontory—they were supposed to meet May 8, but the Eastern leg was held up by enraged tie-cutters who hadn’t been paid for their work. When payment was made, the train proceeded and the final spike was actually drive in on May 10, 1869.

On that day, Anna Judah spent the day alone at her husband’s grave, marking their 22nd wedding anniversary.

In 1881, when Thomas Hill finished his famous painting, there was Theodore Judah—behind the two women to the right of the painting, as seen by the viewer, is a man facing the viewer with black hair and a beard. That is Judah. It is said that Gov. Leland Stanford requested his portrait be included.

His legacy is seen in a variety of ways. Mount Judah in the Tahoe National Forest is named for him. Judah Street in San Francisco, as well as a street car line, are named in his honor. And in Sacramento and Folsom, both memorial plaques and elementary schools are named for the engineer who was largely responsible for the transcontinental railroad.