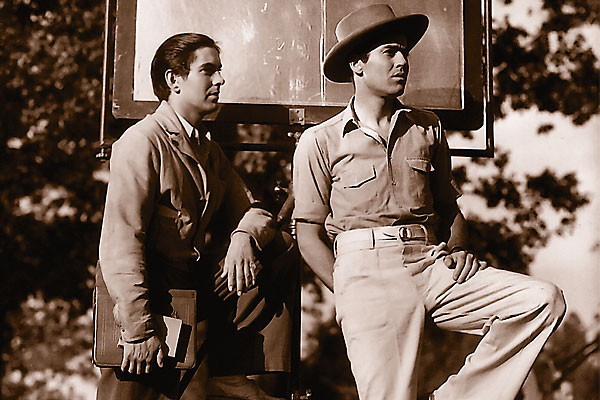

The best Jesse James movie is 2000’s Ride with the Devil, which isn’t about Jesse James. That’s okay because the best George Custer movie is Fort Apache, which isn’t about the Boy General.

The best Jesse James movie is 2000’s Ride with the Devil, which isn’t about Jesse James. That’s okay because the best George Custer movie is Fort Apache, which isn’t about the Boy General.

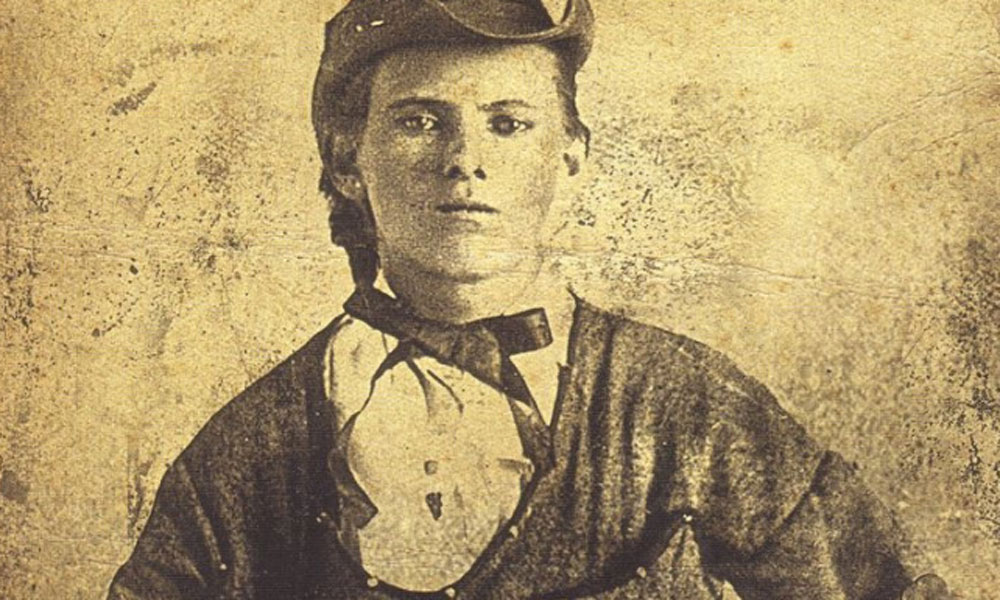

If you want to get down to real Jesse movies, the sad state of affairs is that for one of the most successful outlaws in Old West history, Jesse’s film career has been a mixed bag. Go figure. Hollywood can turn out classic (My Darling Clementine), rip-snorting (Gunfight at the O.K. Corral) and cult-favorite (Tombstone) films about a 27-second street fight, but it has never quite captured the story of a bad boy whose career spanned 16 years and even longer if you include his Civil War days. Buzz on the latest film, the on-perpetual-hold Brad Pitt vehicle The Assassination of Jesse James By the Coward Robert Ford (based on the best novel about the subject), suggests that history isn’t about to change.

“The problem with Jesse James and Hollywood is that studio heads and producers are businessmen and, to date, at least, they have seen no profit in portraying the real man,” says Frederick J. Chiaventone, an award-winning novelist, screenwriter and retired Army officer who taught counterinsurgency operations at the U.S. Army’s Command & General Staff College. “Painting a folk hero as a thug has little box-office appeal…. Hollywood has preferred to take the view espoused by the newspaperman at the end of John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance—to wit; ‘When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.’ The real Jesse James is, quite frankly, not a very romantic or even sympathetic character.”

Early James Films

About three dozen movies have tried to cash in on Jesse, the earliest being Essanay Film Company’s The James Boys in Missouri (1908). The most famous from the silent era was 1921’s Jesse James Under the Black Flag, which—for PR purposes—had good casting. Mesco Pictures of Kansas City offered Jesse Edwards James $50,000 to play his dad, but family, friends and critics agreed on one thing: Little Jesse was no actor. The movie was also a financial disaster, but the son, now calling himself Jesse James Jr., reprised the roll in 1921’s Jesse James as the Outlaw. It fared little better.

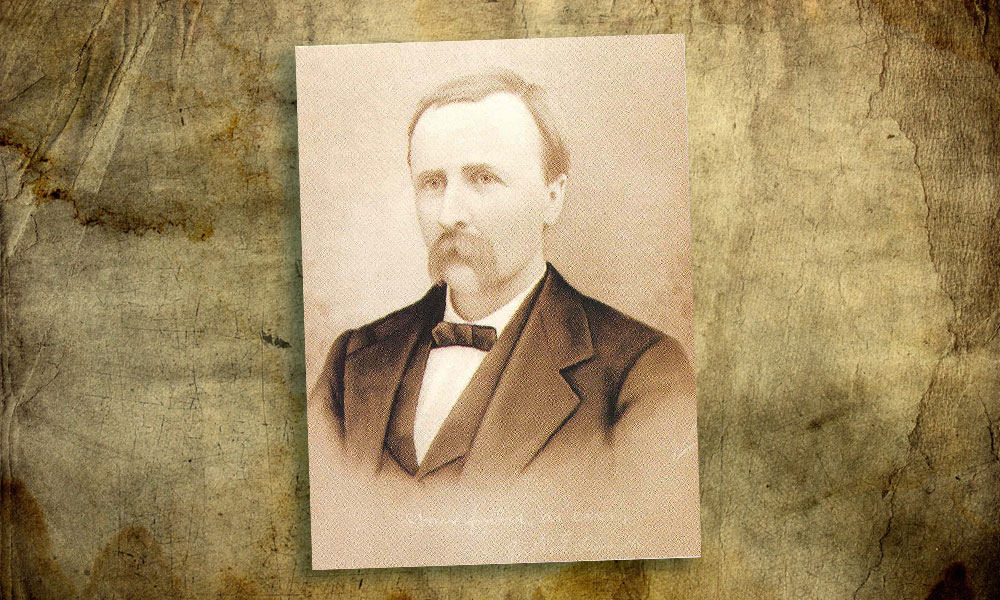

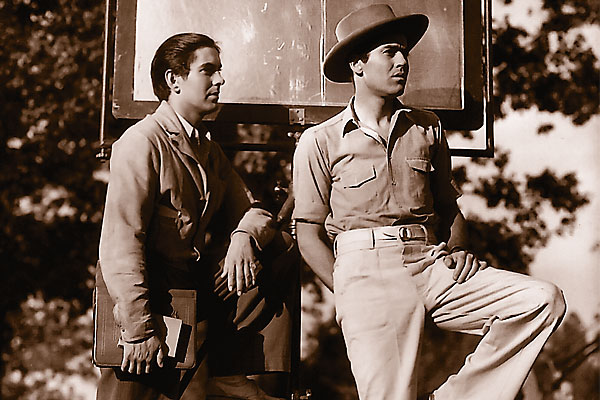

The most successful film came in 1939 with Jesse James, the first Western filmed in Technicolor, and starring Tyrone Power as Jesse and Henry Fonda—Hollywood’s best tobacco chewer—as brother Frank. The movie was filmed on location in Missouri but had little to do with history.

“About the only connection it had with fact,” Jo Frances James, Jesse’s granddaughter and a technical adviser on the movie, said, “was that there once was a man named James and he did ride a horse.”

Dated and hokey today, Jesse James earned enough money and good reviews to prompt a sequel, The Return of Frank James, with Fonda back in the saddle in a morality play, tracking down his brother’s killers. Critics weren’t as happy with this film: “…Fritz Lang has failed to make a successful compromise between a film that attempts to show the pressures that drove Frank James to robbery and murder or one that is honestly boots-and-guns horse opera,” Bosley Crowther wrote in The New York Times.

B-Oaters Take a Stab at Saga

For more than a decade after Return, the Jesse saga fell to mostly B-oaters. Roy Rogers, who had starred in 1939’s Days of Jesse James, played the outlaw in 1941’s Jesse James at Bay, and Clayton Moore of The Lone Ranger fame would try his hand in Jesse James Rides Again (1947) and Adventures of Frank and Jesse James (1948), two of three Republic serials, ending with 1949’s The James Brothers of Missouri with Keith Richards (not THAT Keith Richards) replacing the Lone Ranger.

Sam Fuller directed John Ireland as Robert Ford in 1949’s I Shot Jesse James, which The New York Times called a “dark, gloomy Western” but “commonplace.” Likewise, 1951’s The Great Missouri Raid with Macdonald Carey and Wendell Corey as Jesse and Frank—and scenery-chewing Ward Bond as the heavy—fared poorly. Yet two William Quantrill-inspired films, Kansas Raiders (1950) and RKO’s A-list Best of the Badmen (1951) proved respectable. Lawrence Tierney played Jesse in the latter (Tierney also played the outlaw in 1946’s Badman’s Territory with Randolph Scott, and Fuller wanted him for the Ford role in I Shot Jesse James), but the star of Badmen was Robert Ryan as a Yankee soldier framed for murder by Pinkerton agent Robert Preston.

Kansas Raiders cast Brian Donlevy as Quantrill and young Audie Murphy as Jesse. As film historian Robert Nott says, Murphy’s Jesse “eventually voices concerns and leaves the group before riding off into the sunset with a vow to come back to the leading lady. I don’t think Jesse James came back.”

Murphy would come back, though. He’d play Jesse again in a cameo in 1969’s A Time for Dying, his last movie.

A few B-flicks proved some entertainment—many more didn’t—even if they never came close to the truth. For instance, history tells us that Bob Ford didn’t lure Arch Clements and Jesse to Creede, Colorado, to go after a hidden fortune (as in 1953’s The Great Jesse James Raid). Nor was Frank, living peacefully in Creede, forced to go after Charlie Ford and a gunfighter who’s a dead ringer for Frank (as he does in 1950’s Gunfire). And Jesse wasn’t spurned by Belle Starr (who favors Cole Younger in 1960’s Young Jesse James). Yet in Gunfire, when Frank (played by Don Barry) says, “The outlawin’ died when Jesse died,” there is truth to that statement. By the way, Barry got a turn playing Jesse in 1954’s Jesse James’ Women.

Mistaken identity would be common in other Jesse movies. John Ireland plays a dead ringer for the late Jesse in The Return of Jesse James (1950), prompting Frank to come out of hiding and stop those fraudulent bad guys. And insurance salesman Bob Hope gets mistaken for the outlaw in 1959’s Alias Jesse James, a comedy that wasn’t that funny.

Hollywood tried another serious take on Jesse in 1957 with The True Story of Jesse James, only it wasn’t true; it was merely a remake of Nunnally Johnson’s Jesse James script. This one starred Robert Wagner as Jesse and Jeffrey Hunter as Frank, competent actors, certainly, but not in the Power-Fonda league. It earned mixed reviews. The New York Times called it “well-made”; Director Nicholas Ray called it “f—ing god-awful.”

A few gimmick movies followed, including a Jesse sighting in 1965’s The Outlaws is Coming with the Three Stooges. Of course, you can’t write about Jesse movies without mentioning 1966’s Jesse James Meets Frankenstein’s Daughter, labeled by many film critics as among the worst movies ever made.

Closer to the Truth?

Quasi-serious attempts at blending history with entertainment were resurrected with 1972’s The Great Northfield Minnesota Raid, starring Cliff Robertson as Cole Younger and Robert Duvall, who said he played Jesse as “a little queer.” “It’s neither conventional Western fiction nor completely documented fact, although it makes full use of history and is as crammed with the artifacts of 19th-century America,” Vincent Canby wrote in The New York Times. Reviews and box-office attraction, however, were lukewarm.

The same can be said of Director Walter Hill’s 1980 gimmick The Long Riders, casting brothers as brothers (David, Keith and Robert Carradine as the Youngers; James and Stacy Keach as the Jameses; Randy and Dennis Quaid as Clell and Ed Miller; and Christopher and Nicholas Guest as the Fords).

With only three Carradine brothers, brother John Younger got demoted to cousin, a historical mistake Hollywood repeated in 1994’s Frank and Jesse. That dreadful film gave Cole Younger (played by Randy Travis) only one brother. Must have been a budget issue.

Surprisingly, most Jesse biographers say the feature most faithful to history is 1986’s The Last Days of Frank and Jesse James, which covers the post-Northfield era—years, not days—and stars Johnny Cash as Frank and Kris Kristofferson as Jesse. The movie also featured cameos by David Allan Coe as Bill Ryan, Willie Nelson as Gen. Jo Shelby and poor June Carter Cash, forced to play Frank and Jesse’s mother. For some reason, Jesse filmmakers love Creede, and in this movie, Frank travels to Colorado in time to watch Ed O’Kelly shotgun Bob Ford to death. So much for history.

Any semblance to historical accuracy, not to mention good moviemaking, was thrown out the window when American Outlaws came out in 2001—a film so insipid, film critic Roger Ebert said it proved Hollywood couldn’t even make B-Westerns anymore. It tanked.

Okay, so why is Ride with the Devil the best Jesse James movie—even though Jesse James isn’t a character in it? Because it captures the mood and anarchy and, above all, the people of Civil War Missouri who helped shape Jesse and the boys. (Then again, I also have a soft spot in my heart for 1946’s Renegade Girl and 1940’s Dark Command.)

“Hollywood has yet to produce a film about Frank and Jesse James that is both historically accurate and entertaining,” says John J. Koblas, author of numerous histories about Jesse and company (see his James feature on p. 37). “For whatever reason, the James boys, more than any 19th-century desperadoes, have been shortchanged when it comes to telling the real story via the cinema.”

Maybe that’s because Jesse died young—unlike Wyatt Earp, who was shopping his life story around in Hollywood long before his death in 1929.

“Jesse James had no such friends because of a short life span,” Koblas says. “No one was left in the second half of the 20th century who had known Jesse, unless you consider Frankenstein’s daughter a true acquaintance.”