When I wrote that paragraph as the conclusion of my June 1990 New Mexico Magazine article, I thought I was finished with Billy the Kid.

Little did I know that those words would take me to Hollywood to help promote Young Guns II, to several spots as a talking head on Billy with the Discovery, Disney, BBC and History Channels,?to a stint as Gov. Bill Richardson’s historian on the project to disprove the Brushy Bill Roberts tall tale, to a job as a writer/producer on a Billy program and several others with Bill Kurtis on the Investigating History series on the History Channel and to enduring friendships with several other Billy addicts, including the executive editor of this magazine, Bob Boze Bell.

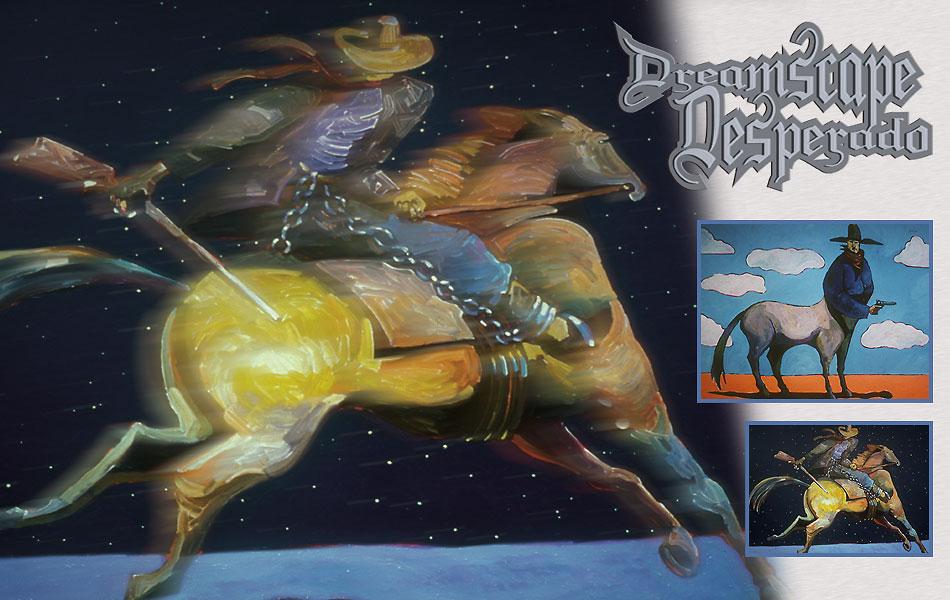

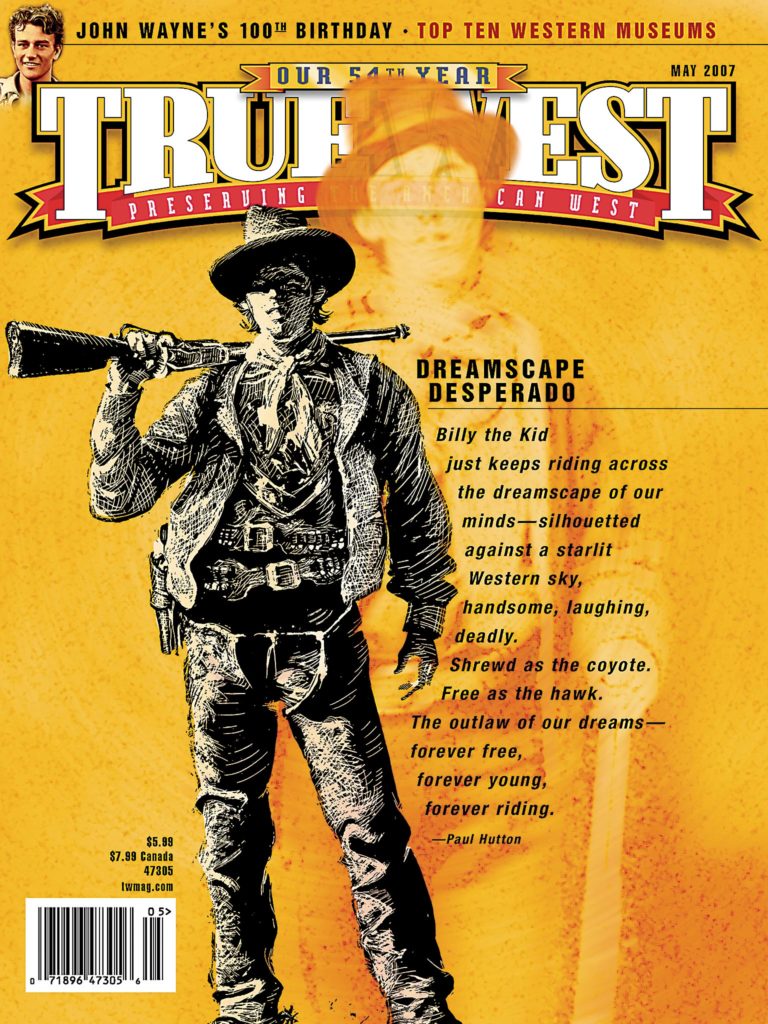

My latest Billy endeavor is as guest curator of “Dreamscape Desperado: Billy the Kid and the Outlaw in America” at the Albuquerque Museum of Art and History. The exhibit will illuminate the Billy of reality as well as the Billy of myth. The story will be told through a wide range of artifacts (many from the fabulous Robert G. McCubbin Collection) and visually interpreted through the artwork of Bob Boze Bell, Thom Ross, Buckeye Blake, Maurice Turetsky and Peter Aschwanden. The University of Oklahoma Press will be publishing a companion volume to the exhibit.

May 13-July 22 in Albuquerque, New Mexico albuquerquemuseum.com • 505-243-7255

Who remembers Billy the Kid?” Harvey Fergusson asked in the June 1925 issue of H.L. Mencken’s The American Mercury. Fergusson, a talented Southwestern novelist best remembered for his 1937 bestseller The Life of Riley (the inspiration for the William Bendix radio and TV comedy), had fallen under Billy’s spell as a boy.

“A melodrama, portraying Billy as a promising youth ruined by evil companions, was written and put on the boards; I saw it in the West as late as 1913,” he waxed nostalgic. “An enterprising fellow, whose name I forget, made a living for years by exhibiting a skeleton, alleged to be that of the bandit, at ten cents a look. Hundreds of thousands paid their dimes to gape at it.”

Fergusson, a hopeless romantic, saw Billy as “the key figure of an epoch—the primitive pastoral in the history of the West.” The outlaw youth was not only typical of the era to Fergusson, but also a perfect hero somehow overlooked by history. This puzzled the novelist, for he felt certain that “Billy had in a high degree all the qualities which impress the imaginations of simple men.”

What stirred Fergusson’s imagination, and countless Billy admirers since, was that the Kid was no crass criminal like Jesse James who was in it only for the money. “Billy was a quixotic romantic, who cared nothing for money,” stated Fergusson. “He lived and died an idealist.”

A Tragic Hero

Chicago newspaperman Walter Noble Burns must have read Fergusson’s article with considerable interest. His 1926 book, The Saga of Billy the Kid, follows Fergusson perfectly in terms of thematic content. Burns, a talented popular historian who had great success with his books on Wyatt Earp and Joaquin Murietta, brilliantly captured the mythical power of the Kid’s story in his book, setting the tone for Billy the Kid literature for half a century to follow. The biography, a main selection of the new book-of-the-month club, became a runaway bestseller.

“A Robin Hood of the Mesas, a Don Juan of New Mexico, a cowboy outlaw whose youthful daring has never been equaled in our entire frontier history” read the breathless dust jacket copy. The book struck a responsive cord across the nation. The outlawed youth, fighting for justice in a world of swirling corruption, is eventually betrayed by his friend Garrett and killed. The tale fired up the imaginations of readers everywhere and Billy, so long forgotten, was back with a vengeance.

MGM quickly optioned the book with King Vidor directing the big-screen adaptation. It starred football star Johnny Mack Brown as Billy with Wallace Beery as Pat Garrett. The pesky problem of Garrett’s betrayal of the Kid was solved by having the affable sheriff let the charming boy escape with his blushing bride at the end. It was hardly the last time Billy would ride off into a celluloid sunset. Only Europeans, evidentially better able to handle tragedy than American audiences, got to see Billy die at the end of Vidor’s film.

The Saga of Billy the Kid and the Vidor adaptation of it elevated the forgotten outlaw to a central place in the pantheon of American heroes. The Kid never looked back. While previous books by Charlie Siringo and Emerson Hough had helped keep the Kid’s legend alive, it was Burns’ book that created an enduring American—even international—myth. Burns, building on the themes suggested by Fergusson, fully realized the epic potential of the story and the romantic possibilities of the Kid as a tragic hero.

Leaping Fifths

Lincoln Kirstein, founder of the Ballet Caravan in 1933, read Burns’ book and gave a copy to his friend, choreographer Eugene Loring, suggesting the possibility of the tale as a ballet. Loring agreed, and the two men set out to find a composer. Kirstein met Aaron Copland—a Brooklyn-born Jewish composer beginning to create a distinctive American style in Classical music—at a New York salon owned by Kirk and Constance Askew. Composer Virgil Thomson, poet E.E. Cummings, choreographer Agnes de Mille and artist Salvador Dalí were among the regulars at the East 67th Street brownstone. In this unlikely setting, the deal was struck for one of the most distinctive works of musical Americana. Kirstein even gave Copland collections of cowboy songs—Songs of the Open Range and The Lonesome Cowboy—in hopes of inspiring him to use these folk melodies in his composition.

Copland humored Kirstein and took the recordings with him to Paris in the summer of 1938. Hispanic tunes appealed to him far more than what he termed “poverty stricken” cowboy songs. But the heroic story of Billy the Kid and the Western music that celebrated it captivated Copland. “It wasn’t very long before I found myself hopelessly involved in expanding, contracting, rearranging and superimposing cowboy tunes on the Rue de Rennes in Paris,” he later recalled.

He made use of six Western tunes to create his score for the one-act, seven-movement ballet. Five of those were used in Billy the Kid’s most ambitious scene, “Street in a Frontier Town”—a composition that has influenced Western film music composers ever since.

Billy the Kid opened at Chicago’s Civic Opera House on October 16, 1938, with Eugene Loring as Billy and Richard Reed as Garrett before moving on to New York in May 1939. It became an instant classic. After Billy dies at the end, the brass band played chords of leaping fifths, likely indicating that the composer wanted his audience to feel sympathy for the Kid. Copland later revised his score into a 20-minute suite for orchestras that also enjoyed wide acclaim, remaining a popular recording to this day.

Celluloid Billy

While the highbrows studied the nuances of the ballet, the less sophisticated followed the race between MGM and Howard Hughes to get two competing Billy the Kid films into America’s theaters first.

MGM’s glossy remake of the King Vidor epic, starring Robert Taylor, won the race because Hughes’ film deeply offended the Hays production code office with its attempt to exploit the amazing anatomical attributes of starlet Jane Russell to their maximum potential. Hughes’ The Outlaw, starring Russell, Walter Huston (as Doc Holliday), Thomas Mitchell (as Garrett), and Jack Beutel (as Billy), remains one of the most bizarre Western films ever made.

The censorship battle—centering on the fact that Billy in the film is not killed as punishment for his crimes (as he was in the MGM film) and on the heterosexual and homosexual themes—delayed The Outlaw’s release until a limited run in 1943 and the general release in 1946.

The subject of Billy the Kid seems to invite such cinematic excess. Other movies on the same controversial plane as The Outlaw include Dennis Hopper’s 1971 The Last Movie (the actor playing the Kid in this film-within-a-film gets killed), Marlon Brando’s 1961 One-Eyed Jacks (the Kid’s life was grafted into a tale of vengeance) and E. Kutlug Ataman’s 1999 Lola and Billy the Kid (a Turkish-language film about the romance between a teenage boy and a Berlin transvestite).

Thank publicist Russell Birdwell (promoter for Gone with the Wind and John Wayne’s The Alamo), and not Hughes, for cutting through the controversy surrounding The Outlaw by exploiting Russell’s sensual potential. Photos of a pouting Russell reclining in a haystack with a pistol in her hand, accompanied by slogans such as “Mean, moody, and magnificent” and “Two good reasons for seeing The Outlaw,” blanketed the country. Hughes, who had fired director Howard Hawks and taken control of the production, had a hit on his hands. Despite the mocking reviews and censorship battles, people flocked to the film. Billy the Kid was more famous than ever, but it was sex, not history, that sold his story.

One casualty of Hughes’ battle with the censors was the B-western “Billy the Kid” series. Roy Rogers had just starred as a cowboy, mistaken for the recently deceased Billy, who cleans up Lincoln County with a guitar and six-gun in Republic’s successful 1938 film. The responsive public encouraged Producers Releasing Corporation (PRC) to begin a series of films about the outlaw youth. Producer Sigmund Neufeld and his brother, director Sam Neufeld (usually credited as Sam Newfield), made 19 Billy the Kid Westerns between 1940-43. Bob Steele first starred as Billy, aided by sidekick Al “Fuzzy” St. John, in six films before heading to greener pastures at Republic Studios. Buster Crabbe, of Flash Gordon fame, replaced Steele for the rest of the series.

In 1943, the main character’s name was changed to Billy Carson when censorship groups objected to the glorification of an outlaw in films for children (responding to the negative publicity fallout from The Outlaw). Crabbe would star in 23 more Billy films, but not as Billy. Each film, even though they had nothing to do with the real Billy, further enhanced the Kid’s image as an American hero.

Cinematic Excess

By 2007, 60 films about Billy have been made—making him the most filmed historic figure in America.

The demise of the PRC series hardly dented the flood of Billy the Kid films. Audiences sat enraptured before the flickering images of Lash LaRue as Pat Garrett’s son in Son of Billy the Kid (1949), Joel McCrea as the renamed Kid character in Four Faces West (1948), America’s most decorated war hero Audie Murphy as The Kid from Texas (1949), B-Western star Don “Red” Barry as Billy in I Shot Billy the Kid (1950), stalwart Scott Brady in The Law vs. Billy the Kid (1954) and brooding Nick Adams in Strange Lady in Town (1955).

Every story angle was exploited. Billy (Anthony Dexter) battled for the Lord in The Parson and the Outlaw (1957). He was the impetus for slapstick comedy (Johnny Ginger) in the Three Stooges farce The Outlaws is Coming (1965). He fought forces of darkness in both Billy the Kid versus Dracula (1966) and Billy the Kid and the Green Baize Vampire (1985). He even helped out on a homework assignment of two righteous dudes in Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure (1989).

Television embraced Billy as an all-American boy. He had his own series on NBC, The Tall Man, with Barry Sullivan as Garrett and Clu Gulager as Billy. It only ran two seasons, but the Kid’s media exposure was hardly daunted by its cancellation. Billy was everywhere on the small screen: played by Paul Newman in an early Philco Television Playhouse; Joel Grey on Maverick; Robert Blake on Death Valley Days; Ray Strickland on Cheyenne; Stephen Joyce on Bronco; Andrew Prine on The Great Adventure (Prine later plays lawyer McSween in Chisum); Robert Conrad on Colt.45; Robert Vaughn on Tales of Wells Fargo; Dennis Hopper on Sugarfoot; and Robert Walker, Jr., on Time Tunnel. Richard Jaeckel must set a record for his cinematic link to Billy—playing Billy in Stories of the Century and 1978’s TV movie Go West, Young Girl, and playing Jesse Evans in Chisum and Kip McKinney in Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid.

Television movies also celebrated the Kid: Gore Vidal’s Billy the Kid in 1989, with Val Kilmer as a deeply disturbed Billy, and Purgatory in 1999, with Donnie Wahlberg as a ghostly Kid. As the cable industry expanded in the 1990s, Billy the Kid turned up quite often in pro-gramming such as A&E’s Real West and the History Channel’s Investigating History (the Billy episode was written by me and producer Bill Kurtis). For half a century, Billy has remained a TV regular.

By the mid-20th century, Billy the Kid had also entered the American vernacular as a synonym for a rebel. Sports stars with an edge (think Billy Martin) were repeatedly referred to as Billy the Kid, as were singers, politicians and just about anyone who defied the establishment or displayed hot-headed, youthful enthusiasm.

Billy proved to be an adaptable, resilient hero, which gave him an amazing longevity. His rebel ways attracted Hollywood writers and producers to Billy in a way denied more traditional frontier heroes (Custer, Kit Carson, Buffalo Bill) as attitudes toward the conquest of the West changed. In the late 1950s, he was the perfect rebellious teenager as portrayed by Paul Newman in Arthur Penn’s The Left Handed Gun (1957). Of course, we know the Kid was not left-handed—the confusion arose from the famous reversed tintype photo—but to Hollywood, he should have been.

While it seemed impossible to outbrood Newman’s Billy, that task was easily accomplished by Marlon Brando in 1961’s One-Eyed Jacks. After Producer Frank Rosenberg read Charles Neider’s excellent novel based on Billy the Kid, The Authentic Death of Hendry Jones, he bought the rights for $25,000 in the summer of 1957. He then hired TV writer Sam Peckinpah to adapt it into a screenplay for scale—then $3,000. Rosenberg sent the screenplay to Marlon Brando, Hollywood’s consistent rebel, who was searching for a Western for his next picture. Although others thought Peckinpah’s script needed considerable work, Brando loved it and Paramount put One-Eyed Jacks on the fast track.

Brando and director Stanley Kubrick went off for six weeks to rewrite the script. Calder Willingham, who had worked with Kubrick on the classic WWI film Paths of Glory, was then brought aboard to rewrite the rewrite, and on it went for months. Kubrick was fired when Brando suddenly decided to direct the film. “This guy is a fake,” he declared of Kubrick. By the time the company arrived in Monterey, California, to begin filming in December 1959, the movie already had a marvelous pedigree of cast-off talent but still no ending. It would end up a train wreck of epic proportions.

The set was just as troubled as had been pre-production. The 60-day schedule expanded to six months thanks to Brando’s directing style. “He pondered each camera set-up while 120 members of the company sprawled on the ground like battle-weary troops,” recalled producer Rosenberg. “He exposed a million feet of film, thereby hanging up a new world’s record.” Brando’s cut of One-Eyed Jacks ran four hours and 42 minutes, going four million dollars over budget. When finally released in March 1961, after Paramount forced Brando to film a new, happier ending in which the Kid rides into a California sunset, the film failed miserably at the box office. Brando publicly disowned it.

Too bad, since Neider’s original revenge tale of the Rio Kid (Brando) and the outlaw pal (Karl Malden) who betrays him and then becomes a sheriff had enormous potential. The final film, which also featured Ben Johnson, Slim Pickens (as the Olinger character) and Katy Jurado, had flashes of brilliance with beautiful photography by Charles Lang and a lush musical score by Hugo Friedhofer. It is reflective of the kind of talent consistently attracted to the Kid’s compelling story, and the enormous difficulty in getting the story right.

The West’s Everyman

If Billy was a tragic and tormented rebel in the late 1950s, he was Everyman by the 1970s. In four dramatically different films, the Kid reflected the divisions then tearing at the fabric of American society.

Billy opened the decade in a big budget, traditional John Wayne Oater, Chisum (1970), directed by Andrew V. McLaglen. Andrew Fenady’s exciting script turned history upside down, as Wayne’s Chisum, the ultimate benevolent capitalist, wiped out the bad guys led by Forrest Tucker in the Lincoln County War with the help of his reckless ally Billy, played by Geoffrey Deuel. All is peaceful at film’s end, although the Duke frets a bit over Billy’s marked tendency toward violent behavior.

In 1971, Universal released Dennis Hopper’s The Last Movie, a truly bizarre take on the razor-thin line between art and reality. The last movie in this film-within-a-film is, of course, about Billy the Kid with Sam Fuller playing himself as the crazed director pushing for realistic perform-ances from actors Dean Stockwell as Billy and Rod Cameron as Garrett. Shooting on location in Peru, the movie took an unexpected turn when the local villagers take on the story as their new reality. Along for this madcap ride were Hopper’s pals Kris Kristofferson and Peter Fonda. The film, which makes no sense whatsoever, won first prize at the Venice Film Festival and then vanished.

The next year, Stan Dragoti’s Dirty Little Billy debunked the Kid’s heroic image just as other films of that increasingly cynical period attacked Jesse James, Wyatt Earp and Gen. George Custer. Michael J. Pollard’s Billy—lazy, degenerate and cowardly—lives in a world of filth and corruption. He fits right in. But Pollard’s depiction of Billy as a sniveling punk held no appeal to the youthful audiences of 1972, with the film failing miserably at the box office.

Far more attuned to the times was Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid, released the same year. Kris Kristofferson played Billy as a charming anarchist and violent anachronism with no place in the corrupt new order that is coming to power in the West. James Coburn’s Pat Garrett must abandon obsolete conceptions of loyalty and sell out his old friend Billy in order to win a place in that new order. But Garrett’s law, arbitrary and illegitimate, exists only to protect the rich and politically connected. The film plays as a ballet of death between the two protagonists. Garrett finally realizes that by killing Billy, he has committed spiritual suicide. As he rides out of Fort Sumner, a young boy, in a parody of the ending of Shane, follows, throwing stones. The film remains a flawed but powerful masterpiece—perhaps the best of all the Kid movies.

Peckinpah’s film was one of the last successful Westerns before the genre vanished from movie screens for nearly 15 years. Then 20th Century Fox’s “Brat Pack” hit Young Guns gave a new lease on life to the dormant genre in summer 1988. The movie seemed to some an effort to transplant the Los Angeles Crips into 19th-century New Mexico, but its serious tone, authentic look, quick violence and personable young stars won over audiences.

Although truer to history than previous films, John Fusco’s script has his young guns nevertheless win their generation-gap range war, killing the chief villains in a finish as wildly inaccurate as the one in Fenady’s Chisum. The success of the film prompted Fusco to pen a sequel that also took liberty with some facts. Teen heartthrob Emilio Estevez recapped his truly inspired performance as Billy in a tale that piled up corpses and box office receipts at an equally astonishing rate. Young Guns II strongly suggested that the Kid escaped Garrett’s ambush to live on under the alias of Brushy Bill Roberts. In 1990, Fusco had just as difficult a time killing off his hero as King Vidor had back in 1930. But after all, this is Hollywood and not a history lesson.

Hollywood has found Billy the Kid to be a delightfully pliable subject. From Robin Hood to tormented adolescent, from quiet avenger to degenerate punk, and from martyred symbol of freedom to hip gang leader, he has been continually manipulated to satisfy new audiences. Each generation of filmmakers has reinterpreted this familiar story to fit a new vision, one shaped by the peculiar social milieu of a changing America.

Billy Literature

The literary set also took hold of the Kid. Billy may not have been a major figure in the dime novels of the 19th century, but he became a mainstay of postwar comic books. America’s Toby Press debuted a “Billy the Kid” comic book series in 1950 that ran for five years. Charlton Comics followed in 1957 with a series that ran for 145 issues, becoming the last of the major Western comic series when it ceased publication in 1983.

In Britain, Billy was featured regularly in the Sun from 1953-61 as well as in boys’ hardback annuals. He was also a favorite of French and Italian comic book artists, although books by them were aimed at a mostly adult audience.

Adults back in the states could get a steady diet of Billy’s adventures in the pulps, Western fiction rags and Western history magazines published from the 1930s to the end of the century. (Billy obviously remains a popular topic in the only survivors of this magazine trio—the popular Western history magazine.)

Today, you’ll find Billy stories published in mass market Westerns by authors such as Zane Grey, Dane Coolidge, Nelson Nye, Johnny Boggs and Matt Braun. Some Kid novels have even become minor classics, most notably Edwin Corle’s Billy the Kid (1953), Charles Neider’s The Authentic Death of Hendry Jones (1956), upon which One-Eyed Jacks was based, Michael Ondaatje’s Collected Works of Billy the Kid (1970), the source of Oakley Hall’s play, “Apaches” (1986) and Loren Estleman’s Journey of the Dead (1998).

Great anticipation preceded the release of Larry McMurtry’s Anything for Billy in 1988, his first Western since winning the Pulitzer Prize for Lonesome Dove. Although the book lingered over four months on The New York Times bestseller list, many readers were disappointed for McMurtry’s farcical tale bore little resemblance to Lonesome Dove. The author had no use for Billy, who he depicts as tiny in stature, ugly to behold, constantly filthy, doltish and always murderous, with a conscience like a “blank domino.” McMurtry softened this dark image a bit in his recent novel, Telegraph Days, in which Billy has a cameo.

N. Scott Momaday presented a lyrical, softly romantic vision of the Kid in The Ancient Child. Momaday’s novel, his first since winning the Pulitzer Prize for House Made of Dawn, was also eagerly awaited. His Billy is handsome, daring, articulate, always ready to laugh—truth seen through a poet’s eye. “It has something to do with legend,” Momaday writes, “and with the way we must think of ourselves, we cowboys and Indians, we roughriders of the world. We are lovers of violence, aren’t we?”

Historian Robert Utley was amazed at the magnetic pull the outlaw youth held over the public’s imagination. His 1987 scholarly High Noon in Lincoln had received little media attention and only modest sales, but his 1989 Billy the Kid became a History Book Club selection, receiving enthusiastic reviews in many papers and even a brief notice in The New York Times. Foreign editions and royalties piled up, leaving Utley pleased but bemused. “My excursion into New Mexico outlawry ended in caustic irony,” he later wrote. “High Noon in Lincoln the book I thought would find a large and appreciative readership, the book in which I invested three years of research and writing, achieved only modest success. Billy the Kid, tossed off in eight months, soared to sales and accolades beyond anything I had ever written.”

Other academes shared in Utley’s frustration, as their own work went unnoticed while the Kid, just as he had challenged the establishment a hundred years before, mocked them by his hold on the public’s imagination. They took their potshots—pointing out how works on race, class and gender in the West were being ignored—but they couldn’t sway the public from latching on to Billy.

Digging Up Billy

With Billy the Kid flourishing so much in popular culture mediums, it shouldn’t be surprising that he would end up the focus of a real-life drama.

Three New Mexico lawmen, sick of Pat Garrett’s good name being dragged through the dirt due to allegations that he may have freed the Kid instead of killing him at Fort Sumner in 1881—initiated an investigation into the Kid’s death and burial in spring 2003. Sheriff Tom Sullivan of Lincoln County and his Deputy Sheriff Steve Sederwall, along with DeBaca County Sheriff Gary Graves were determined to prove that Brushy Bill Roberts of Hico, Texas, was not Billy the Kid. (The Lincoln County Heritage Trust may have thought that its 1989 committee had put a stake through the heart of the Brushy Bill story, but like Dracula in Billy the Kid versus Dracula, Brushy Bill just kept rising from the grave.)

New Mexico’s high-profile Gov. Bill Richardson lent his support to the lawmen in their effort to protect New Mexico’s most famous citizen from this Texas imposter. “This is not a publicity stunt; it’s an effort to get at the truth,” Richardson told a room packed with reporters on June 10, 2003. He was flanked by the Stetson-bedecked sheriffs of Lincoln and DeBaca Counties, and by me, appointed as historian on the project. The governor and the sheriffs proposed to dig up Billy’s mother in Silver City and compare her DNA with that of the imposter Roberts.

The story made headlines from New York (including a front page story in The New York Times) to Bombay. CNN interviewed the governor about Billy while the BBC, Discovery and History Channels filmed programs on the controversy. True West magazine’s highest-selling copy of 2003 was its August/September issue, with the cover story “Digging Up Billy the Kid.”

Irate officials in Silver City and Fort Sumner quickly announced that they would fight any exhumations. Billy the Kid scholars Fred Nolan and Bob Utley joined in, along with political columnist Jay Miller, to denounce the project.

The governor, no amateur at this game, gingerly sidestepped his critics by moving the debate to a pardon for Billy (once promised but never delivered by Gov. Lew Wallace, see p. 64). A force to be reckoned with, like Billy had been, Gov. Richardson made clear that much of his intent in supporting the investigation was to call attention to the colorful history of New Mexico, which the Kid still perfectly represented.

The myopia of those opposed to the project is astonishing but predictable. Billy the Kid seems to invite controversy no matter the issue at hand. Governor Richardson, although busy running his state—negotiating with the North Koreans and Sudanese, and attempting to save the national Democratic Party from implosion—still remains hot on the trail of Billy the Kid; it remains unclear if that road will lead to a pardon.

Who Remembers BTK?

The answer is, of course, just about everyone. More than 125 years after his death, it is impossible to forget him: Every boy wants to be him, and every girl wants to be with him. He is our own deadly version of Peter Pan morphed into Robin Hood. The eternal boy who refuses to grow up, change or compromise or sell out, and—most important—sees injustice through innocent, youthful eyes and does not hesitate to set it right.

What would Billy do? As we adults face our own difficult and complex world of corruption and compromise, it is somehow comforting to think of the outlaw youth with his crystal-clear vision of gunsmoke justice. We were all once “The Kid.” That is why he remains the outlaw of our dreams.

Photo Gallery

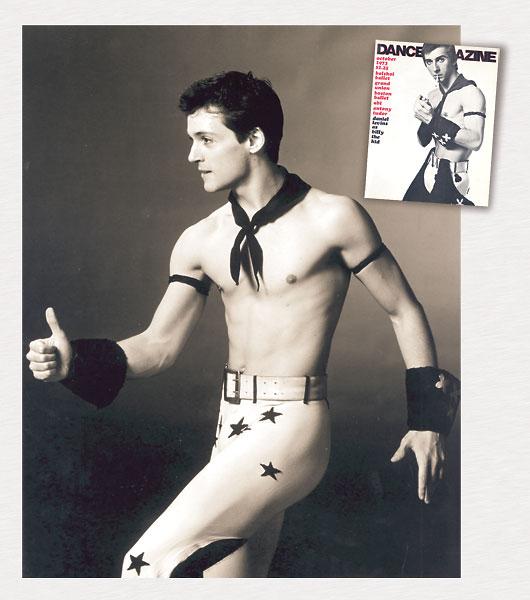

Angel Corella was Billy during the Spring 1999 season at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York. Daniel Levins’ Billy was the cover story of the October 1973 Dance Magazine.

Billy the Kid just keeps riding across the dreamscape of our minds—silhouetted against a starlit Western sky, handsome, laughing, deadly. Shrewd as the coyote. Free as the hawk. The outlaw of our dreams—forever free, forever young, forever riding.

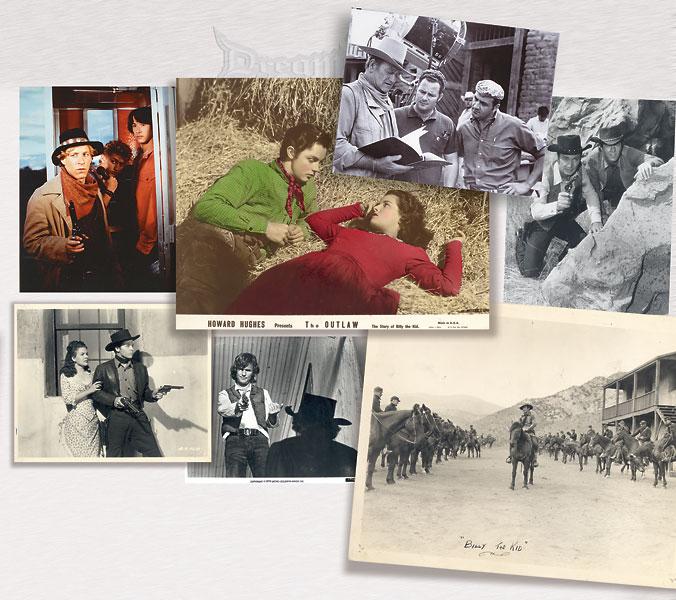

(Clockwise, from top left) Poster art for the 1989 Turner production of Gore Vidal’s Billy the Kid starring Val Kilmer; the Regulators ride into Lincoln in John Fusco’s 1988 hit film Young Guns; an ad for Stan Dragoti’s 1972 Dirty Little Billy; a poster for the 1938 Roy Rogers feature Billy the Kid Returns; an ad for Dennis Hopper’s eccentric The Last Movie; an advertising card for the turn-of-the-20th-century play that so inspired young Harvey Fergusson; British sheet music for the lush love theme by Hugo Friedhofer for One-Eyed Jacks.

(Clockwise, from top left) Dan Shor as Billy helps out Alex Winter and Keanu Reeves in Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure (Orion, 1989); Billy (Jack Beutel) contemplates his next move with Rio (Jane Russell) in The Outlaw (United Artists, 1943); John Wayne, Michael Wayne and screenwriter Andrew Fenady on the set of Chisum (Warner Brothers, 1970); Barry Sullivan and Clu Gulager star as Garrett and Billy in the 1960-62 NBC series The Tall Man,/i>; Johnny Mack Brown rides into Lincoln to meet with Gov. Wallace in Billy the Kid (MGM, 1930); Kris Kristofferson’s Billy breaks out of the Lincoln jail in Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (MGM, 1973); Gale Storm and Audie Murphy in The Kid from Texas (Universal, 1950).

This 1958 Canadian midget wrestling program celebrates Billy as a straight shooter. You can’t make up this stuff.

(Clockwise from top, left) A British Billy in Cowboy Picture Library (Fleetway, 1961); a comic book adaptation of the film The Left Handed Gun (Dell, 1958); an Italian Billy comic book from the series “Storia del West” (Daim, 1990); Billy the Kid’s Old Timey Oddities by Eric Powell and Kyle Hotz was the first of four issues (Dark Horse Comics, 2004); the One-Eyed Jacks movie tie-in edition of Charles Neider’s The Authentic Death of Hendry Jones (Fawcett, 1960); Robert Marshall’s Billy the Kid on Tall Butte (Saalfield, 1939) was part of the “Big Little Book” series for kids; the paperback version of Larry McMurtry’s Anything for Billy (Pocket Books, 1988); Arda LaCroix’s pulp novel Billy the Kid was based on the Joseph Santley/Walter Woods play (Ogilvie, 1907); Billy the Kid was serialized in the British Sun weekly comics from 1953-61; a teenage-punk cover graces the paperback version of Edwin Corle’s Billy the Kid (Bantam, 1953); (Center) Leon Morgan’s Billy the Kid (Whitman, 1935) was an early juvenile book.