Michael Wallis’s first outlaw biography was on Oklahoma’s social bandit Pretty Boy Floyd, published in 1992. Now he’s written Billy the Kid:

The Endless Ride (W.W. Norton), which brings into focus the legend of the frontier’s more enigmatic figure.

TW: What attracted you to writing a biography of someone about whom so little is actually known?

MW: That is not necessarily the public perception [of the Kid] due to the countless books, articles and motion pictures devoted to the illusive young man. The truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth about the Kid is difficult to find and twice as hard to prove—he is like quicksilver. For that reason, I was drawn to this deeply mythologized young man who will be 21 years old forever and remains an enigma to this day. I do believe, however, that the Kid will continue to attract writers and researchers. Perhaps some lost correspondence, a hidden diary or photograph will emerge. I only hope that my book helps shed some light on the life and times of the Kid, and helps explain how this cultural icon could ever exist.

Larry McMurtry has said factual information on Crazy Horse would scarcely fill a page. Billy has left us a little more than that, but not a great deal more. What were your basic source materials for The Endless Ride?

Despite the fact that so much has been written about the Kid, most people would be astonished to learn just how much of it is pure conjecture and often outright lies. I realized the daunting task I faced based in part on my experiences when writing the biography of another American outlaw—Charles Arthur “Pretty Boy” Floyd. Like the Kid, Floyd was also greatly mythologized and, depending on the circumstances and the source, was either described as the devil incarnate or a sagebrush Robin Hood. In the case of both of these young men, the true stories of their brief and violent lives lie somewhere between heaven and hell on human terra firma.

I read as much about the Kid as I could get my hands on but was careful to filter out the obvious distortions and exaggerations. Instead I turned to the careful work of a few diligent authors and researchers before me, such as Robert Utley, Jerry Weddle, Frederick Nolan, John Wilson, William Keleher and Bob Boze Bell. I scoured many of the archives, collections and libraries as the more credible primary sources had done and also probed new material that has more recently surfaced. I also looked into areas of the Kid’s life and particularly his times that have not been fully pursued in the past, such as aspects of his boyhood, his close association with the Hispanic population and the influence of the Masonic order on the Lincoln County War.

I considered many of the earlier written works about the Kid—including some purported biographies—to be mostly works of fiction. That includes Pat Garrett’s ghostwritten tome about Billy the Kid that was published shortly after Garrett’s deadly meeting with the Kid in Pete Maxwell’s bedroom at Fort Sumner. Garrett’s sensationalistic book about the young outlaw is not only self-serving but unfortunately became a primary reference for a slew of others who penned their own tales and accounts of the Kid. I look at the Garrett book as a piece of literary history but not at all trustworthy as a source of fact.

Much wasn’t written on Billy in the 20-odd years before Burns’ book was published in 1925. Do you regard Burns as an important part of Billy’s myth- making process?

Clearly the publication of The Saga of Billy the Kid by Walter Noble Burns in 1926 revived interest in the life of the Kid and was largely responsible for perpetuating much of the myth clouding the truth about him that survives to this very day. Yet even though the Burns bestseller contains its share of fiction and was greatly influenced by Pat Garrett’s dubious biography of the young man he shot to death in 1881, The Saga of Billy the Kid has great value. Within its covers are accounts provided to Burns from survivors who knew the Kid during his fleeting and tumultuous life. This book sparked the public’s interest by presenting the Kid as a tragic scapegoat as opposed to the crazed homicidal maniac many other writers made him out to be. I believe Burns’ biography profoundly influenced future generations of historians, screenwriters and even famed composer Aaron Copeland, who crafted an entire ballet about Billy the Kid in 1938.

Of all the great Old West legends, the Kid has been the most popular with artists and writers. In addition to Copeland, I’m thinking of the poet, Michael Ondaatje, who wrote The Collected Works of Billy the Kid, Gore Vidal, who wrote two plays about him, and novelists such as Larry McMurtry and N. Scott Momaday. Why do you think Billy appeals to creative folks?

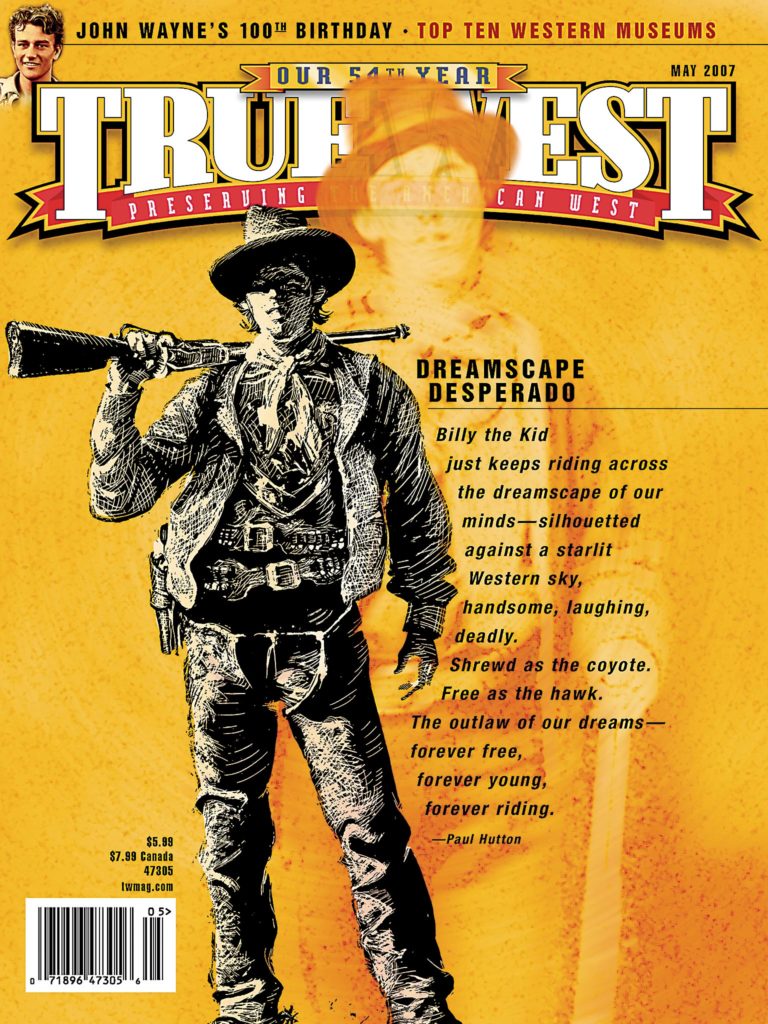

Billy the Kid will always capture the public’s imagination. That’s a safe wager, and not just because of all the biographical documentaries and nonfiction portraits of his life and times that keep his story alive. Creative artists have fueled the legend of Billy the Kid. Some portray him as a dark and satanic figure and others as a martyred symbol of righteousness. In addition to those you mention, the long list of those who have left their own interpretation of the Kid include Zane Grey, King Vidor and Sam Peckinpah. Besides composer Aaron Copeland, the Kid has been the subject of songs from Woody Guthrie, Bob Dylan, Jon Bon Jovi and Billy Joel.

For all of these artists and more to come, the story of the mysterious young man who died so young is as relevant today as it was when he lived. It is a purely American story that endures and still fascinates, perhaps in part through the conversion of fantasy into historical fact. Billy the Kid allows all who choose to interpret his life an opportunity to tread the ground where the American West of myth collides with the American West of reality. That chance is most compelling and very seductive. It is also why the Kid will ride on forever. Henry McCarty was shot dead in 1881, but Billy the Kid survived.

Allen Barra is a contributing editor for American Heritage magazine and the author of Inventing Wyatt Earp, which has been in print since its publication in 1998.