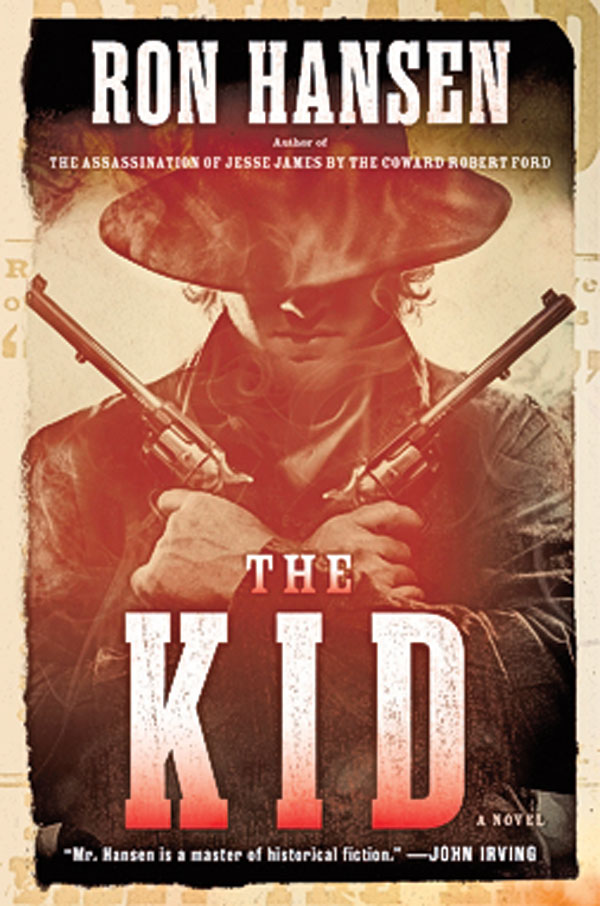

Growing up in Omaha, Ron Hansen found the Old West present in Nebraska’s cornfields, wilderness and railroad tracks full of empty boxcars. Following his U.S. Army career, he earned an M.F.A. from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in 1974, held the Wallace Stegner Creative Writing Fellowship at Stanford University and earned an M.A. in Spirituality from Santa Clara University, where he teaches writing and literature. He mixes history with morality in his novels. His first novel, 1979’s Desperadoes, reimagines the Dalton Gang. His 1983 novel, The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, landed on the short list for the PEN/Faulkner Award. His latest novel, The Kid, delves into the life of outlaw Billy the Kid. He lives in California with his wife, writer Bo Caldwell.

An early Western hero of mine was Davy Crockett, thanks to Fess Parker and his TV show.

A Jesuit education introduced me to the classics, history, philosophy, theology and other subjects that are too often neglected in public schools.

An author who influenced me at an early age is Edgar Allan Poe. His wild imagination captivated me. In high school, I discovered John Updike, a very different writer and an impeccable stylist. The first great Westerns I read were Jack Schaefer’s Shane and Walter Van Tilburg Clark’s The Ox-Bow Incident.

Serving in the Army during the early 1970s landed me at Arizona’s Fort Huachuca, which had the largest horse population of any Army post. I rode over wide-open grasslands and desert, feeling very much like a cowhand.

At the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, 30-year-old John Irving was my first teacher and mentor. Many of his writing habits became mine.

Writing Western fiction forces you to imagine far more and research more deeply just because of its foreignness. It generally asks bold questions of good and evil, right conduct and wrong, that aren’t touched on in much contemporary fiction.

My favorite course to teach is “Reading Film,” an introduction to the practicalities of moviemaking and the history of the art form that focuses on directors who are masters of the craft. This quarter, I concentrated on Stanley Kubrick.

When my novel became a Jesse James movie, I was at first suspicious of how the screenplay for The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford would look, but Andrew Dominik’s gorgeous script was completely faithful to the novel. I thought Warner Bros. would change the title to something shorter, but Brad Pitt liked my title so much, he had it written into his contract that the studio couldn’t alter it.

If I could ask Emmett Dalton anything, I would ask why he and his brothers simultaneously robbed two banks in their hometown of Coffeyville, Kansas, where everybody knew them. I guessed at the answer in Desperadoes, but the attack may have been more personal, perhaps even a vendetta.

Billy the Kid’s life shows how important a father’s influence can be on teenage boys. Orphaned at 14 and cruelly ignored by his stepfather, he hero-worshipped men a little older than him who themselves were killed off right in front of the Kid.

The biggest problem in writing fictional history is people think they already know the story, when it’s often a botched version of someone’s life. They are generally pleasantly surprised by the facts.

My favorite Billy the Kid movie is One-Eyed Jacks, based on Charles Neider’s The Authentic Death of Hendry Jones. Marlon Brando and Karl Malden are versions of the Kid and Pat Garrett, and the acting and dialogue are terrific.

The secret to capturing the Kid’s life is a form of method acting. I found situations comparable to the historical ones I wrote about and recalled how I had handled them. A lot of myself is in any character I imagine, but I felt a kinship to Billy.