In 1880, Capt. David L. Payne and the boomers began entering Indian Territory with the hope of establishing permanent homes.

Payne was a veteran of the Kansas Infantry during the Civil War, a scout under Gen. Philip Sheridan during the Indian campaigns in the late 1860s, and a member of the Kansas legislature in 1871. He had also guided hunting parties and pioneer trains at various times in his life, but it was his leadership of the Oklahoma boomers that brought him to national attention.

Payne believed that nearly two million acres in the center of Indian Territory known as the “Unassigned Lands” were not allotted to any particular tribe and cited as proof an 1866 treaty in which these lands were surrendered by the Seminole and Creek as a concession to the U.S. government for the tribes’ support of the Confederacy during the Civil War. As intended, the majority of the confiscated lands were given to other tribes, but the Unassigned Lands and large portions of the Cherokee Outlet remained vacant.

Settlement of the Unassigned Lands had become a prickly issue in February 1879, following the publication of an article in the Chicago Tribune by Elias Cornelius Boudinot, a Cherokee citizen, a clerk for the House of Representatives Committee on Private Land Claims and a lobbyist for the Missouri, Kansas, and Texas Railroad. Boudinot encouraged settlement of the Unassigned Lands and proposed legislation that would make the area an official territory of the United States under the name Oklahoma. His appeal was joined by Morrison Munford, owner and editor of the Kansas City Times, who reprinted Boudinot’s thesis. Munford used the volatile term “boomers” to describe a movement still in its infancy yet ready to explode, and the articles in his paper established a common rhetoric for the undertaking. The boomer movement would advocate the settlement of Oklahoma for the ensuing decade.

No Turning Back

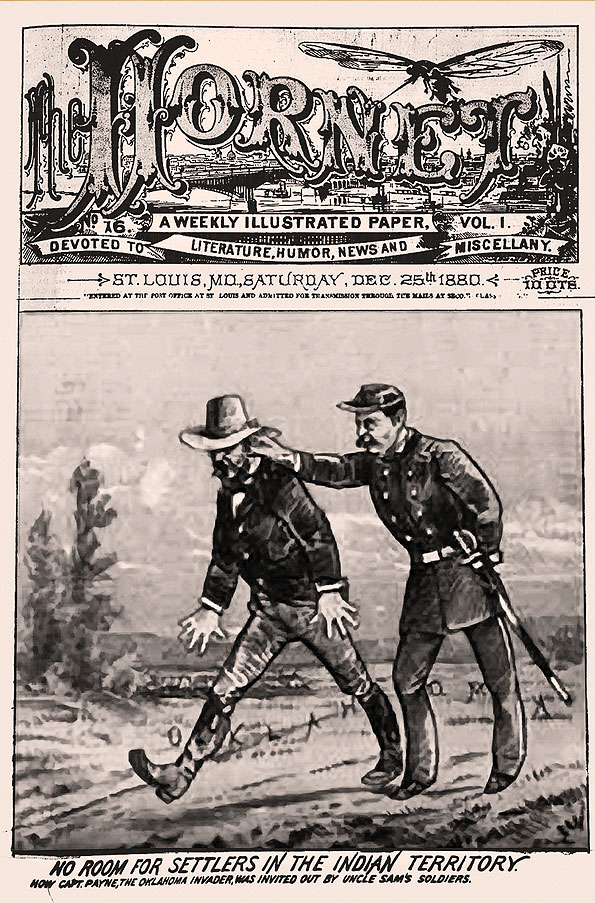

Payne made his first incursion with a small band of would-be settlers in April 1880, founding the settlement Ewing on the site of present-day Oklahoma City. Lieutenant George H.G. Gale and troops of the 4th Cavalry promptly arrested the group and escorted them back to Kansas. Payne returned to Ewing in July with similar results, although this time, Judge Isaac Parker fined Payne the maximum penalty of $1,000 for violation of the Indian Intercourse Act.

The Hornet, an illustrated St. Louis weekly, represented Payne as a disobedient child pulled out of Oklahoma by his ear. For The Hornet, Payne was the “Oklahoma Invader” who had to be forcibly removed by “Uncle Sam’s Soldiers,” suggesting that the entry into Oklahoma violated not only the law but also the will of the American people.

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, a popular periodical with a national readership, followed suit in January 1881, with an article titled “Invading Indian Territory.” Leslie’s sent an unnamed reporter to Payne’s Kansas camp in December 1880 to report on preparations for the next incursion. Payne and the boomers, again characterized as lawless invaders, were reported adopting a military-style organization in preparation to cross into the territory from Hunnewell, Kansas. The suite of illustrations artist Charles Silverton created to accompany the article depicts the militarization of the boomer camp.

In the illustration Drilling in Camp, for example, a company of armed men stand at attention receiving instruction from Payne, or more likely from Hill Maidt, who had been named the military commander because of his past army service. Against a backdrop of covered wagons, with families in attendance and the American flag flying high, they evoke the stalwart pioneers of the Oregon and California Trails. But as Silverton makes clear, these settlers are prepared to seize territory and violate American law by force of arms.

Emboldened by phrases such as “No Turning Back” and “On to Oklahoma” emblazoned on their covered wagons, Payne’s boomers hoped to realize through divine providence their manifest destiny to expand American civilization and its democratic ideals into unsettled Oklahoma, just as pioneers of a generation earlier had hoped for the country as a whole. The readership of Frank Leslie’s, whether or not they supported the settlement of the territory, would have recognized the ideology propelling the boomers as the same that had justified American expansion across North America.

Despite their provocative rhetoric and actions, the boomers engaged in friendly relations with the 10th U.S. Cavalry under Maj. John Joseph Coppinger, who had been sent to escort the boomers back into Kansas if they crossed the border into Indian Territory. Coppinger and the cavalry were invited to attend Sunday services and given preferential seating in the front row. Coppinger had previously warned the boomers of his duty, and the military followed the camp closely from the rear.

A Frontier Hero of Just Renown

Military intervention and inclement weather ultimately stalled the planned incursion that year, but Payne persisted and continued to publicize the efforts of what was now called the Oklahoma Colony, using his growing celebrity as a promotional tool. The former “Oklahoma Invader” became a frontier hero by the mid-1880s, as his supporters advertised his military background and his Western persona.

Payne’s friendship with William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody enhanced his Western celebrity. In October 1880, prior to the failed invasion in late 1880, Payne visited St. Louis, where he engaged in a friendly debate with Buffalo Bill over marksmanship. They tried to best each other at Sportsman’s Park, until Cody finally announced that he could produce sparks from the end of Payne’s cigar with successive shots from his pistol. Of the five shots Cody took, four had the desired effect, but the fifth missed the mark and took off part of Payne’s mustache. The novelty of the incident reportedly impelled Buffalo Bill to make a lithograph of the event, although prints have yet to surface.

Whether Payne actually lost part of his mustache to Buffalo Bill’s errant shot remains questionable, but the event apparently left no ill will between the two. Payne would make an appearance in the program of the 1884 season of the Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, where he was billed as “Oklahoma’ Payne, the Progressive Pioneer” and “The Distinguished Cimarron Scout and ‘Oklahoma’ Raider.”

The program valorized him as both a martyr to the ideal of frontier settlement and a figure of unfailing principles, who struggled against the corruption of unidentified moneyed interests: “To continue this fight against the greed of remorseless capitalists, Capt. Payne has endured hardships few men have been forced to suffer, proving himself true to principle, and a frontier hero of just renown—a man who cannot be intimidated nor swerved by hardships from his purpose and duty.”

In all likelihood, Payne never appeared in the show because of other commitments, but Cody must have recognized the promotional value of “Oklahoma Payne.”

In the previous year, on November 10, 1883, the sensational tabloid National Police Gazette had also remarked that Payne was “doubtless one of the principal figures of the great West” and “an intelligent, active, faithful worker in any cause he espouses, but given to severe hardship and frontier life, in which he has become famous as scout, guide, and soldier.”

The London Daily News, echoing the sentiments of the Wild West program, explained that Payne and his followers had “found themselves heroes, for the West looked upon them as sufferers from the despotic power of the Government.”

For the propagandists of the boomer movement, Payne’s attempt to settle the last frontier in the West placed him in a pantheon of scouts and trailblazers that included Kit Carson, Wild Bill Hickok and Buffalo Bill. His mother was said to be a cousin to Davy Crockett. Payne’s redoubtable constitution and frontier pedigree, when paired with the boomer’s skillful appropriation of the rhetoric of Manifest Destiny, added to his perceived legitimacy and that of his cause.

The boomer leader’s reputation ultimately hinged on the creation of Rock Falls, the briefly occupied settlement Payne founded with approximately 600 of his followers in May 1884. Located near the Chikaskia River in present-day Kay County, the town boasted a school, a drugstore that sold liquor and a printing office for their newspaper, the Oklahoma War Chief.

The only image of Rock Falls produced for public consumption was that of Payne’s cabin, nestled in a densely wooded area that evoked almost a century of log cabin imagery in American culture. By the 1880s, the log cabin had come to symbolize both the settlement of the American wilderness and the humble origins of great political leaders, including Andrew Jackson, William Henry Harrison and Abraham Lincoln.

The association of the log cabin with Daniel Boone, the father of westward expansion, only solidified its role in American historical memory. Payne’s cabin in the woods acknowledged his place in that national mythology and furthered the boomers’ desire to see their leader placed among the pantheon of frontier heroes.

The Wichita Beacon expressed this sentiment in November 1884, when it predicted that Payne’s “name will be forever linked with the history of the state that is sure to be created in the country south of us. What Daniel Boone is to Kentucky, Dave Payne will be to Oklahoma.”

By this time, however, Payne’s Rock Falls had already met its demise. On August 7, troops burned the settlement, arrested the leaders of the movement and escorted the boomers out of the Cherokee Outlet. Payne was tried in Topeka for conspiracy but won a brief victory when district judge Cassius G. Foster dismissed the indictment.

On November 28, while preparations for another incursion were under way in Wellington, Kansas, Payne suddenly died of heart failure. The movement faltered momentarily but quickly regained momentum, with Payne in the role of martyr to the cause.

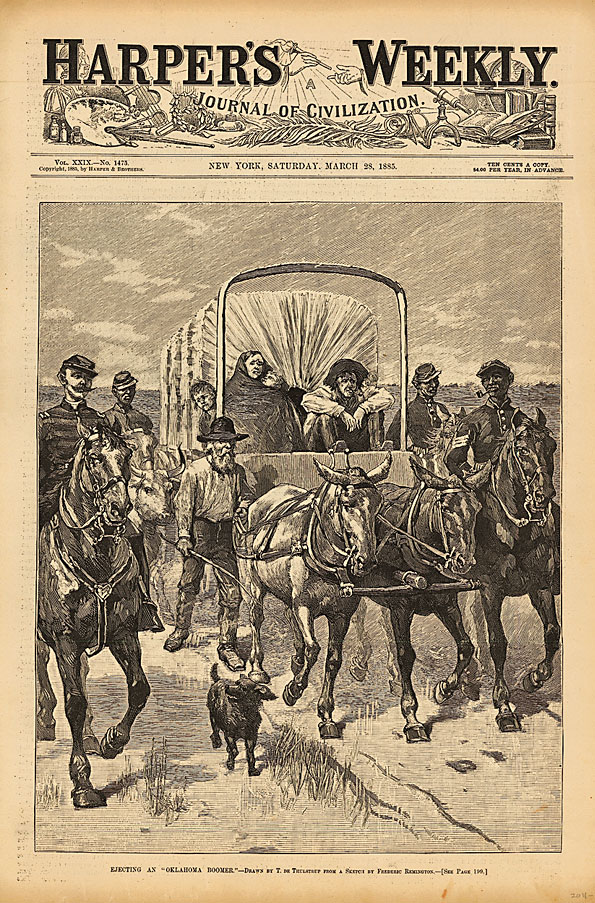

Ejecting an Oklahoma Boomer

In the months following Payne’s death, Capt. William L. Couch assumed leadership of the boomers and led another incursion in December 1884, which resulted in the establishment of Camp Stillwater (on the site of present-day Stillwater, Oklahoma).

Colonel Edward Hatch, commander of the 9th Cavalry Regiment, a black outfit popularly known as the Buffalo Soldiers, sent a detachment from Fort Reno under Lt. Matthias W. Day to remove Couch. Harper’s Weekly reported that 400 armed boomers met Day and stated their intentions to remain on the land. Hatch, after consulting with Day at Fort Reno, subsequently gave Couch 24 hours to leave and threatened to call 12 companies to ready, if necessary.

Rather than fire on the boomers, Hatch cut their supply line from Kansas, forcing them to surrender. Frederic Remington’s Harper’s Weekly drawing, Ejecting an “Oklahoma Boomer,” characterized the removal of the boomers as a somewhat comic affair.

Remington lived in Peabody, Kansas, in 1883-84 and had witnessed the travails of the boomers during his own brief excursions into Indian Territory. The drawing also represented one of Remington’s first depictions of Buffalo Soldiers and recognized their role in policing Indian Territory.

Although Remington cast the Stillwater affair as largely peaceful,

the popular press frequently emphasized the violent tendencies of the boomers. Harper’s reported, “from the accounts that come to us there is likely to be an outbreak and bloodshed at any moment.”

Printed in Frank Leslie’s only months before the first land run, James Ingram’s 1889 illustration represented a potentially lethal confrontation between military scouts and boomers.

With Payne’s death and Couch’s increasingly frequent trips to Washington, D.C. to publicize the boomer cause, the movement became disorganized.

The Wichita Board of Trade, in hopes of reigniting the plans for Oklahoma settlement, approached a celebrity even more popular than Payne to lead the boomers into Oklahoma.

The Psychology of Show Business

The Wichita Board of Trade needed a charismatic figure to lead the boomers out of Kansas anew and proposed one man take charge: Maj. Gordon William Lillie, better known by his stage name Pawnee Bill.

The showman agreed and arrived in Wichita on December 22, reportedly to an ovation and a brass band. By the next day, he had already planned a new invasion of Oklahoma.

As Lillie later explained, the Wichita Board of Trade had hired him for his promotional skills: “I began to work on the idea again, applying the psychology of show business. They employed me to promote the Boomer project, guaranteeing all expenses and immunity of harm.”

A consummate showman, Lillie used boisterous, theatrical rhetoric to inspire the boomers and promote the movement. “We will have 10,000 men ready to move,” he reported in January 1889, “and I don’t see how the 1,500 soldiers—the largest body that can be gotten together—will be able to stop us. There is now no longer any question about it—the men are ready to move. We will go on February 1 and we will take Oklahoma—Congress or no Congress.”

Harry Hill and other boomer leaders were more cautious and urged Lillie to await the fate of the Springer Bill, which supported the opening of the Unassigned Lands and was currently being considered by Congress.

Despite Lillie’s inflammatory rhetoric, Hill must have appealed to his sensibilities, and the invasion was delayed. The Springer Bill stalled in the Senate, but an amendment to Indian Appropriations Act authorized Pres. Grover Cleveland to proclaim the lands open for settlement. This appropriations bill passed, and Pres. Cleveland signed it into law before leaving office—though his successor, Pres. Benjamin Harrison, ultimately issued the proclamation.

Lillie credited the newspaper campaign led by Wichita Eagle Editor Marsh M. Murdock for prodding Congress: “It was the unceasing advertising which that great newspaper gave the project which brought the tens of thousands of settlers to the border, to settle the territory in one big stampede, one of the most spectacular and epochal events in the history of the United States.”

Settlement would occur through a race for the land, heightening the spectacle of the event. On April 22, the day of the run, Lillie moved 3,000 settlers to Col. George Washington Miller’s 101 Ranch in the Cherokee Outlet. Lillie approached his role in the event as another opportunity for showmanship, riding the 20 miles to the area around modern-day Kingfisher in 65 minutes. He later admitted, “the run was great publicity. The press of the whole country was full of it. This helped the show business wonderfully.”

Harper’s Weekly opined of the 1889 run that “in its picturesque aspects the rush across the border at noon on the opening day must go down in history as one of the most noteworthy events in Western civilization. At the time fixed, thousands of hungry home-seekers, who had gathered from all parts of the country, and particularly from Kansas and Missouri, were arranged in line along the border, ready to lash their horses into furious speeds in the race for fertile spots in the beautiful land before them.”

Within hours of the run, Guthrie, Oklahoma City and Kingfisher, each of which had boasted little more than a train station and a land office the day before, became settlements of thousands and, within a few months, thriving cities and towns.

By 1890, Pawnee Bill was calling himself “the Chief of the Oklahoma boomers,” and his 1902 biography dubbed Oklahoma “a living monument to Pawnee Bill.”

No Parallel in Human History

The 1889 run, as well as the four that followed, was a federally sponsored Darwinian contest, in which those with the fastest transportation, the greatest endurance and perhaps some foreknowledge of the lay of the land succeeded in securing a location. Calls for statehood began soon after the conclusion of the land runs.

The statehood ceremony, held on November 16, 1907, in Guthrie, included a mock marriage in which Indian Territory was pledged as the faithful bride to Oklahoma Territory. The notion that Indians had become the domestic dependents of the American presence in Oklahoma, suggested 18 years earlier in Thaddeus Mortimer Fowler’s panoramic map of Oklahoma City, was given ceremonial form.

Given the spectacular, and sometimes theatrical, nature of Oklahoma settlement, it is of little surprise that the ceremony accompanying statehood would dramatize the climax of westward expansion. Boomers for settlement and statehood, from David Payne to Pawnee Bill, had employed spectacle as an ideological device for furthering their cause.

Collectively, they constructed a common mythology in print and image that positioned Oklahoma as the apogee of American expansion: an American Canaan promising limitless wealth and possibilities, settled in a series of spectacular land runs with no parallel in human history and transformed seemingly overnight into the site of a modern, progressive society.

Mark Andrew White is the Wylodean and Bill Saxon director of the Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art at the University of Oklahoma. His article is an edited excerpt from Picturing Indian Territory: Portraits of the Land that Became Oklahoma, 1819-1907, published by University of Oklahoma Press and edited by B. Byron Price.