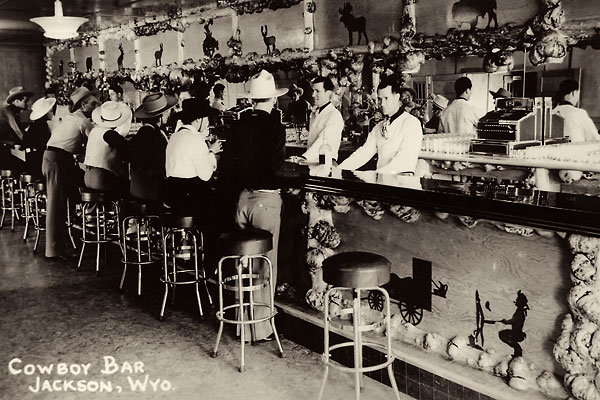

After gambling away my earnings from wrangling horses at the notorious Cowboy Bar in Jackson, Wyoming, I shipped my footlocker and saddle freight collect, and thumbed my way to Reno, Nevada.

The year was 1947, the heyday of the Nevada six-week divorce, when Reno was the place to go if you wanted to get unhitched. When I arrived in Reno, I dropped in at the Round Up Bar on West Second Street, the city’s unofficial hiring hall for cowboys. Lena Geiser, a cowboy’s widow with a warm heart and whiskey voice, ran the Round Up. Lena lent me the money to claim my saddle and footlocker, and she lined up a job for me as a backcountry trail guide at Lake Tahoe. When Lena later heard that the Flying M E needed a new dude wrangler, she set up an interview, and I got hired.

At 22, I was mature for my age. Growing up on a ranch during the Great Depression in Montana, I had been farmed out at age nine to help make ends meet. I rode the rails to see the American West. At 17, I joined the Navy and fought in the Pacific during World War II. I possessed good manners, thanks to my mother, and I was comfortable around people, both good skills for a dude wrangler.

The Flying M E

Twenty miles south of Reno, the Flying M E was an exclusive dude ranch that catered to wealthy Easterners and Hollywood film stars seeking a “quickie” divorce. The owner was Emily Pentz Wood, a petite lady my mother’s age and already a Nevada legend. “Emmy” and her husband Dore, both Eastern bluebloods, visited Nevada in the 1930s and fell in love with Washoe Valley. They purchased the 1861 Franktown Hotel and turned it into an exclusive dude ranch with the comforts their Eastern friends desired. In 1943, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt vacationed at the ranch and wrote about the “luxury dude ranch out West” in her “My Day” syndicated newspaper column. The ranch and the Woods were thrust into the national and international spotlight.

Dore eventually ran off with a wealthy guest, but Emmy continued to run the Flying M E with the help of a ranch hostess and head dude wrangler. Emmy knew her clientele and their needs. With names like du Pont and Astor, they wanted privacy from the press. When film stars such as Clark Gable, Ava Gardner and Rita Hayworth visited to get away from Hollywood, Emmy made sure her staff didn’t leak their names to the local stringers or society photographers.

“I’d Died and Gone to Heaven”

My first week at the Flying M E, I thought I’d died and gone to heaven. Most of the guests were women. Most were happy to be there. Some had their next husband waiting for them at the Riverside Hotel.

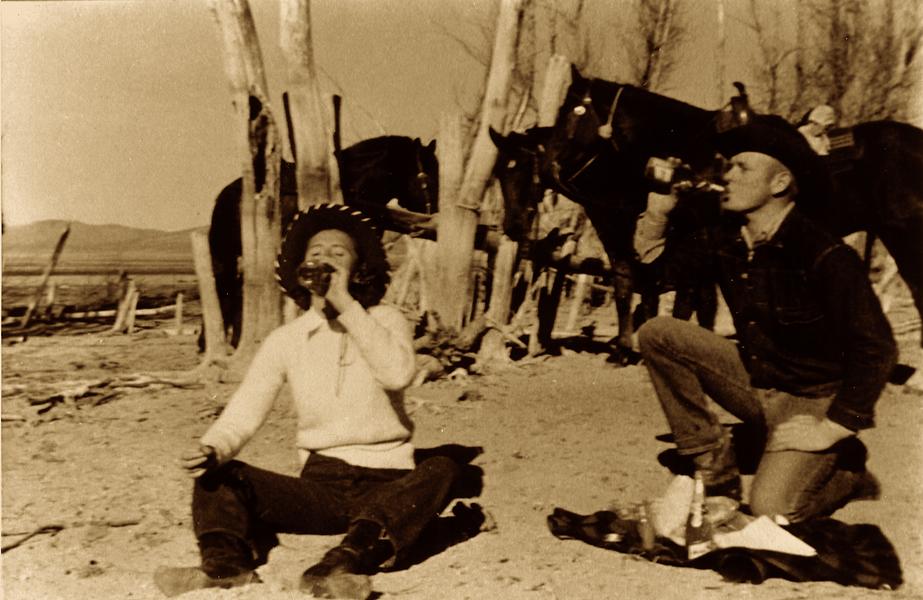

I really had two jobs. My day job was matching the guests up with horses and taking them on trail rides. I also served as the tour guide, showing guests around Virginia City, Pyramid Lake and Lake Tahoe. My night job entailed taking the guests in the ranch’s Buick wagon to the local watering holes for some gambling and entertainment. We’d avoid Reno and frequent Ella Broderick’s Old Corner Bar in Carson City (today the site of the Carson Nugget). The local men might hit on the ladies, but the ladies mostly enjoyed the attention. Occasionally a romance would develop, such as the case between Tony Green, the curator of the Nevada State Museum, and Maggie Astor. After serving her six weeks, Maggie broke off her engagement to her next-intended and ran off with Tony to La Jolla, California.

Running a dude ranch for divorce seekers was not easy. It helped to have broad shoulders and be a good listener. Emmy had two strict rules for me. “Bill,” she said, “If you go into town with six guests, you return with six guests. And you don’t fraternize with the guests.” It’s been my policy not to kiss and tell, but I had offers—a ranch in Colorado, a casa in Acapulco. Mostly I knew the women behind these offers were infatuated with me, though I was seriously smitten on a few occasions. I tried not to break Emmy’s second rule out of respect for Emmy, but what was I to do if there was a knock on my bunkhouse door?

Most of the guests were Eastern social register types. A former New York debutante came to the ranch to divorce her banker husband and met a Virginia City saloon owner. She married him and happily spent the rest of her life in Virginia and Carson Cities. Yet Emmy also had to watch out for problem guests, arranging for them to stay elsewhere if they had drank too much or were too loud. Male guests were also welcome at the ranch, to help break up the female chatter.

If you had the money and the need for privacy, a divorce ranch was where you wanted to stay. Other leading dude ranches in the area were the Pyramid Lake Ranch, Donner Trail Ranch and Washoe Pines—the latter best-known for its original resident, the cowboy artist and writer Will James, and also as the site for the film version of Clare Boothe Luce’s 1936 play The Women.

Why Reno?

Reno’s divorce boom started in the days of the Comstock when, in 1871, state courts established a six-month residency period and allowed divorces without proof of adultery. Three sensational divorce cases followed: those of Lord John Russell in 1899; Mrs. William Ellis Corey in 1906; and “America’s Sweetheart,” the Hollywood actress Mary Pickford, in 1920. Though only the Corey divorce took place in Reno (Russell and Pickford divorced in Genoa and Minden respectively), these sensational cases, followed by others, put Reno on the map as catering divorces to the wealthy and famous.

In 1931, in the teeth of the Great Depression, the Nevada legislature legalized gambling and reduced the residency period for a divorce to six weeks. The floodgates opened, and divorce seekers came running to Reno by the thousands. Reno became known as the “divorce capital of the world.” Publicity about the Reno divorce created its own jargon, such as the “Reno cure” and “getting Reno-vated.”

In the 1950s, Nevada’s divorce ranch culture began to fade away with the liberalization of divorce laws elsewhere in the nation; today, little remains from the era.

I never planned on being a dude wrangler. Looking back, however, I consider myself lucky to have been in the right place at the right time to experience this epoch of the contemporary American West. At age 84, I may be the only dude wrangler “still above ground” who experienced this colorful era.

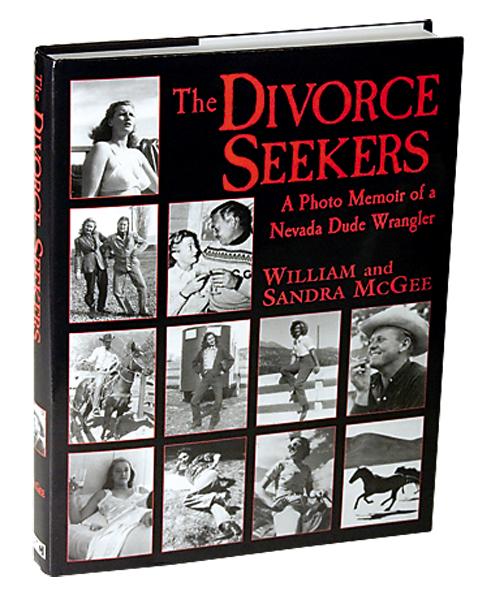

In 1950, William L. McGee left the Flying M E and made a successful transition into the film, radio and TV industry. Bill and his wife Sandra are authors of The Divorce Seekers: A Photo Memoir of a Nevada Dude Wrangler. They live in Tiburon, California, but can often be spotted at Adele’s in Carson City. Visit BMCPublications.com for video clips and book details.

Photo Gallery

Frankenstein’s Monster lived in Boulder Dam Hotel in Boulder City to establish residency for divorce in 1946. He said his wife, former librarian Dorothy Stine Pratt, was cruel to him; on April 22, he married thespian Evelyn Helmore.

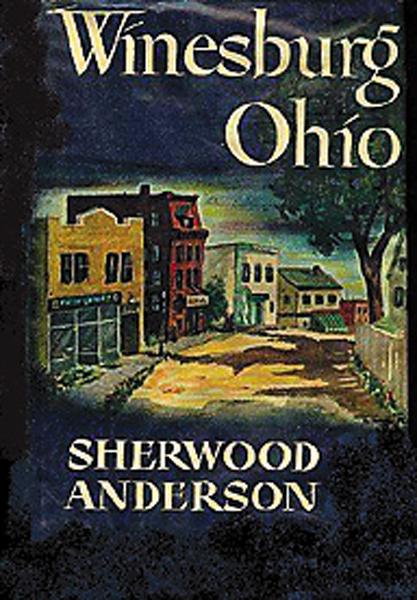

The author—famous for his collection of related short stories, Winesburg, Ohio, published in 1919—divorced sculptor Tennessee Mitchell in Reno in 1924.

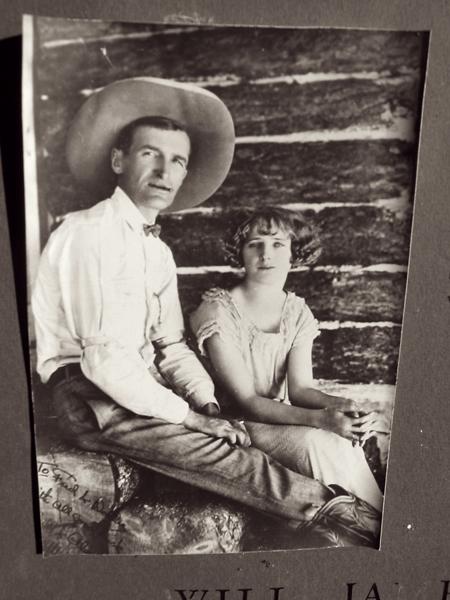

– Courtesy Collection of the Jackson Hole Historical Society & Museum, Neal Rafferty Album –

Dorothy Putnam divorced George in Reno in 1929 after he met aviation pioneer Amelia Earhart, whom he married in 1931. Dorothy remarried a month after the divorce.

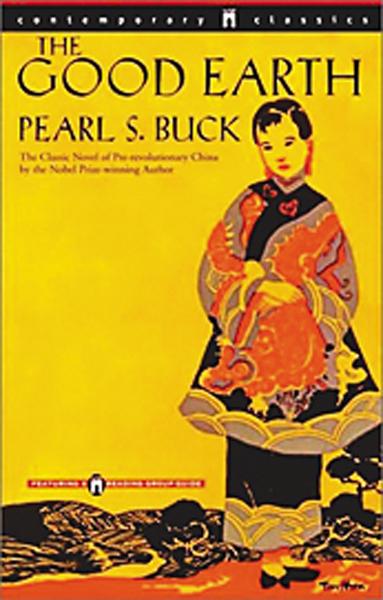

Author Pearl Buck—best known for 1931’s The Good Earth—divorced John Lossing Buck, an agricultural economist, in Reno in 1935. Three years later, she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.

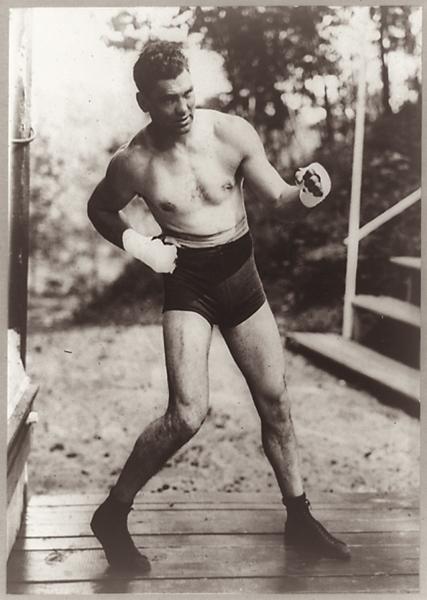

The heavyweight champion during 1919-26 divorced silent film actress Estelle Taylor in Reno in 1931.

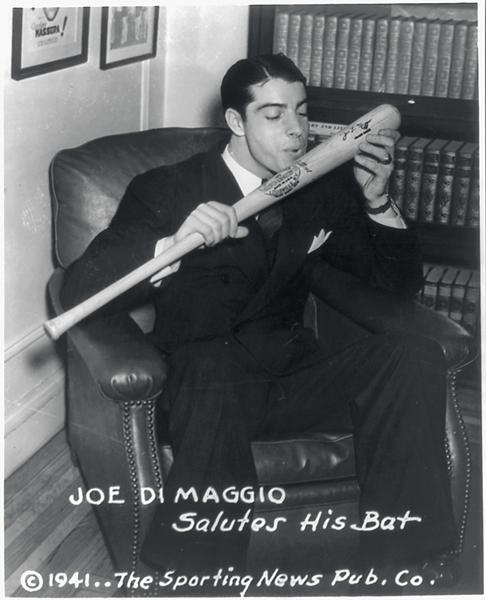

Dorothy Arnold threatened divorce in 1942, telling the Yankee center fielder she would only stay with him if he enlisted in the Army. Yet after Joe enlisted in 1943, she returned to Reno and divorced him.

While the playwright was waiting on his Reno divorce from his college sweetheart Mary Slattery in 1956, he wrote The Misfits, starring Marilyn Monroe as divorceé Roslyn Taber. The actress married Miller in June.

– All images courtesy William L. McGee unless otherwise noted –

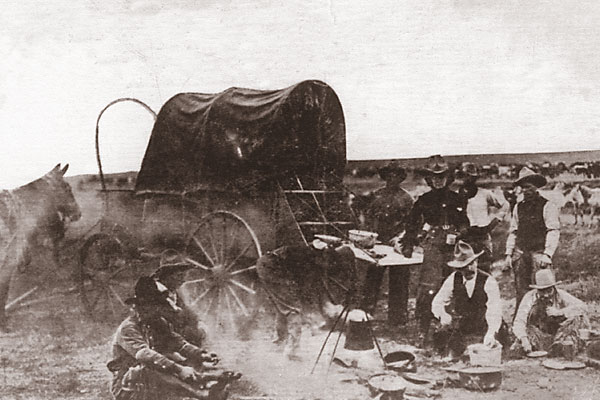

– Courtesy Neal Cobb Collection, Ernie Mack Photos –

– AP Wire photo, Courtesy Special Collections Department, University of Nevada, Reno Library –

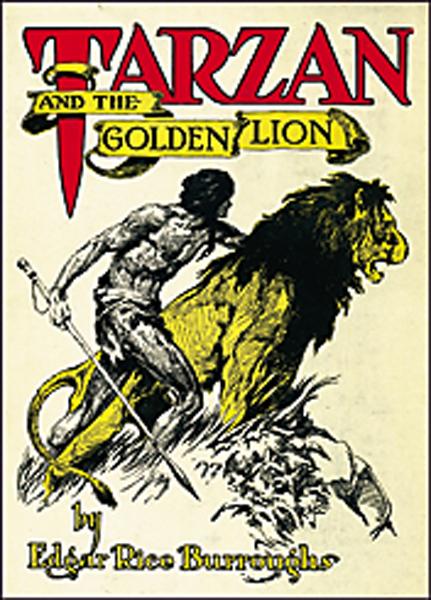

The Tarzan creator divorced Emma Hulbert in Las Vegas in 1934. Meanwhile his sweetheart, Mrs. Florence Dearholt Jr., was awaiting her divorce from Ashton, Burroughs’s producer. She and Ed married on April 1, 1935.

– Courtesy Will James Art Company –