The American West begins in St. Louis, Missouri. Many entering the frontier started their journeys by riding on steamboats to jumping-off areas in Missouri. Riverboat disasters were all too frequent.

On the frigid night of January 3, 1844, the Shepherdess was steaming upstream roughly three miles from St. Louis, its destination. Steamboats of the period had private accommodations for those able to pay, while general passengers were provided separate women’s and gentlemen’s cabins. Most of the roughly 70 passengers shared these two parlors on the first deck. By 11:00 p.m. many of the ladies and gents had retired for bed. In the men’s parlor, a few gentlemen sat around a stove for warmth.

The air was filled with the sounds now familiar to the passengers—chugging of the engines, churning of water, water slapping against the bow, creaking of timbers, people coughing and the noises of livestock on the deck.

The peaceful night was suddenly rent by a loud scraping and the sounds of cracking timbers. The boat had hit a snag of timber in the river. After a brief pause, the air resounded with alarms, screaming children and the moaning of the stricken vessel as it broke into splinters.

The boat lurched and filled with freezing water, which reached the lower deck in less than two minutes. Captain Abram P. Howell entered the ladies’ cabin and assured them they were safe. Afterwards, he was washed overboard while ringing an alarm bell. Three minutes after the crash, the boat was flooding to the upper decks, and the passengers were scrambling for safety by any available means.

Passenger Robert Bullock, of Maysville, Kentucky, immediately responded to the crash by going from stateroom to stateroom, looking for women and children to evacuate. He took his fellow passengers to the hurricane roof, which, by this time, was the only part of the Shepherdess above water. With many of the women in their night clothing, the samaritan surrendered his fine wool coat to one lady during his several rescue missions. Included among those he rescued was Col. Joseph H. Wood’s “Ohio Fat Girl,” an entertainer in a traveling “freak show.” The eight-year-old girl weighed roughly 250 pounds.

When the Shepherdess, by this time powerless and drifting downriver, hit a second snag, the impact threw Bullock overboard. He swam the dark, freezing currents and found footing on the Illinois side. There, Bullock found two women who had been landed by a skiff, but were freezing. As the ladies drifted off to sleep, he feared that slumber would bring death to them, so he struggled to keep the suffering women awake. He helped the pair get to safety at Cahokia Bend.

Forty persons, including Capt. Howell and one of his 11 children, reportedly perished in the accident. Only the efforts of unsung heroes, like Bullock, kept the death toll from being higher.

Survival Tip: How to Keep Warm after Nearly Drowning

The sunken ship put all of those who went into the water into a serious survival situation. After swimming to land, Robert Bullock found himself keeping two ladies alive while awaiting rescue. The nature of 19th-century clothing helped, as everyone was likely wearing woolens. Even when wet, such clothes retain some of their insulating properties.

Bullock waking his fellow castaways once on land might have been prudent. If they were hypothermic, keeping them active was good; otherwise, it could have had negative effects. His best option was to keep the survivors huddled together to share body heat.

Bullock greatly added to the risk of his fellow passengers by forcing them to strike off into the dark to find help. This survival tale fortunately ended happily, despite Bullock’s risky choice.

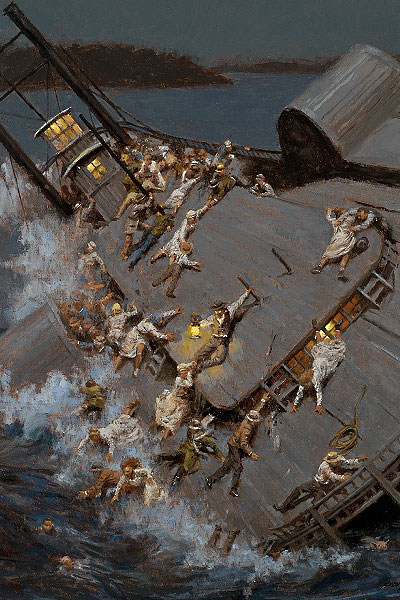

History in Art

By Illustrator Andy Thomas

I show the moment the boat hit the second snag and tossed Robert Bullock and others into the Mississippi River. The second snag caused the boat to momentarily list severely to its larboard side. The steamboat is modeled after artist Gary Lucy’s painting of the recovered steamboat Arabia; it was of similar tonnage and close to the same time period as the Shepherdess (a contemporaneous newspaper engraving depicted the Shepherdess as a sidewheeler).

Terry A. Del Bene is a former Bureau of Land Management archaeologist and the author of Donner Party Cookbook and the novel ’Dem Bon’z.