If you’d visited San Francisco back in 1967, you might have found a 14-year-old kid doing something a bit unusual for a teenager.

He spent time in libraries, poring over old documents, photos and newspapers. He was on the trail of the legendary California bandit Tiburcio Vasquez.

Today, the decidedly grown-up John Boessenecker has finished the research and come up with the definitive book on the outlaw, Bandido: The Life and Times of Tiburcio Vasquez, published by University of Oklahoma Press.

So what led a teenager to study Vasquez? “I’d heard lots of stories about him, growing up in northern California where he spent most of his life. And I was also interested in California during that period. The rise of Vasquez the bandit coincided with the fall of the Californios, the Latinos who populated the area.”

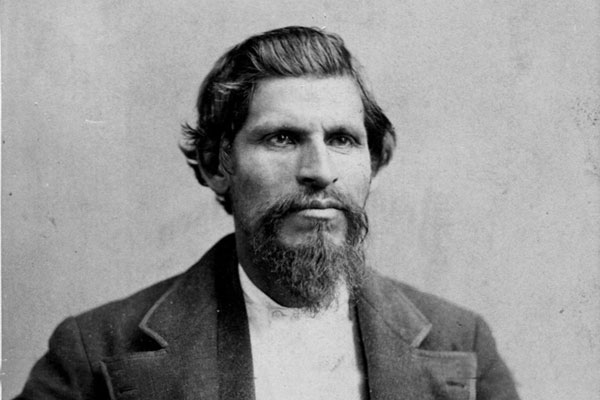

Vasquez certainly didn’t seem a candidate for a life of crime when he was born in 1835. His great-grandfather helped found San Francisco. His grandfather was one of the first settlers in San Jose, where he was the alcalde (chief administrator) three times. Vasquez’s father served as a councilman in San Jose. Tiburcio’s family wasn’t wealthy, but it was prominent. Folks expected him and his brothers and sisters to follow that same path.

But like the old story goes, the young Tiburcio fell in with bad company; he hit the outlaw trail by the time he was 17.

Vasquez’s criminal career was a long one, stretching from about 1852 until his death in 1875 (with a couple of prison stints in the interim). He became something of a legend in his own time.

And why not? In a world where most criminals were ugly, dirty and semi-crazy, Vasquez stood out. “He was a true gentleman bandit,” the author says. “He was handsome, friendly and talkative, dressed well, sang and played guitar, and danced. He was well educated.”

Vasquez had charisma. Many of his fellow Californios, then and now, embraced the legend of Tiburcio as a freedom fighter and social bandit. The stories say he was a Robin Hood, stealing from the rich gringos to give to the poor peons. Vasquez encouraged that image: “I had numerous fights in defense of what I believed to be my rights and those of my countrymen.” Health centers and schools are named for him.

Boessenecker’s response? “Why did he rob people? So he could get money to spend on himself.”

Vasquez and his gang held up stagecoaches, stores, travelers—anybody that might have a fat purse. The man could be bold, such as when his outfit held up the entire town of Kingston on December 26, 1873, and stole $2,500 in cash and jewelry.

His sprees weren’t always violence-free. An August 1873 raid on a store in Tres Pinos resulted in the deaths of three innocent bystanders—and increased rewards for Vasquez’s capture.

His passion for women would lead to his downfall. Vasquez had countless lovers and illegitimate children. But he made some seriously bad decisions when it came to his amours.

Vasquez angered members of his own family when he impregnated his teenage niece. He later stole the wife of one of his trusted lieutenants. People turned against him, leading to his capture in Los Angeles in May 1874. A jury convicted him of murder. On March 19, 1875, he was hanged in San Jose—ironically, the same city founded by his grandfather.

The publication of Bandido is the end of a long trail for Boessenecker, who is a prominent attorney in San Francisco. But it’s not the end of his writing career (he is the author of several books on Old West outlaws and lawmen). His next book is a bio of Arizona sheriff (and Earp ally) Bob Paul.

That shouldn’t take more than four decades to complete.