It’s been called the Haywood Trial, after one of the defendants. Others have named it the Steunenberg Case in reference to the victim. Media trumpeted it as the “Trial of the Century.” Without a doubt, it is one of the most fascinating events in Old West history.

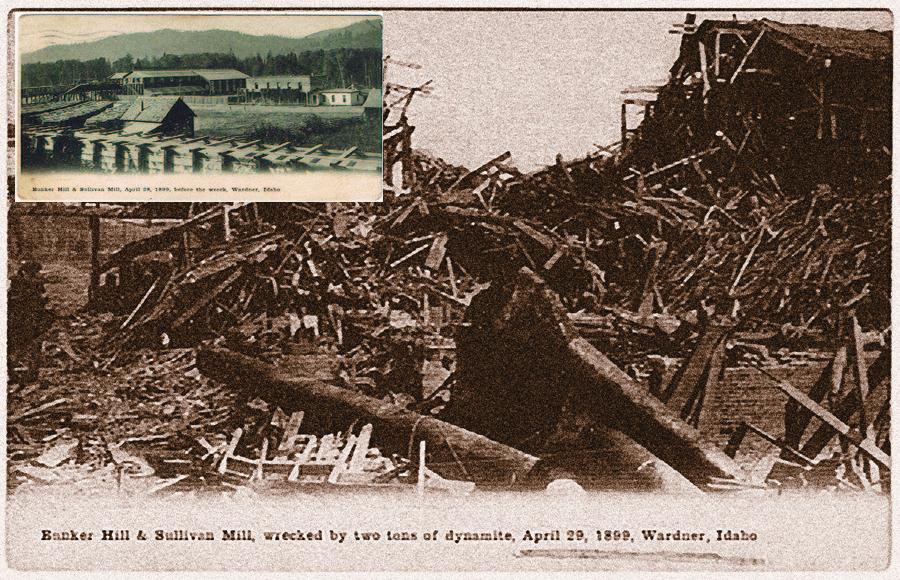

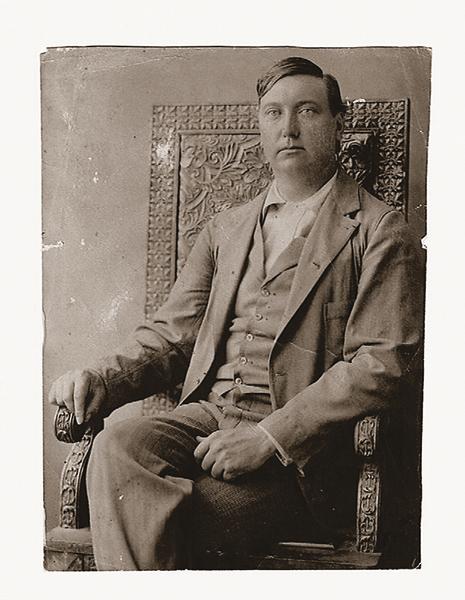

It all started nearly a decade before. In April 1899, members of the Western Federation of Miners (WFM) went on strike against mine operations in the Coeur D’Alene region of northern Idaho. The situation turned violent with skirmishes between the two sides. Governor Frank Steunenberg, who’d been elected in a landslide in 1896, was forced to take action. State National Guard troops were all serving in the Philippines in the wake of the Spanish-American War, so the governor requested help from Washington. President William McKinley sent in black army units—the famed Buffalo Soldiers—to reestablish law and order. That was not a popular decision with the pretty much all-white WFM strikers.

The soldiers took more than 1,000 men into custody, holding them in “bullpens” in an old barn and several boxcars. Conditions were terrible; sanitation was poor, food was meager and the blazing summer heat took a toll. At least three prisoners died, and several others became ill. When a handful of men attempted to escape, the entire group was put on bread and water rations for more than a week. A newspaper editor who criticized the situation was himself tossed in the bullpen. Most of the detainees were held for nearly five months before being released.

Needless to say, the miners were angry and bitter over their treatment. Governor Steunenberg received countless death threats; he and his family needed special security details to protect them in public.

He caved to the pressure and decided not to run for re-election. Instead, at the start of 1901, he went back home to Caldwell, a small town about 30 miles east of Boise, where he and his brothers were involved in banking, retail, publishing, mining and other business ventures. Steunenberg was still a relatively young man at the age of 39; the best years of his life seemed to be ahead of him. And as time went on, the threats against him were pretty much forgotten.

Except by some union members.

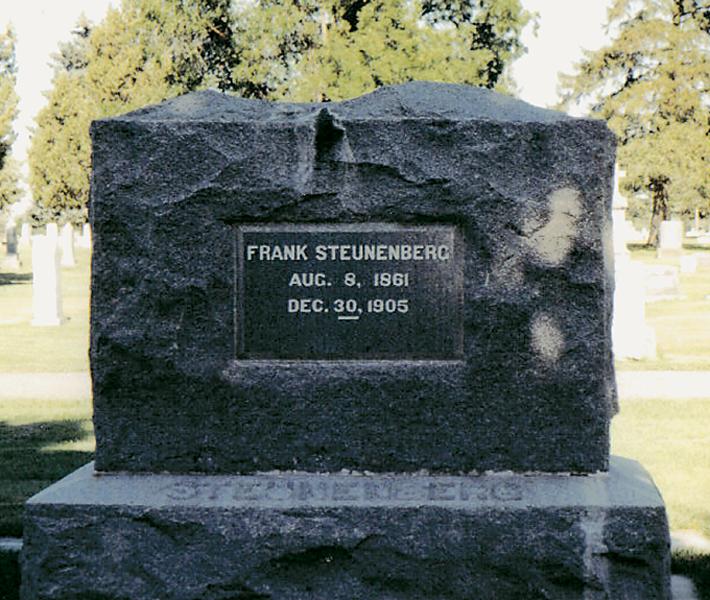

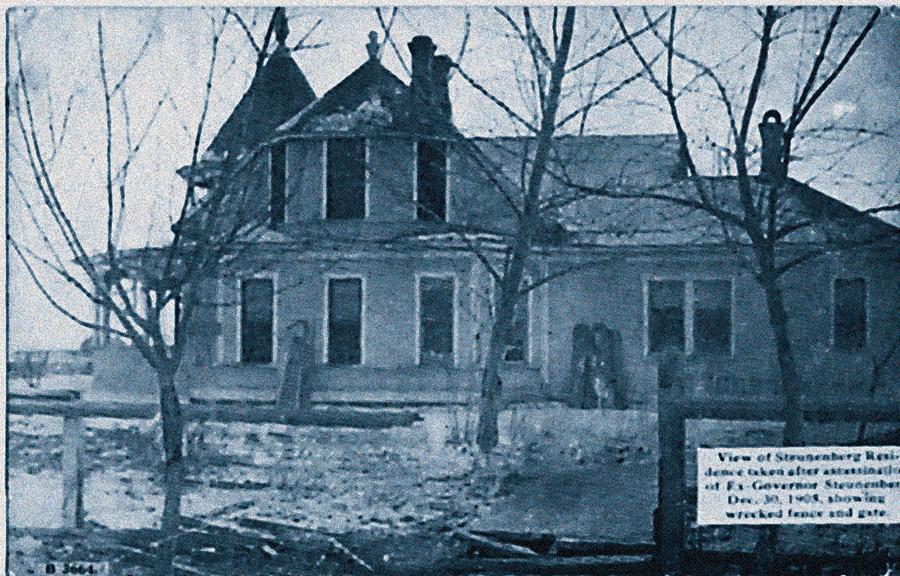

On December 30, 1905, Frank Steunenberg was walking home from his downtown Caldwell office. He opened the picket gate that led to the walkway to the house; as he closed it, a bomb was triggered. The blast shredded the lower half of his body. Family and friends carried him into his house—remarkably, he never lost consciousness—but he died within a few minutes. A search for his killer commenced immediately.

Locals quickly suspected a mysterious stranger who’d been in and out of Caldwell for three months. He called himself Thomas Hogan and said he was an insurance salesman—except he never sold any policies. Police questioned him; they also searched his hotel room, where they found elements commonly used in bomb making. On January 1, 1906, Thomas Hogan was arrested.

Going After the “Big Guns”

By January 10, the Pinkerton Detective Agency, at the request of local and state officials, had taken over the investigation. Western Division Superintendent James McParland personally ran the operation. On January 12, he met with the alleged assassin. And he got results. The alleged killer—who now admitted that his name was Albert Horsley, although he went by Harry Orchard—knew of the detective’s exploits, and in fact, he seemed to admire McParland. By the end of the month, the prisoner had given a full confession to numerous crimes, including the murder of Frank Steunenberg. He also confirmed one of McParland’s suspicions—that the leaders of the Western Federation of Miners ordered the hit.

So McParland went after the union men: Charles Moyer, president, “Big” Bill Haywood, secretary-treasurer, and former WFM board member George Pettibone. All three resided in the Denver area, which posed a problem. Extradition laws specified that only active participants in a crime could be sent from one state to another. Nothing was said about individuals who planned crimes but weren’t present during their commission. Technically, the labor leaders couldn’t be moved from Colorado to Idaho. McParland wasn’t about to let that stop him.

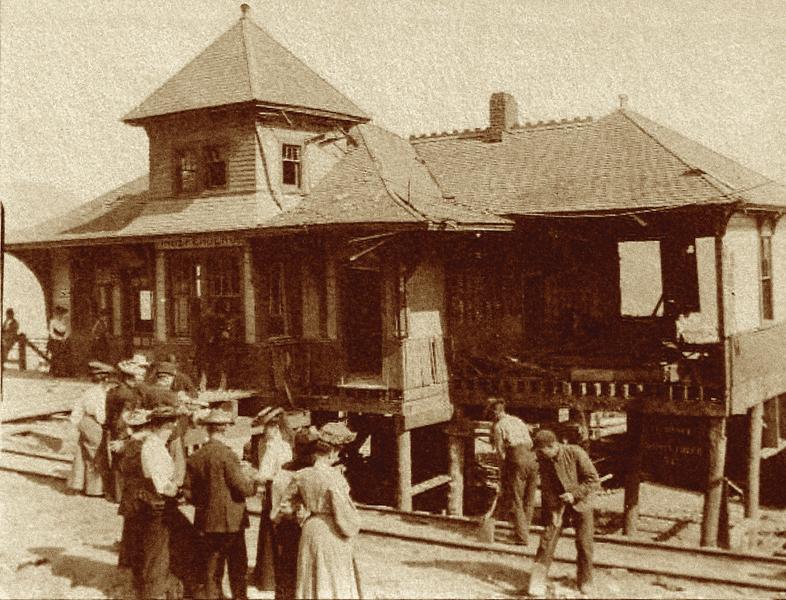

On February 17, the detective sent operatives to grab the three men (Haywood was taken from a boarding house where he was in flagrante delicto with his sister-in-law). They were taken to the railroad depot and put aboard a train. Just over 24 hours later, they were in Boise. But after that, the wheels of justice ran slow.

It was more than 14 months before the first trial got underway on May 19, 1907. Bill Haywood was the defendant; he was seen as the real power in the WFM, a firebrand who was capable of just about anything to get his way. His lead defense counsel was well known in labor and socialist circles but was not the international celebrity he would later become: Clarence Darrow. The prosecutors were the best Idaho could offer: newly elected U.S. Sen. William Borah, considered one of the top orators of his time, and James Hawley, who would later be elected governor.

The courtroom was packed every day. Journalists from around the world covered the proceedings. Organized labor and international socialism were on trial. A guilty verdict would be a huge blow to union movements in the U.S. and elsewhere.

The evidence against Haywood was slim—just Harry Orchard’s testimony. There was no corroboration (another suspect in the bombing initially admitted his role but later recanted). And Darrow had a field day with the bomber—he questioned his honesty and poked fun at Orchard’s claim that he’d been saved by Jesus during his time behind bars.

At the time, rumors spread that the defense stacked the deck by bribing one or two of the jury members, and there is some circumstantial evidence money changed hands. But if it did, the investment was overkill. The jury supported acquittal from the start of deliberations. They found Haywood not guilty on July 30. And that set the tone. George Pettibone was tried a couple of months later; he was found not guilty in January 1908. Charges against Charles Moyer were dismissed.

For his part, Harry Orchard was convicted of the assassination in March 1908. He got the death sentence, but the trial judge recommended it be commuted to life in prison and the state board of pardons agreed.

A Win for Labor

International labor rejoiced over the verdicts for Haywood and Pettibone, claiming victory and vindication for the union movements. General public opinion was a little different—most folks believed the men had gotten away with murder. Their suspicions about organized labor and its alleged ties to foreign anarchists and world socialism/communism only deepened. Ultimately, that led to problems for the unions. In 1917, local officials in Bisbee, Arizona, deported more than 1,000 striking copper miners to New Mexico (see p. 44). And in 1919-20, federal officials arrested numerous labor leaders for alleged anti-American activities. Some were deported to the Soviet Union. Big Bill Haywood went to Moscow voluntarily to live out the remainder of his life. America’s labor was on the ropes until the Great Depression in the 1930s and the huge surge in membership that came after WWII. But in the short term, the Steunenberg assassination was bad for unions.

But did Haywood, Moyer and Pettibone actually order the killing? The question has never been fully answered. One telling opinion was offered by J. Anthony Lukas, who spent years researching the case. The result was his 880-page tome Big Trouble, which came out during the 90th anniversary of the trial. Lukas was a left-leaning writer, likely pre-disposed to believe that the labor leaders were the victims of an attempted frame-up. Yet he came to the conclusion that they probably were guilty.

So the verdict of history seems to differ from that of the jury in this “Trial of the Century.” Try to say that about the Steunenberg Case.

Photo Gallery

– Illustrated by Frank Wiles in The Strand Magazine, May 1915; Poster of Charles Frohman’s original drama (Nov. 1899-June 1900) –

J. Anthony Lukas, a two-time Pulitzer Prize winner and author of Big Trouble, is credited with creating the term “barnyard epithet.” He was covering the Chicago 8 trial for The New York Times in the late 1960s and was trying to find a suitable replacement for “bullshit,” which the defendants frequently yelled at the judge.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

– All Images Courtesy of John Richards, great grandson of Steunenberg, unless otherwise noted –

In Boise, Idaho, at the “Idanha: Witness to History” exhibit, the 1901 Idanha Hotel (since converted to apartments) shares photographs and other information of the trial and people who stayed at the hotel. What famous people passed through these halls at that time?

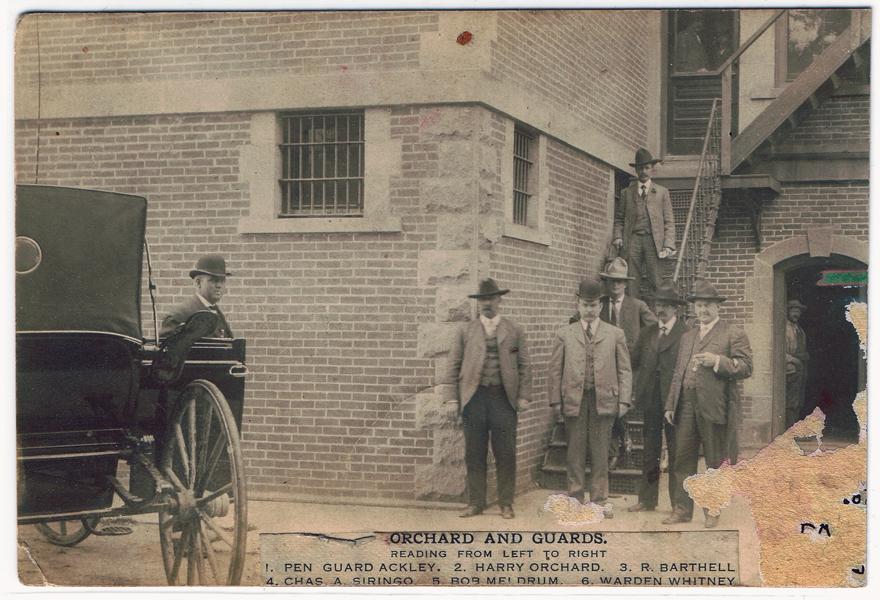

Famed cowboy detective Charlie Siringo served as a bodyguard for Pinkerton Western Division Manager James McParland. Bob Meldrum, a well-known gunslinger of the period, also provided protection. At one point, the two guards nearly got into a gunfight at the Idanha Hotel’s bar.

Future Hall of Famer Walter Johnson pitched for the minor league Weiser (ID) Kids. On one trip to the capital city, bad weather forced the team to practice inside the Idanha Hotel, where they were staying—Johnson threw batting practice in a second floor hallway, with a chamber pot serving as home plate.

Actress Ethel Barrymore, considered one of the great beauties of the age, enjoyed its hospitality when she came through Boise on tour and visited the trial—almost bringing the entire proceeding to a halt.

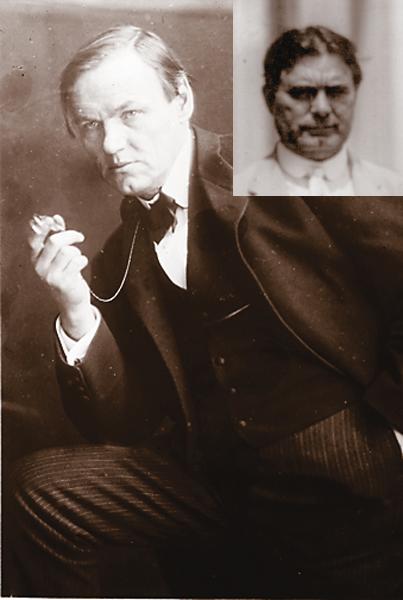

Harry Orchard is shown here at the Idaho State Penitentiary outside Boise. As you’ll note, Charlie Siringo is in this picture. So is Bob Meldrum, who was a pretty well-known gunslinger of the time. Both he and Siringo were serving as bodyguards for Pinkerton officials.

After confessing on the stand, describing the “unnatural monster I had been” in his career as a union terrorist, Orchard spent nearly 50 years in prison; he died in the Idaho pen in 1954. That was pretty unusual in the Old West, where “life” sentences frequently lasted less than 20 years. But the Steunenberg family—which remained politically powerful for years—pressured officials to deny parole.

Frank Steunenberg’s widow forgave her husband’s killer. Belle was a devout Seventh Day Adventist—some of her own family members thought she was a religious fanatic—and believed it was her duty to reconcile with Harry Orchard. He later said she was a key factor in his religious conversion. In fact, he became a member of her Boise church.

An overcrowded courtroom

– Courtesy Library of Congress –