A reckless breed known as mountain men left an indelible impact on western history. Reckless doesn’t accurately describe them. The reckless ones didn’t last long in the wild untamed land. Alone or in small groups, they ventured out across the wide Missouri and into the trackless Rockies that because of their glittering snow, Indians called the “Shining Mountains.”

They numbered no more than a thousand, maybe two, and their heyday lasted less than twenty years but these aristocrats of the wilderness can never be forgotten or ignored. They were uniquely American, spending most of their lives in the mountains. No other country has produced such a figure or “critter” as they preferred.

Not many were literate so the details of their adventures are scarce and few records were kept. Their exploits may have been exaggerated and they may have been mythologized all out of proportion (which many of them would have enjoyed).

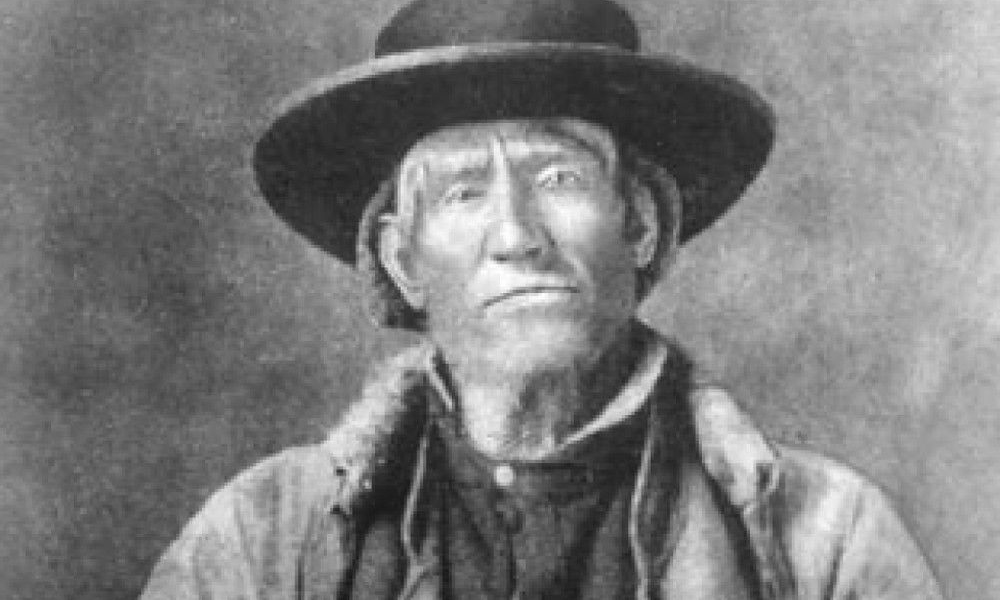

The legend began in 1822 when an ad appeared in a St. Louis newspaper that began with: “To all enterprising young men…” It attracted a small group of adventuresome young men who would become American legends including Jedidiah Smith, Hugh Glass, Jim Bridger, David Jackson, Mike Fink, Antoine Leroux, Jim Clyman, Tom Fitzpatrick, Jim Beckwourth and Jim Kirker.

The odds of a mountain man or free trapper living to a ripe old age were slim. In 1856 Antoine Robidoux could account for only 3 out of 300 who went into the Rockies some thirty years earlier. James Ohio Pattie recalled only 16 out of 160 survivors in only one year in the Gila River country of Arizona. Ewing Young led a party of 24 trappers into Arizona for the 1827-1828 hunt and lost eighteen killed by Apache. Darwin’s theory of survival of the fittest was never more pragmatically proved than during the two decades that marked the heyday of the mountain men. If his top knot didn’t get removed by some hostile warrior there were many other hazards that could cause a trapper to “go under.”

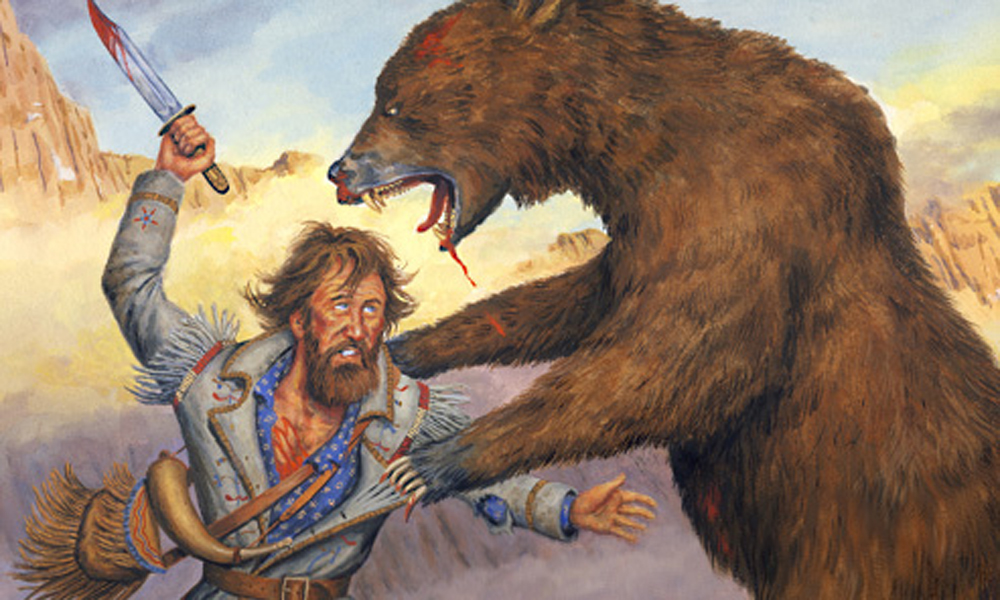

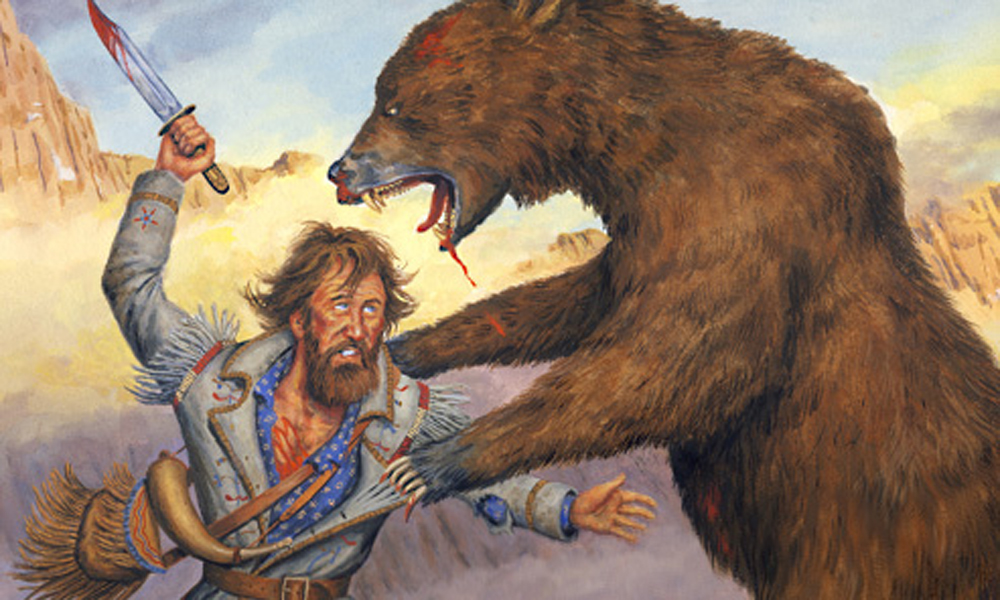

Grizzly bears were numerous and at that time had absolutely no fear of man. Trappers reported seeing as many as 220 in a day, sometimes in bunches of 50 or 60. Given a mountain man’s penchant for exaggerating; half of that many would be a formidable force to reckon with. Weighing a thousand pounds and more, they were agile as a cat and able to run up to speeds of 35 miles an hour. And they had an ornery disposition to match.

There were also many other ways of shortening their life expectancy including freezing to death in the mountains, accidents and drunken brawls at the rendezvous, and dying of thirst in the desert. Crossing a desert might reduce him to eating insects. One trapper wrote: “I have buried my hands into an ant den then greedily licked ‘em off.”

Others reported making stew with the ears of their mules or soaking their moccasins until they were soft enough to eat. Some crossed the line into savagery. Charlie Gardner got the nickname “Phil” because he hailed from the City of Brotherly Love, went into the mountains with a companion and the two were lost in a violent blizzard. They were given up for dead by the others but a few days later Gardner rode into camp alone, pulled a piece of a human bone out of his pack and tossed it on the ground exclaiming “There, damn you, I won’t have to gnaw on you anymore!”

Thereafter his friends referred to him as “Cannibal Phil.” It was said that sometime later he spent another rugged winter in the mountains; this time the object of his culinary work was his Indian wife.