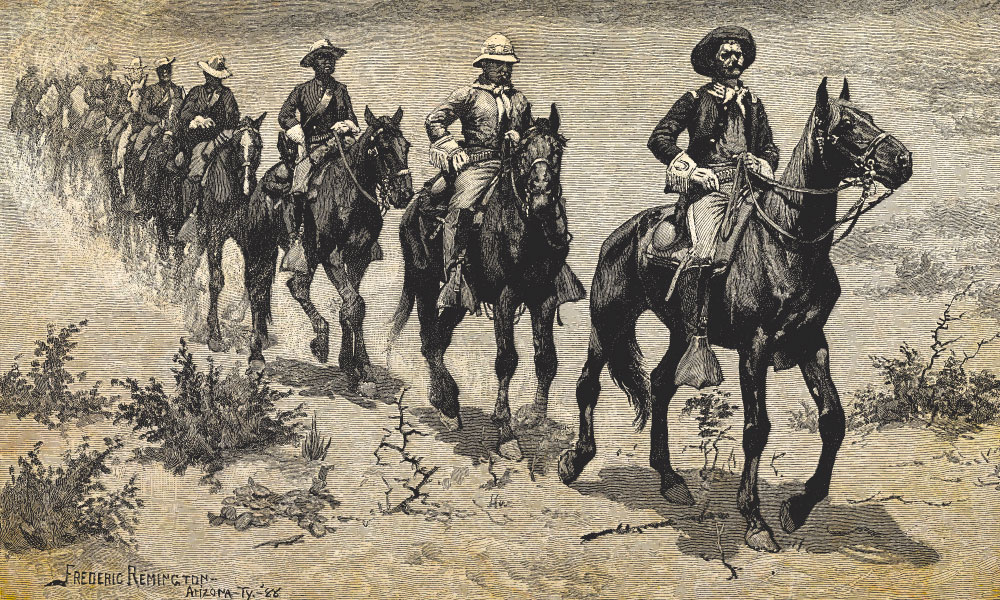

“He doted on stories of his father’s daring exploits in Virginia and Louisiana” as a Civil War Union officer. So wrote renowned historian Peter Hassrick of one of his favorite subjects—Frederic Remington.

The same might be said of the son of another veteran of the bloody conflict that tore the nation asunder from 1861 through 1865, but the patriarch of this man’s family wore Southern gray. This descendant of a Confederate cavalier bore the fanciful name of Powhatan Henry Clarke.

– True West Archives –

The remarkable paths of Remington and Clarke would cross in the Territory of Arizona as young men—one an up-and-coming artist and the other a courageous cavalry officer—and evolve into a close and mutually beneficial friendship that was cut short too soon.

Born on October 4, 1861, in upstate New York, Remington grew up on the martial tales spun by his staunch Republican father “Pierre” and his father’s comrades. Young Fred must have been in his glory when as a teenager he attended a military prep school in Vermont. He went on to a short-lived academic stint at Yale where at 180 pounds, an impressive weight for the time, he joined the football team. Athletics, horseback riding, and pen-and-ink sketches were also favorite pastimes that eventually put Remington on a path that he and his family could not have imagined.

While “Yankee-reared” Remington began to chart his unexpected career in art, the “Rebel-bred” Clarke, who was born on October 9, 1862, followed a different star. Perhaps because of the political connections of his Irish grandfather, who had been an antebellum federal judge, Clarke secured an appointment to the United States Military Academy. He began his “plebe summer”

in 1880.

During the four years that followed as a West Point cadet, Clarke proved a less-than-diligent scholar. As a result of his poor marks, he ranked last in his class of 37 upon graduation in 1884. Like George Pickett and George Custer before him, he was the “goat” of his class.

For graduates, the higher the academic standing, the better the assignment. This meant the newly commissioned 2nd Lt. Clarke had little choice in his posting. Usually the lower tier of new officers fresh from the Hudson were sent to the infantry but below that was the bottom rung—service with a black regiment. Clarke, a Southerner, found himself the junior officer of Troop K, 10th United States Cavalry during the racist era of Jim Crow, when associating with the now storied “buffalo soldiers” was disdained by most Americans.

After taking traditional post-graduation leave, Clarke reported to Fort Davis, Texas, where his troop was on duty. The Lone Star State had been the home of the 10th for nearly two decades, but not long after Clarke was added to the regimental roster the unit received orders for another station. This time it was to be Arizona Territory.

In 1885, the 10th U.S. Cavalry regiment rode from the Department of Texas to the Department of Arizona, following the course of the Southern Pacific Railroad. As the column took up its march from Fort Davis, Texas, it comprised eleven troops and the band. At Camp Rice, Troop I joined the entourage, and from there the twelve troops continued to their new posts at Fort Whipple outside of Prescott, along with Fort Apache, Fort Thomas, Fort Grant and Fort Verde (Troops I and M).

Field operations provided Clarke and some of his equally untested comrades their first taste of campaigning. The formidable foe, known as the Apaches, included a warrior who was Public Enemy No. 1 to many whites. This was the feared and not little despised Geronimo.

A Harper’s Weekly reporter described Troop K’s actions which “…while scouting in the Sierra Pinitas or Little Pines Mountains, in Sonora, Mexico,” the hard-riding command “came upon a band of hostile Apaches, strongly posted upon an open plateau. In the resulting skirmish one man was killed and another seriously wounded. As Cpl. [Edward] Scott, the wounded man, fell to the ground” Clarke “rushed forward through a heavy fire, took the corporal in his arms and carried him out of the line of battle to a place of comparative safety….This exploit of a Southern soldier risking his own life to save that of a colored comrade, apart from its merit as an act of bravery, is a conspicuous illustration of a phase of Southern character which some Northern people have not yet learned to appreciate.”

In a note penned to his mother, Clarke revealed sentiments contrary to his traditional Southern upbringing. While he previously exhibited little respect for blacks in general, Clarke now challenged: “Do not tell me about the colored troops there is not a troop in the U.S. Army that I would trust my life to as quickly as K troop” of the 10th Cavalry. He concluded, “The wounded Corporal has had to have his leg cut off…. This man rode seven miles without a groan, remarking to the Captain that he had seen forty men in one fight in a worse fix than he was. Such have I found the colored soldier.”

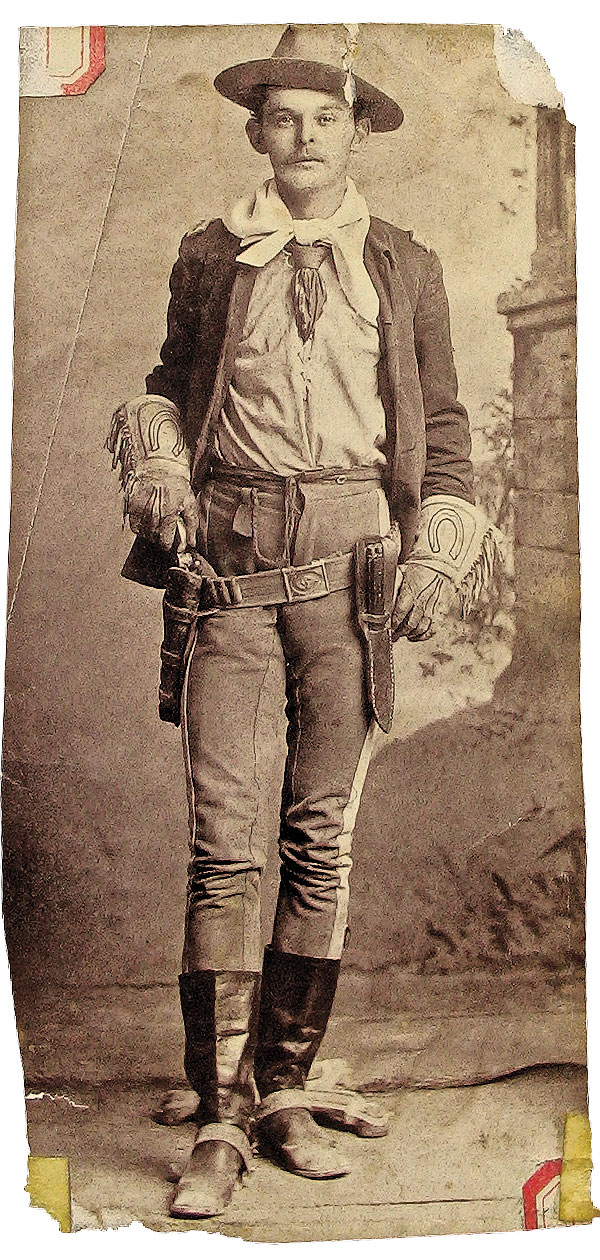

resurfaced after more than 120 years.

– Courtesy George M. Langellier, Jr. –

After learning from Troop K’s first sergeant of this dangerous rescue, the greenhorn Remington made a special trip to interview Scott. At the post hospital Remington recorded that an attendant had led him “over to one [a bed] where a fine tall Negro soldier lay. His face had a palor [sic]…the result of the lost limb. I greeted him pleasantly and told him of my desire to sketch his face….” Comparing a photograph of Scott with Remington’s depiction of this event for the cover of the August 21, 1886, issue of Harper’s Weekly, the likeness is striking.

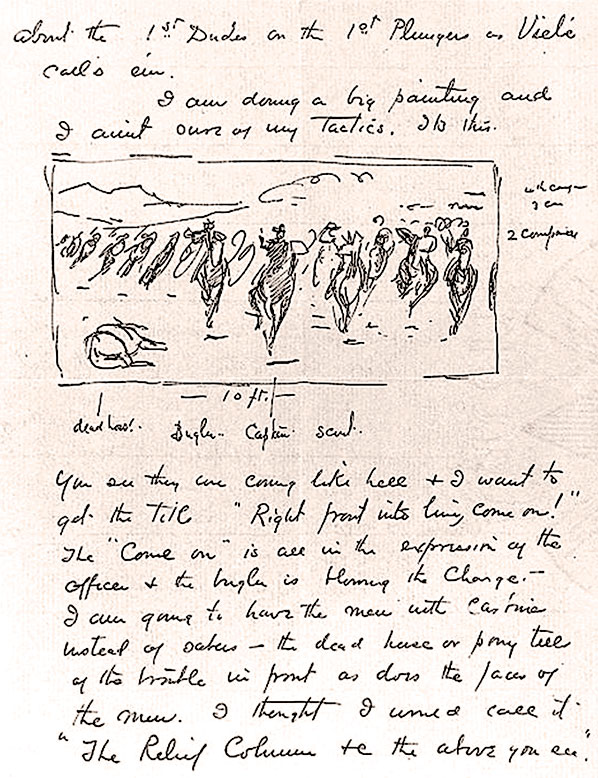

Besides his realistic rendering of Scott, Remington also met and quickly formed a friendship with Clarke. In fact, many missives passed between the two kindred spirits over the years, including one from the budding artist who confided about another excursion to Arizona under contract with The Century magazine. Remington wrote Clarke on April 11, 1888: “I am going to do the ‘Black Buffaloes’—this information you will please keep private as I do not want to be anticipated.” Remington also promised Clarke in candid language that is offensive today, but all too common in the Victorian era, “All I want is one good crack at your nigger cavalrymen and d[amn] your eyes I’ll make you all famous. Do you know I think there is the biggest kind of an artist pudding lurking in the vicinity of Ft. Grant….Well write and be gracious. I have made up my mind that you are a correspondent worthy of any one’s steel.”

his Escort.

– True West Archives –

Remington made good his boast after he showed up in Arizona to take advantage of free room and perhaps board as well as libations from his host Clarke. By now the officer had received recognition not only for his derring-do in snatching Cpl. Scott from the jaws of death, but also for his other bold adventures including pursuit of the infamous Apache Kid and his band of fierce followers.

Remington admired the devil-may-care subaltern, who had been singled out for valor with a Medal of Honor for rescuing the wounded Scott. He would accompany the bold cavalier on patrol and spend time with Clarke in garrison at Fort Grant, experiences that led to the publication of “A Scout With the Buffalo Soldiers” in the April 1889 issue of The Century. The article and its accompanying illustrations, both provided by Remington, contributed considerably to the artist’s growing reputation and contained the first of his many pictorial depictions of his friend Clarke. Afterwards, Remington occasionally called upon Clarke to serve as a source, and sometimes even as a reference to verify authenticity for other sketches and paintings

– Courtesy George M. Langellier, Jr. –

While Remington’s stature developed and his body of work expanded, his comradeship remained strong with Clarke, even after each bachelor eventually walked down the aisle as the groom. The young husbands continued to correspond, in some instances sharing snippets about their travels, which in Clarke’s case included a posting to Dusseldorf, Germany, as an observer with a German mounted unit. Riding alongside these precise Prussians must have strengthened Clarke’s interest in training of the United States cavalry. After he sailed back home and reported to Fort Custer, Montana, (at the confluence of the Big Horn and Little Big Horn rivers south of present-day Hardin), he launched a determined effort to ensure the horses in his troop were capable, dependable swimmers.

With a few other officers and some enlisted men he took the steeds to swim regularly in the nearby rivers. After one of these outings he decided to take a dip himself, but he neglected to check the depth of the water. Jumping from the bank he landed in the shallows of the Little Big Horn River.

The dive proved fatal. Despite efforts to revive him, Clarke died from the fluke accident on July 21, 1893. He was 30. Thus ended what could have been an amazing martial career, robbing Clarke of further fame. In turn, Remington, who no doubt mourned the passing of his saddle “pardner” from Old Arizona, went on to become one of the most renowned artists of the frontier.

John P. Langellier, author of dozens of books and articles related to the United States Army in the West, presently is preparing a full-length biography of Lt. Powhatan Henry Clarke. He is indebted to Peter Hassrick for assistance with some of the accompanying illustrations for this True West issue.