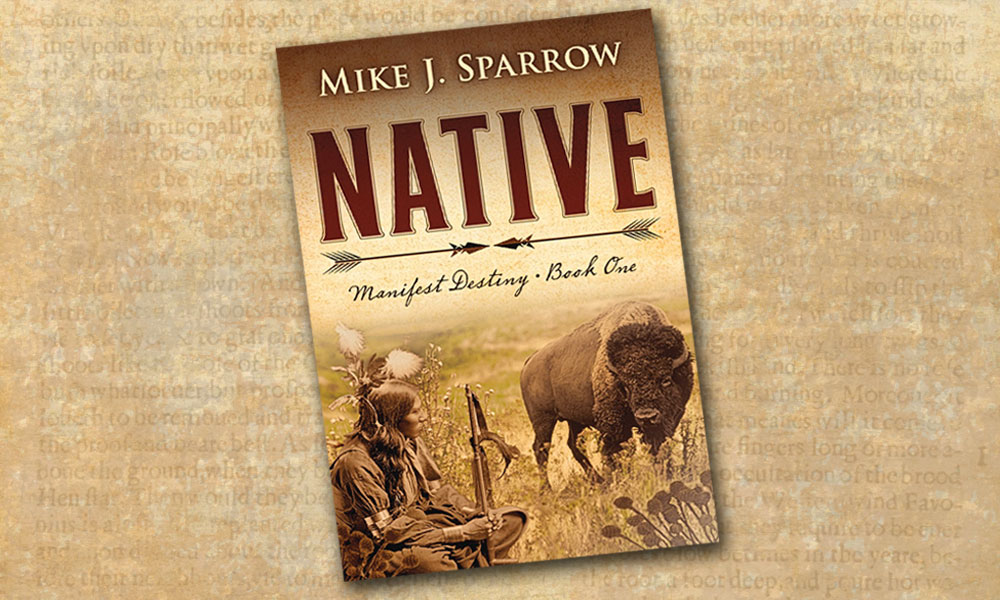

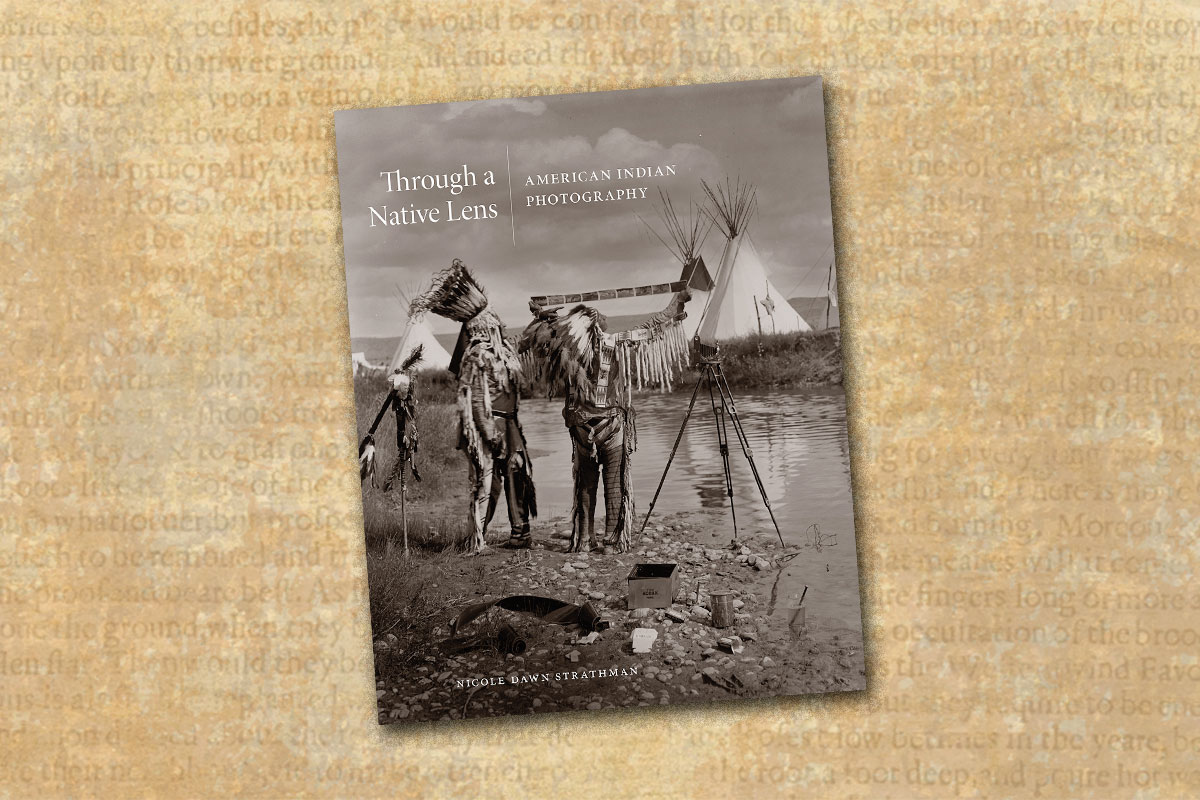

Following in the footsteps of the early 19th-century artists, photographers began to travel the West and record the places and people they encountered. One group of Westerners that fascinated and attracted the image-makers were America’s Indigenous peoples, who remarkably and consistently agreed to be drawn, painted and photographed. Forgotten to history was a group of American Indians who were inspired by the photographers they met to become photographers themselves. Nicole Dawn Strathman, a lecturer in art history at the University of California, Riverside, has researched and written a remarkable book, Through a Native Lens: American Indian Photography (University of Oklahoma Press, $50), that recounts the roles of the Native participants in photography and the Western Indian photographers. As Strathman notes in her introduction, “[I]n the latter half of the 19th century, American Indians were using cameras to record events from daily life and to remember tribal members…. But unlike the Western photographers of Native Americans, indigenous photographers generally did not emphasize or deemphasize the ‘Indianness’ of their subjects.”

Readers will be fascinated by the depth and breadth of Strathman’s research, which uncovered remote photographers including Inland Tlingit George Johnston of the Yukon Territory; Tsimshian Benjamin Haldane, who may have had the “first photography studio on a reservation, Annette Island Indian Reserve, in Metlakatla, Alaska;” and Crow/Scottish/adopted Cree Richard Throssel, who worked for the Bureau of Indian Affairs on the Crow Reservation from 1902 to 1911. The photographs by Johnston, Haldane and Throssel provide a window into the day-to-day life of tribes that was rarely allowed to be recorded by non-Indian photographers.

Strathman’s research also took her deep into archives across the West to uncover photos made by Native amateur photographers, a deeply personal and reflective group of unrecognized but important artists. In an attempt to provide as broad a continental scope as possible, the author focuses on five photographers: Kiowa’s Parker McKenzie and Nettie Odlety of the Phoenix Indian School; Cherokee Jennie Ross Cobb of the Cherokee Female Seminary School; Northern Paiute Harry Sampson of Nevada; and George Johnston of the southern Yukon. McKenzie and Odlety’s Kodak Brownie images include rare photos inside the girls’ dormitory, providing a different view of Indian boarding school life than is usually projected by historians.

What will readers conclude from Strathman’s Through a Native Lens? I believe the author’s research reflects back to us a personal connection to the human condition of Indian people of North America. And while we benefit from the images made by photographers such as Carleton Watkins, Timothy O’Sullivan, Edward S. Curtis and Frank A. Rinehart (see pages 34-41), who beautifully and empathetically recorded Indian life on film in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the photos of Indian people made by Native photographers provide a window into a more personal place of day-to-day life. As Strathman eloquently concludes, “In practicing photography, Native peoples have been able to harness the power of images to assert their own visual voices and to tell their own stories.”

—Stuart Rosebrook

A Legendary War Horse

In the annals of the Old West, few episodes have been explored more than the Little Bighorn battle. In author Janet Barrett’s Comanche And His Captain, The Warhorse And The Soldier of Fortune (Tall Cedar Books, $18.95), the stories of this horse, the only survivor of the battle on the Army’s side, and his master, 7th Cavalry Captain Myles Keogh, are finally told. While much information about Keogh’s adventurous life as a professional soldier is available, little has been told of his mount, Comanche. Once the most famous horse in America, this tough little Texas mustang’s life from the time of his 1868 purchase by Keogh—as a six-year-old at a St. Louis Army horse depot—to his 1891 passing as a beloved symbol and “Second Commanding Officer” of the 7th Cavalry, is related as thoroughly as is possible. It should be included in any collection of Custer’s cavalry.

—Phil Spangenberger, True West’s Firearms editor

An Alamo Adventure

Mark C. Jackson’s character, Zebadiah Creed, in The Great Texas Dance, “Tales of Zebadiah Creed, Book 2” (Five Star, $25.95), lives by his own moral code. At the Alamo in 1836, Creed and best friend, Grainger, are sent off with a plea for reinforcements from Gen. Sam Houston. Within two days, the Alamo falls to the Mexicans. Safe for now, Creed gives the message to Houston, who counters with another errand. Along the way, Creed befriends a young boy, and they both learn about friendship, deceit, loyalty, slavery and war. While much has been written about the actual Alamo siege, this novel from the point of view of a messenger, fills in holes which help round out the story. Filled with tantalizing descriptions and wild action, The Great Texas Dance is, in this reviewer’s opinion, one of the best Western novels ever written.

—Melody Groves, author of When Outlaws Where Badges

Forgotten Deputy U.S. Marshal

George Tucker is one of those forgotten lawmen of the Wild West who has

a record worthy of modern media ex-ploiting his name. He was a lawman in Montague County, Texas, surviving numerous gunfights, and then became a deputy U.S. marshal working out of Paris. He was one of many lawmen enforcing the law on both sides of the Red River. In 1892, the call came for fighting men to go to Wyoming Territory to protect the interests of big cattlemen, and Tucker answered the call. In his later years, Tucker wrote his memoirs; historian Norman Wayne Brown has combined his own research into Tucker’s life with the memoir and has produced the fascinating narrative Man Hunter in Indian Country: George Redman Tucker Deputy U.S. Marshal (Eakin Press, $19.95).

—Chuck Parsons, author of Texas Ranger Lee Hall: From the Red River to the Rio Grande

The Power of the Western Stage

Carolyn Grattan Eichin’s From San Francisco Eastward: Victorian Theater in the American West (University of Nevada Press, $60) is a scholarly, insightful, meticulously researched and documented study of Victorian theater in the West as a reflection of the American melting pot. The author demonstrates the theater’s importance as an “agent of cultural change and regional identity” and shows how it created “homogeneity from a heterogeneous culture,” and acted as a “democratizing influence upon the West.” Adopting a feminist perspective, Eichin focuses on the theater’s empowerment of women and the tensions between working-class audiences and respectable middle-class audiences. Eichin’s erudite analysis, a feast for socioeconomic historians, won’t appeal to casual theater buffs, but it is the best, most thought-provoking study of the subject to date.

—Tom Collins, author of Louis James: America’s Titan of the Shakespearean Stage, 1875-1910