Legendary figures in the Old West came about gaining public recognition in a variety of ways. Many came about it by self-promotion. Some, like Custer and Billy the Kid became legends after they died with their boots on. Others, like Jim Bridger and Kit Carson were glorified by dime novelists like Ned Buntline. Pauline Weaver, Ewing Young and Tom Fitzpatrick were great pathfinders never got the recognition they so richly deserved but perhaps the most deserving of them all was Antoine Leroux. The only monuments in Arizona that I’m aware of to Leroux today are Leroux Springs in the San Francisco Peaks, a street in Flagstaff and Leroux Wash near Holbrook.

Legendary figures in the Old West came about gaining public recognition in a variety of ways. Many came about it by self-promotion. Some, like Custer and Billy the Kid became legends after they died with their boots on. Others, like Jim Bridger and Kit Carson were glorified by dime novelists like Ned Buntline. Pauline Weaver, Ewing Young and Tom Fitzpatrick were great pathfinders never got the recognition they so richly deserved but perhaps the most deserving of them all was Antoine Leroux. The only monuments in Arizona that I’m aware of to Leroux today are Leroux Springs in the San Francisco Peaks, a street in Flagstaff and Leroux Wash near Holbrook.

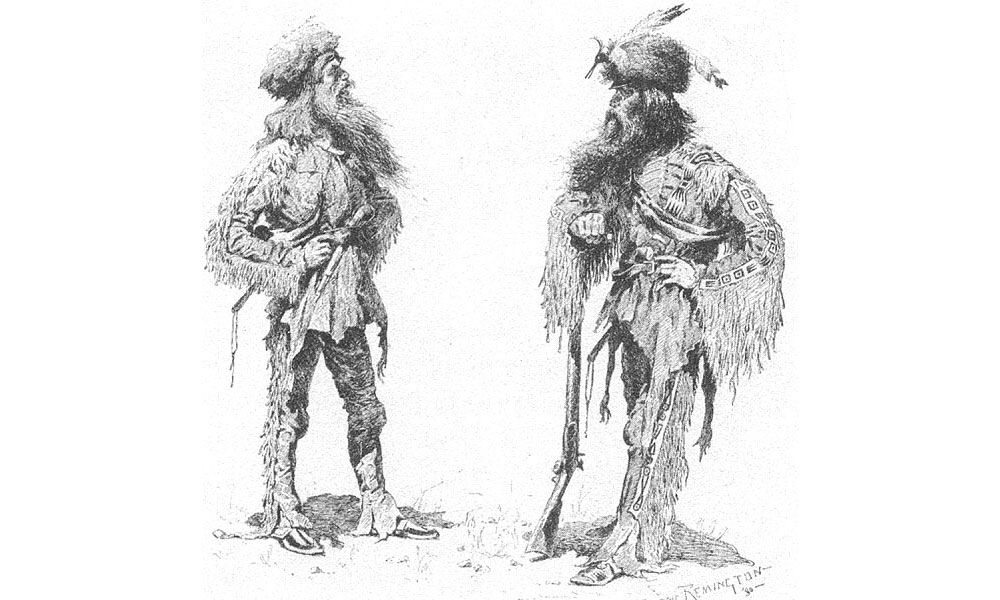

He had a sense of adventure that took him to the far reaches of the Wide Missouri with the likes of Jim Bridger, Jedidiah Smith, Tom Fitzpatrick and the other members of the famous 1822 Ashley-Henry voyage up to explore the headwaters of the Missouri and become part of a unique American breed known as free trappers.

Unlike many who were recruited from the grog shops of St. Louis to make that historic voyage up the Missouri, Leroux was a member of an affluent French merchant family and educated in the finest St. Louis academies.

In 1824 Leroux was trapping in the Gila watershed of Arizona and New Mexico. He trapped with and was friends with men like Old Bill Williams and Kit Carson. And he found the time to marry a beautiful young heiress to a half-million-acre land grant.

By the time the Americans took over the region in 1848, Leroux was considered the most experienced, competent and celebrated scout and guide in New Mexico.

In 1846, during the Mexican War he was a guide for the Mormon Battalion on its historic road-building trek from Santa Fe to California. In 1851 he guided the Captain Lorenzo Sitgreaves Expedition across northern Arizona. While camped on the west end of the San Francisco range Leroux suggested they name a mountain after his old friend Bill Williams. Today, the town of Williams lies at the foot of that mountain

A few weeks later, over on the Big Sandy River in today’s western Arizona, Leroux walked into and ambush and suffered three arrow wounds. It was said the humiliation of getting ambushed was more painful to the battle-toughened old scout than the arrow wounds.

The expedition was the first of several by the Army Corps of Topographical Engineers charged with locating future transcontinental railroad routes to the West Coast. Of the four proposed routes and all are still in use today, Leroux was the guide on three.

The following year he joined John Russell Bartlett’s and Lt Amiel Whipple the “workhorse of the Boundary Expedition,” surveying along the Mexican border.

Soon after that he was with Whipple again, this time mapping a route across northern Arizona that would eventually become Route 66, (today’s Interstate 40) and the Santa Fe Railroad.

One of the most intriguing stories about the Antoine Leroux story went back some 50 years before he was born. His grandmother was a woman named Maria Rosalia Villapando, the daughter of a wealthy Mexican rancher. During a Comanche raid on the ranch in 1760 she was among 56 women and children taken prisoner. All the men were killed. In time she was sold to the Pawnee.

One day a French trader from St. Louis named Jean Baptiste Lajoie saw the beautiful woman and fell madly in love with her. He ransomed her from the Pawnee and took her to St. Louis where they were married. The couple raised two daughters. One of the girls, Helene, later married a French merchant named William Leroux and they had four children. The youngest, Antoine, was born in 1801.

When Antoine Leroux arrived in New Mexico in 1824 he completed the circle of a tragic incident that was known as one of the bloodiest massacres in New Mexico history. The enduring Maria Rosalia lived to be 107 years old.

The Villapando’s remain one of New Mexico’s most illustrious families.