Her $10 greenhorn mistake didn’t help.

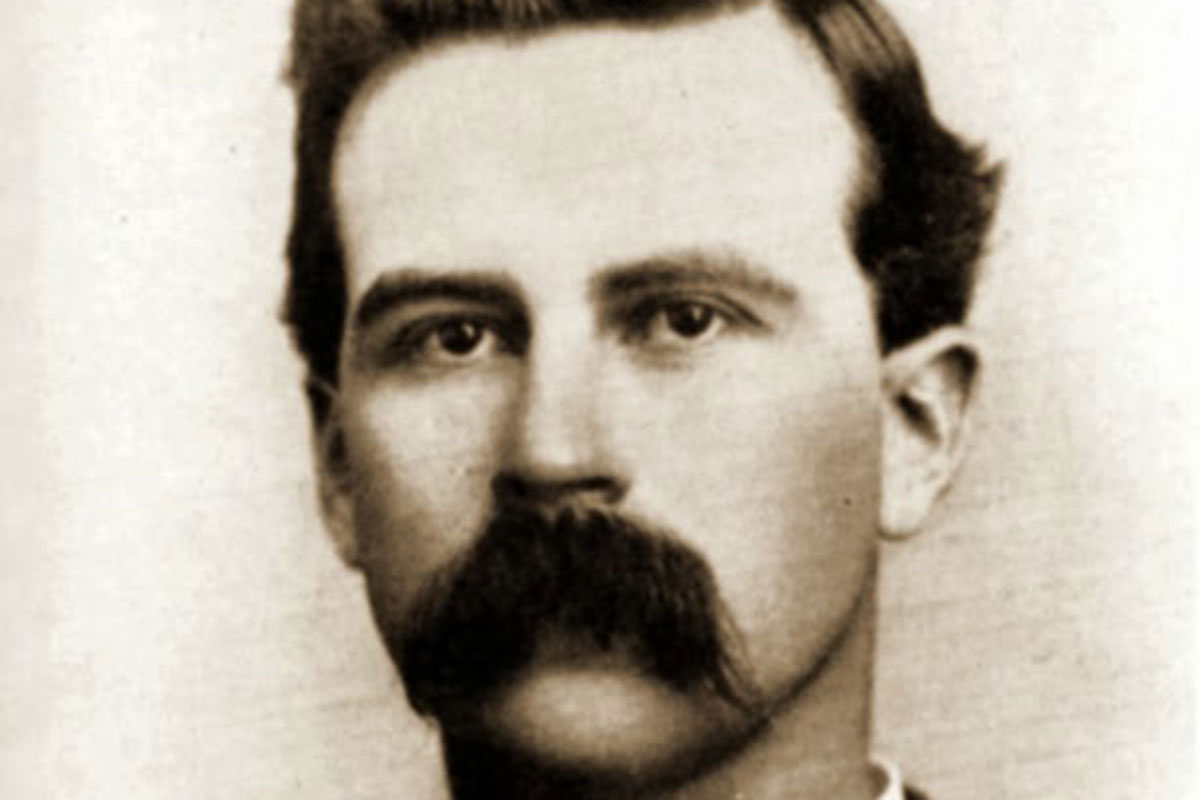

The first time Vera McGinnis entered the Big Top at Madison Square Garden in New York City, she looked like a giant Dresden doll.

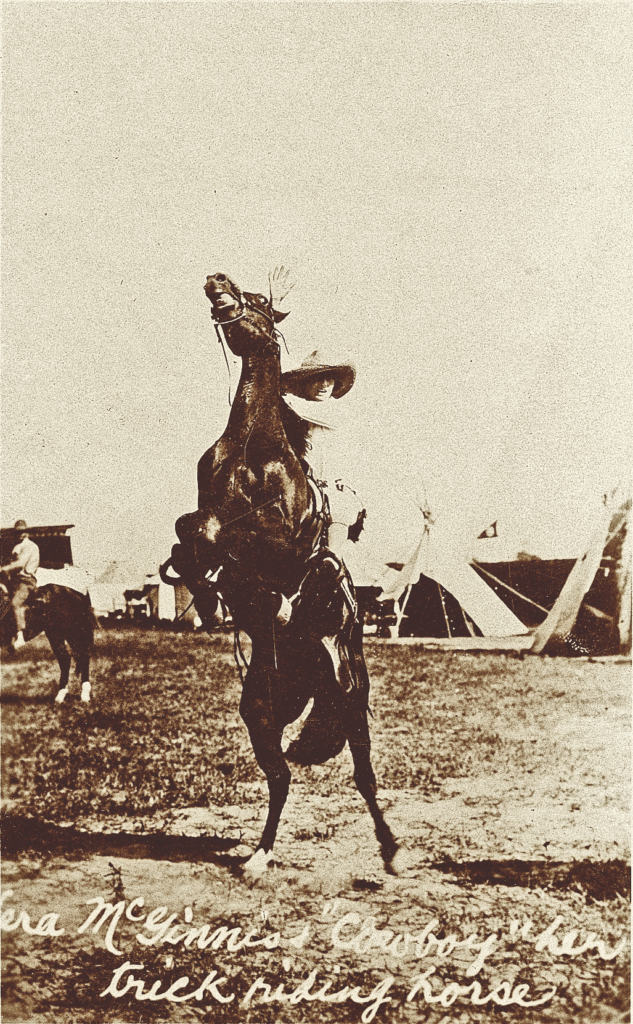

She was atop a black horse, wearing a gigantic hoopskirt that hung from her waist, its flounces reaching the ground. Her head held a giant picture hat with ostrich plumes.

“The huge backstage seemed a fairyland to me,” she’d later write. “The costumes were all crisp, new and beautiful. Everyone went in ‘Speck’—the spectacular parade that opened the show—dressed in fancy costumes. The six of us from the wild-west division had the most beautiful costumes a designer ever dreamed up—also the most uncomfortable.”

This was “The Greatest Show on Earth” and the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus paid a lot of attention to the flash and dash of showmanship.

The 1923 run at the Garden was easy and fun. There was enough space for everyone to be camped right by the big tent, and it was a cinch to do several costume changes in one day, either to show off or to perform. So Vera wasn’t prepared for how different things would be on the road.

She soon found that her Wild West dressing room, known as the “Hooligan,” was at the bottom of the pecking order. The big dressing rooms of the circus stars were, naturally, adjacent to the back door of the Big Top. Then came the “band top” for musicians and their instruments, the circus doctor’s office, the wardrobe tents and the pad room for the performing horses. After all that came space for the Hooligan, and finally, the cages for the performing animals.

Vera found all this worked fine “as long as we were pitched on a lot big enough to carry out the pattern, but when there wasn’t room for all the tents, the first to be ousted was the Hooligan. Sometimes it was blocks away.”

So Vera did a lot of walking. “We walked back and forth for horses, for wardrobe, for food, for everything—no matter how hot or miserable the weather,” she wrote in her autobiography, Rodeo Road: My Life as a Pioneer Cowgirl.

“Had I not been a ‘first of May’ (as the old circus hands called the brand-new ones), I’d never have let myself in for a lot of the work I had to do that summer,” she wrote. “My official job was to trick-ride in the concert. That meant that first I’d have to ride ‘Speck’ as everyone did, then go back into the big top for the wild-west lineup about halfway through the regular show. Then I’d be through until concert time. That is, I would have been, had I not of my own free will made different arrangements. I signed up to work with the background group for Mrs. Bradna’s ‘Act Beautiful.’ She did a bareback routine and we stood on the ring curb with baskets of pigeons we released at the end which settled on Mrs. Bradna and her pure white horse. Though it added ten dollars per week to my check, I realized it was just another greenhorn mistake.”

After displaying her Dresden doll costume, Vera had to run back and change into her Western duds, then run back again to change into the Act Beautiful costume, then dash one more time to get back into her Western outfit to perform.

“I really earned that extra ten bucks, especially through the Midwest in hot weather,” she wrote.

Vera settled into the hectic routine, but saw it as just that—a routine “without the challenge and hazards of rodeo life.” That is, until Friday the 13th of June, in South Bend, Indiana, when her friend Gordon Jones teased her into agreeing to do his Pony Express act.

“I vaulted to Gordon’s saddle and left in high, made a flying change onto the second horse and raced down the back side of the track,” she wrote. As she tried to dismount for yet a third horse, her mount shied, his head hitting her in the mouth. “I literally saw stars and hung onto the saddle horn to keep from fal-ling, one hand cupped over my mouth.” An-

other rider took over the scene, while Vera went looking for the circus doctor. He was startled as she took her hand away from her mouth. “Blood, a couple of teeth and a little horsehair were mixed up inside. He cleansed the wound and gave me a hasty examination.” Her upper jawbone was crushed, and the doctor was relieved that the next stop was Chicago, where the specialists Vera needed would help put her back together.

After months in remote parts of the country, living in a tent and bathing in a bucket, Vera had been looking forward to the excitement of Chicago, with a clean hotel room and the promise of a real hot bath.

“The ‘fun’ I had in Chicago was in a den-

tist’s chair getting bone splinters removed and submitting to all sorts of treatment.” She got a temporary plate with three teeth and kept performing, keeping her mouth shut unless one of the girls prodded her into a toothless grin. She later got a permanent bridge.

“I simply pushed the episode behind me to drag along with the inevitable physical burdens all rodeo performers have,” she wrote, nonchalantly.

When the circus closed, Vera went “straight back to Madison Square Garden—for a rodeo. It seemed nothing could cure me.”

Jana Bommersbach has earned recognition as Arizona’s Journalist of the Year and won an Emmy and two Lifetime Achievement Awards. She cowrote the Emmy-winning Outrageous Arizona and has written three true crime books, a children’s book and the historical novel Cattle Kate.