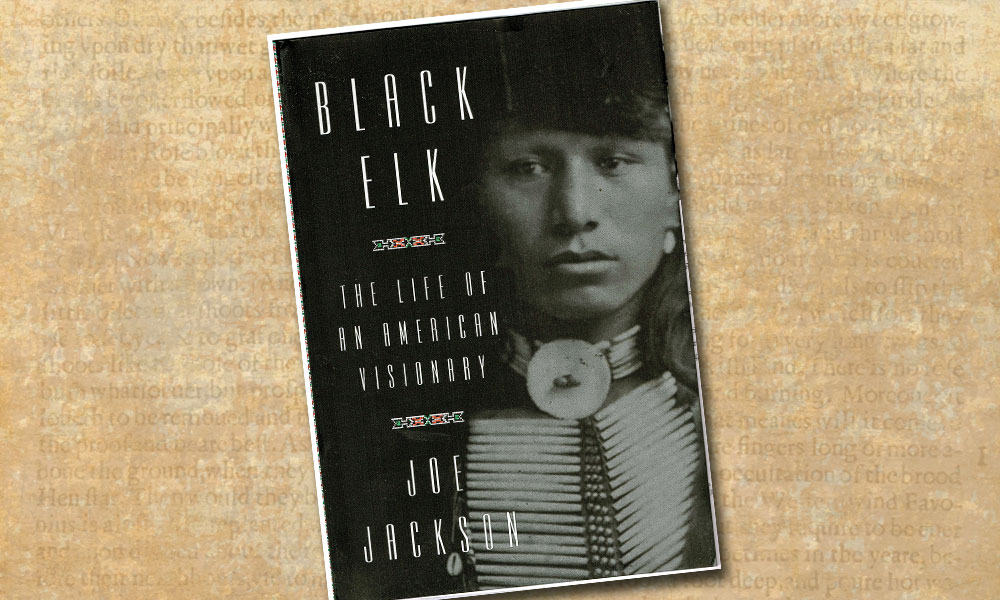

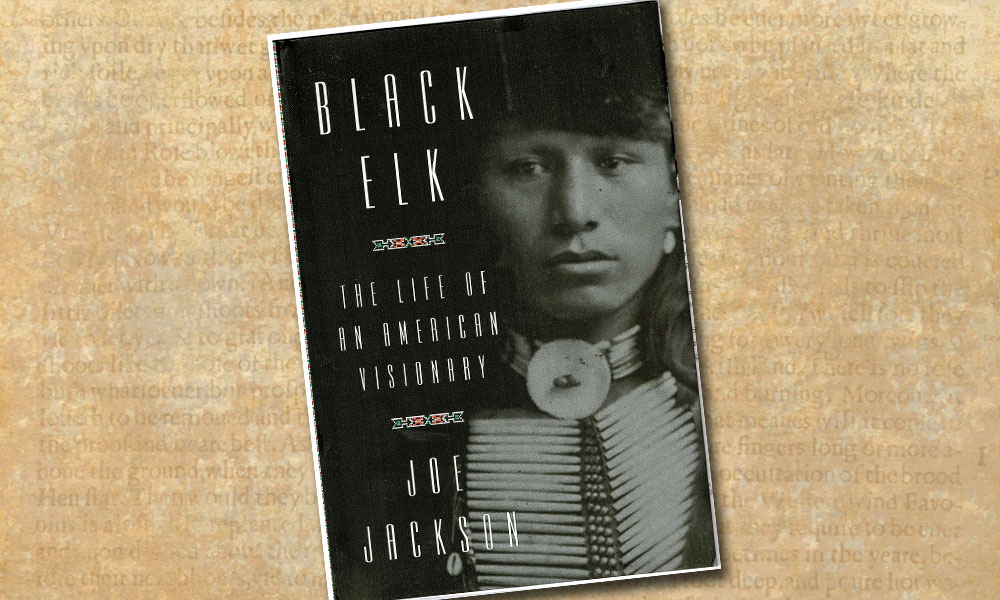

As current events in North Dakota and South Dakota swirl around pipelines, historic gravesites, life-giving waters, sacred land, natural resources, corporations versus people and courts, governments, citizenship and nationhood, Joe Jackson’s Black Elk: The Life of an American Visionary (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $30) stands as a testament to the enduring spirit of the American Indian people and their leaders, despite their cultural marginalization in United States history.

As current events in North Dakota and South Dakota swirl around pipelines, historic gravesites, life-giving waters, sacred land, natural resources, corporations versus people and courts, governments, citizenship and nationhood, Joe Jackson’s Black Elk: The Life of an American Visionary (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $30) stands as a testament to the enduring spirit of the American Indian people and their leaders, despite their cultural marginalization in United States history.

Not since Nebraska’s poet laureate John G. Neihardt published Black Elk Speaks: Being the Life Story of a Holy Man of the Oglala Sioux in 1932, has an author so expertly interpreted the life of one of the most significant Indian religious leaders in North American history.

Black Elk, who was born in the Powder River region of Montana and Wyoming, lived a life marred by conflict, on the battlefield, on the reservation and with himself. “Black Elk was a haunted man,” writes Jackson.

“The gods had given him a gift, but one he never fully understood. His search for an answer always seemed in vain.” Despite the difficulty of his personal journey, Black Elk, according to Jackson, is also one of the most spiritual American Indian leaders, a Lakota holy man converted to Catholicism who lived halfway into the 20th century, decades beyond the rural, nomadic life ways of the Great Plains tribes. As Jackson writes, “Black Elk would be what today is called a spiritual seeker—but one with a goal. … [Although] almost every decade after adulthood encompassed for him a different journey, each was an attempt to unlock his Vision and save his people—the one path he never abandoned.”

Jackson, the Mina Hohenberg Darden Endowed Professor of Creative Writing at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Virginia, has written both an eloquent and comprehensive biography of Black Elk. He has also produced a magnificent resource for researchers and readers, with a “Dramatis Personae” as a forward to the book; a detailed “Time Line;” and a 67-page “Notes” section that acts as both a bibliography and endnotes for edification of the professor’s magnanimous work, which perfectly complements Neihardt’s spiritual classic, Black Elk Speaks.

Historians and students of Western American history should consider Jackson’s biography of Black Elk a critically important addition to recent histories, including T.J. Stiles’s Pulitzer winner Custer’s Trials, Paul Andrew Hutton’s The Apache Wars, Benjamin Madley’s American Genocide and Paul L. Hedren’s Powder River. While the general populace might consider the classic story of the American Indian from the viewfinder of a 19th-century camera lens, Jackson’s story of Black Elk reminds the reader that the proverbial “end of the trail” for the American Indian did not end at Wounded Knee; rather, Black Elk, who fought at Little Big Horn, toured with Buffalo Bill, converted to Roman Catholicism and lived as a heralded Indian holy man until his death in 1950, was a human being whose life was transcendent. Black Elk’s transformational life stands today as a testament to the trials, tribulations and unceasing hope of the continent’s First Nations. Jackson’s Black Elk is an immediate classic, and should be required reading for anyone seeking a greater understanding of the importance of religious leaders in American culture—Indian or otherwise—including those watching today’s events unfolding on a daily basis in North and South Dakota along the Missouri River and the Standing Rock Reservation.

—Stuart Rosebrook