The rise of Charlie Russell, and the wife who made him a star.

This triumphant moment had all begun with a marital spat, Nancy liked to say. Charlie had accepted a commission in 1897 to paint little watercolors on 125 menus for a Christmas dinner at the Park Hotel in Great Falls. The payment was atrocious—twenty dollars for the lot. “Right there, we had a real fuss. He worked days on them and I thought he should have at least as much as the cook and waiters would get per day. He thought so too but did not have the courage to ask for enough for us to live on and save a cent.”

Russell’s art dealer in Butte, Montana, Charles Schatzlein, told Nancy that Charlie did not charge enough, and since he was incapable of asking for more, she must. By 1898, she was doing exactly that—negotiating with buyers personally, and ratcheting up prices. That spring a lady ordered “a water color of a steamboat stopped by buffalo crossing the Missouri River,” Nancy recalled:

When finished, it was a beauty…. Charlie hoped she would pay $25.00. We needed hay for the horses and I wanted a new cook stove. So, I asked if I couldn’t deliver the picture.

“Now, Mame, if you ask more than $25.00 for that picture, she won’t take it and we need the money.”

Our lady saw the beauty of the picture and was much pleased.

“How much does Mr. Russell want for it?”

With a choking feeling, I said, “35.00.”

“Just wait and I will give you a check.”

Glory be! I had $10.00 toward the new cook stove. When I gave Charlie that piece of paper, he got as much of a thrill out of it as he did when handed a check for $30,000.00 in 1926, when he quietly said, “I can’t read so many figures. What do they say?”

Such was the arc of Russell’s career from Nancy Russell’s perspective. The journey that got them to thirty thousand dollars was her contribution.

Broke in Cascade

Art remained a hard sell in Montana, and Russell was so sufficiently discouraged that an old acquaintance, encountering him in Cascade sitting in the shade of Ben Roberts’s harness store, was struck by his pessimism. “He was getting nowhere, the range cattle business was dead,” and things were at a standstill, John Barrows recalled.

Charlie had no intention of adjusting to change by pitching hay, mending fences, or milking cows. Art was his only option. But if his art was a business, as long as he had been cowboying, it had been a nonprofit one. Now Russell had to earn a living selling what he used to give away. When he and Nancy married in 1896, he was broke. He might come from a privileged background, but his current circumstances were inauspicious.

“Things had gone very much awry with Charlie’s work after we were married,” Nancy recalled. “He had had no orders for pictures and no chance in Cascade to meet buyers,” though “his credit was good, so we were eating regularly.” Things would have to change.

The Nancy Era

A new era was about to begin in marketing Charles M. Russell—the Nancy era. Sentiment, modesty, and friendship would have to yield to sound business principles. Montana could still be the base of operations, but with St. Louis showing the way, Russell’s work would have to find a national audience. The two streams had coursed along separately, Montana providing subject matter, some sales, and local appreciation; St. Louis, the prospect of more substantial patronage and national recognition. The streams converged in 1896; thereafter, everything flowed through Nancy.

Schatzlein is often considered Russell’s first art dealer—that is, the first individual with a business that made the selling of Russell art an ongoing activity. Schatzlein, who had come to Butte in 1881 “penniless but ambitious,” had opened a paper-hanging shop that expanded into the Schatzlein Paint Company, selling paint, wallpaper, glass, custom framing, artists’ supplies, and pictures. Schatzlein was an ardent amateur artist himself, and he recognized in Russell’s work a special gift. Consequently, he contented himself with painting replicas of Russells and signing them as such. But more than that, his paint store by 1897 was a venue for Russell art. William Bleasdell Cameron, traveling on assignment for Western Field and Stream, a new sportsman’s magazine published out of St. Paul, was captivated that May when he saw some Russells on display at a Butte hotel. When he inquired after the artist, he was immediately directed to Schatzlein’s store.

After seeing Schatzlein’s Russells, Cameron made a beeline to Cascade to meet the artist and followed up with a two-week stay in June. The result was a contract signed in Great Falls on September 30, 1897, committing Russell to paint and sketch “a pictorial history of western life”—twenty black-and-white oils at fifteen dollars each and twenty pen-and-ink drawings for a total of twenty dollars—the paintings to be reproduced in successive issues of Western Field and Stream and collected in one book, the pen-and-inks in another, with Russell owning “a one-third interest in … all profits which may arise from their sale.” Nancy, signing herself as Mamie Russell, witnessed the agreement. Perhaps it would bring Russell needed exposure of the sort he had enjoyed when Waiting for a Chinook created a minor sensation ten years before. Somehow he had to catch the public’s eye again.

Owen Wister, in thanking John Beacom for a copy of How the Buffalo Lost His Crown that December, referred specifically to Russell’s magazine appearances: “His work is not unknown to me because a friend occasionally sends me ‘Western Field-Stream’.… He has undoubted gift; all he needs (so far as I’m able to judge) is to work out into his own complete style . . . it has been a plan to send an MS to Russell sometime to see what he can do with it.…”

In 1911, two years after Remington died, Russell was tapped to provide forty pen-and-ink sketches to complement ten previously published Remington drawings in a new illustrated edition of Owen Wister’s already classic The Virginian. The commission must have given Charlie satisfaction and Nancy a sense of cosmic vindication. She had been in charge of her husband’s career since The Virginian first debuted in 1902.

The press proclaimed him Remington’s successor and, some thought, his superior. “Comparison with the late Frederick [sic] Remington is inevitable,” the New York Evening World commented, “so we may as well have it over at once, and say that Russell is slightly in the lead and still going strong.”

The Great Betrayal

By 1907 the Great Falls printing firm of W.T. Ridgley was the leading purveyor of Russell prints, calendars, and postcards. The Ridgley postcards, especially a series of cartoon sketches in color done by Russell in 1907, caught the fancy of most who saw them and had an interest in things western. A traveling Will Rogers sent a selection from Butte to his future wife, noting that Russell “is the greatest artist of this kind in the world Remington is not in it with him.”

By January 1906 Russell and Charles Schatzlein were partners in the W.T. Ridgley Printing Works, which advertised itself as “Manufacturers of the Russell Calendars of Western Life.” Subsequently, Nancy was listed as secretary, Schatzlein as president, and Charlie, in 1911, as vice president. It is hard to know what these titles meant in practice, since Ridgley was eased out of his own firm in 1909, and what Schatzlein regarded as the great betrayal had already taken place.

Inevitably, the popularity of Russell art attracted competitors, including Brown and Bigelow, the nation’s leading calendar company. Based in St. Paul, it had been in the chase for a while, copyrighting Russell’s The Bolter [No. 3] in 1904, for example; in 1908, it moved to establish a monopoly. Nancy’s lawyers drew up a contract on April 21, following a visit to Great Falls by Herbert H. Bigelow. “We have not as yet seen Mr. Schatzlein, so I cannot tell what we will do until I talk with him,” she wrote in the cover letter. “I think it will be alright so that is why I am sending these to you before we see him.” Bigelow returned the signed contract post haste, with a few modifications. Most important, he moved the starting date from December 31 to May 1, 1908, permitting no time for Ridgley to issue its line of 1909 Russell calendars. Brown and Bigelow wanted immediate exclusive right to produce Russell calendars and advertising. Brown and Bigelow agreed to buy the copyright to “at least” six paintings each year (“and four for the balance of 1908”). As long as Brown and Bigelow upheld their end of the agreement, Russell was barred from allowing any new paintings to be used for calendar or advertising purposes. The contract ran to December 31, 1913. Russell’s contract with Brown and Bigelow, like Remington’s with Collier’s Weekly, provided immediate financial security; though at half the price for half the number of paintings, it was not nearly as lucrative. Still, five hundred dollars per copyright was a considerable advance over the fifteen dollars paid by Western Field and Stream.

Success had come at a price. Schatzlein, kept in the dark by Nancy during the negotiations, wrote her on April 29: “I consider it a dirty trick,… Our little business won’t be worth 50 cents on the dollar. I wish I had an idea a year ago that something of this kind would turn up. … It is a case of the Big fish eating the little ones. …”

Such a wounded, angry letter from an old friend prompted Charlie to reply personally. His tone was conciliatory as he wrapped Nancy’s rationalizations in his own determination to steer clear of business dealings in the future:

Now Im not the kind of man that would saw of [f] the bad end to a pardner but this year looks like a bad one for pictures I havent aney orders now an with nothing in sight the Biglow propision looks like a life saver to me I know you are in plenty on our Calender Co but as the contract dont bar postle cards theres a chance [to] make some out of them an there is several pictures in this town to be had an I think it could be run all right till some thing can be don I would like to sell out if all of us could quit eaven business is a game I aught to keep out of an you can bet your stack Il buy no more chips.

The letter was unillustrated, but the envelope bore a water-color of a man treed by a bear, perhaps in acknowledgment of Schatzlein’s complaint about the big swallowing the little, or perhaps to express Charlie’s own embarrassment at the predic-ament in which business had placed him.

In one respect, Schatzlein was absolutely wrong. He had warned Nancy at the time that the exclusive contract with Brown and Bigelow was a bad deal for Charlie: “In the long run you will be the looser [sic] by it.” The opposite proved true. In the wake of the national exposure provided by Brown and Bigelow calendars and prints, Russell’s prospects soared. Showing her business acumen, Nancy had insisted on a critical provision in the contract: the originals of all paintings chosen for reproduction were to be returned in good condition within three months. This created a body of major paintings available for exhibition and sale that were already familiar through color reproductions. Brown and Bigelow would spread Charlie’s fame, and the Russells would pocket the rewards.

Charlie’s exhibition at the Folsom Galleries in 1911 was a breakthrough: a one-man show at a major New York gallery. “The West That Has Passed,” featuring thirteen oils, twelve water colors, and six bronzes, opened on April 12. It signaled Russell’s artistic coming of age. Previously, Nancy had focused on increased productivity and rather arbitrary price increases to advance their income; New York taught her that exhibition-quality pieces showing Russell at his best provided a surer path to prosperity. In that respect, the Brown and Bigelow contract paid off handsomely. Eleven of the oils listed in the catalog and half the watercolors had been reproduced as calendars and prints. The attention the exhibition attracted was everything Nancy could have hoped for. They returned to Great Falls as conquering heroes.

Pay Dirt

In the spring of 1925, Edward L. Doheny, whose vast wealth rested on Los Angeles oil, had bought Russell’s The Wolf and the Beaver, a parable in paint about the fate of those who live outside the law as pariahs shunned by the virtuous and hardworking. The irony was too rich to fabricate, Doheny having gotten mired in the Teapot Dome scandal, as it came to be known, in 1924. He would eventually be cleared of wrongdoing, but his name was besmirched. That year, Will Rogers quipped that Charlie Russell was the only man in oil who remained pure. Perhaps the Old West offered Doheny an escape from his troubles. In August 1926 he would add a cast of Russell’s largest bronze, Meat for Wild Men, to complement the paintings in his Western room. By then a Russell mural was in place.

Nancy deserved the credit. She and Charlie had made a “flying trip” to Los Angeles in November 1924 to begin negotiations. She continued on to Duluth for an exhibition that December while Charlie stayed home to work on the designs the Dohenys required. With the Dohenys it was different. The sum being bandied about was enormous—thirty thousand dollars for a two-panel mural 2½ × 43 feet. This was the richest prize she had ever tried to land, and she was not about to let it get away.

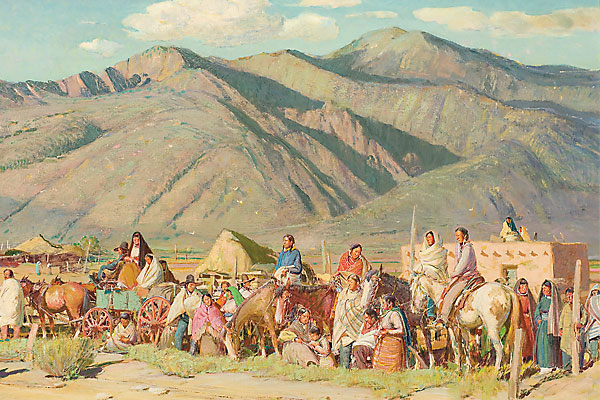

In his designs for the Doheny mural, Russell offered four main themes connected by bits of landscape—a roundup, a scene with wildlife and a distant stagecoach, a pack train, and (borrowing from his painting for Philip Cole, Pay Dirt) a party of prospectors panning for gold. The idea was to illustrate the development of western commerce, culminating in the oil derricks that were the source of Doheny’s fortune. Whether or not Charlie rebelled at including them—he had made it clear that he did not like wildcatters any better than sheepherders or dry-land farmers—include them he did, in the distance at the very edge of one drawing. This tribute to the oil industry was so muted that it does not constitute a separate theme. It simply extends the idea of prospectors striking it rich in California. Russell had made a compromise without really compromising and had emerged with his integrity intact.

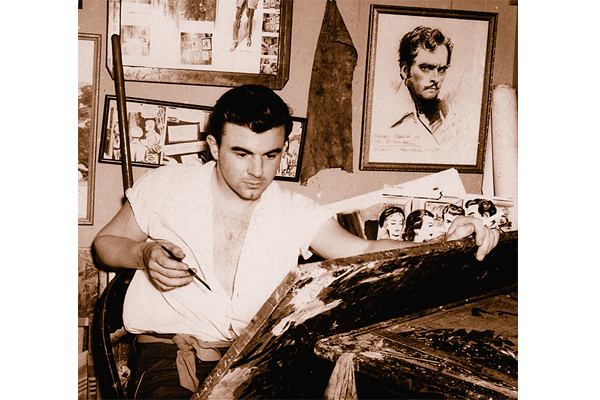

So, tired and enfeebled by his goiter condition, short of breath and energy, given to spells of hacking coughing, Russell in the spring of 1926 pressed on to finish the Doheny mural.

A year before he died, Charles Russell in his labored hand wrote out in pencil “A fiew wordes about myself.” “I am an Ilistrater,” he said, “thair are lots better ones but some worse aney man that can mak a living doing what he likes is lucky an Im that. Aney time I chash in now I win.”

This was a man at peace with himself and satisfied with what he had accomplished in life. He also, in a newspaper interview the same year, paid tribute to Nancy: “After we were married my wife said she was going to change me—and she did. The worst fight we ever had was in 1897 when she asked $75 for a canvas, which I thought highway robbery—and got it. I was willing to sell it for $5, but she insisted that we had to eat. From that time on she has sold all my paintings. It used to worry me, the prices she asked, but she always gets what she goes after.… We are partners. She is the business end and I am the creative. When we travel she takes care of everything. She lives for tomorrow and I live for yesterday; so it is the combination which brings things today.”

Will Rogers put the case for Nancy succinctly: “She enlarged his Market from what had been purely local Consumption to one which embraced two Continents.”

A few months before Charlie’s death on October 24, 1926, Nancy gave her own take on things. That April she heard from a childhood acquaintance who remembered her from the hardscrabble years in Helena. “Yes,” she replied, “I am, or was, the little girl you were talking about, way back in ’94.… I, as you know, married the only Charles Russell in the world and my life has been very full of romance, which they like to make moving pictures out of, only mine happens to be real.”

Charlie finished the Doheny mural about the time Nancy was writing. Their journey to thirty thousand dollars was complete. Her unshakable confidence in the artistic importance of Charles M. Russell was the foundation of their success. He may have frustrated her by taking for granted the manner to which he was born and to which she aspired, and by showing no real interest in promoting his art or himself. But she never for a moment doubted his gift.

Excerpt by Brian W. Dippie, professor of history at the University of Victoria, British Columbia, from Charles M. Russell: A Catalogue Raisonne, published by the University of Oklahoma Press. Purchase this book from your local bookstore, via OUPress.com or by calling 800-627-7377.