— Illustration by Bob Boze Bell —

General Crook is leading the Big Horn and Yellowstone Expedition, which consists of some 990 cavalry and mule-mounted infantry, 250 friendly Indians, 36 packers and Montana miners, and six journalists. Crook’s chief scout is Frank Grouard. The wretch Calamity Jane was left behind at Goose Creek.

The soldiers are resting when they start to hear firing from the bluffs to the north, where Crow and Shoshone scouts are positioned. The troops at first assume the friendly Indians are shooting buffalo (the day before the scouts jumped a buffalo herd and started firing, disobeying Crook’s orders to abstain from making such a ruckus). As the firing increased, Crows rush through the camp shouting, “Heap Sioux! Heap Sioux!” Heavily outnumbered, the Crows and Shoshones fall back towards Crook’s main assembly.

Reacting to the opening salvos, Crook directs his forces to seize the high ground to the north and south of Rosebud Creek. He orders Capt. Frederick Van Vliet of the Third Cavalry to take the high bluffs south of the creek to guard against an Indian attack from that direction. The general then commands Maj. Alex Chambers and Capt. Henry E. Noyes to form a dismounted skirmish line and advance towards the attackers.

Crook orders Capt. Anson Mills and his Third Cavalry to charge the Lakotas. Mills’s charge effectively unnerves the Indians in that sector and they withdraw to the next ridge line. Mills re-forms his troops and leads another charge, driving the Indians farther north. Poised to attack again, Mills receives orders from Crook to cease his advance and assume a defensive position.

Chambers and Noyes, meanwhile, soon join Crook as he advances up the Camel-Back Ridge and establishes his headquarters. From there he sends three infantry companies to a prominence even farther west, and then considers his next move.

After initially falling back, the Lakotas and Cheyennes keep up long distance firing and small parties engage in hit-and-run tactics. Crook, ever anxious to strike the Indian village, orders Mills and Noyes to swing eastward to the Big Bend and follow the Rosebud north to find the village, which in nearness, Crook believes, is causing the Indians to be so tenacious about holding their ground.

While Mills and Noyes are making their way down the Rosebud, Lt. Col. William Royall and five companies of cavalry advance on warriors along Kollmar Creek, a small dry Rosebud tributary. When Crook sees the danger of Royall’s advance he sends orders for Royall to withdraw to Crook’s Hill. Royall at first sends only one company, while the rest of his men remain fully engaged. For a second time Crook orders Royall to withdraw and when he about-faces all hell breaks loose. Eventually Crow and Shoshone scouts show up and drive the Lakotas and Cheyennes back. Crook also details two infantry companies to occupy a nearby hill to aid Royall. The friendly scouts and those long-range infantry rifles probably saved Royall’s command from complete destruction.

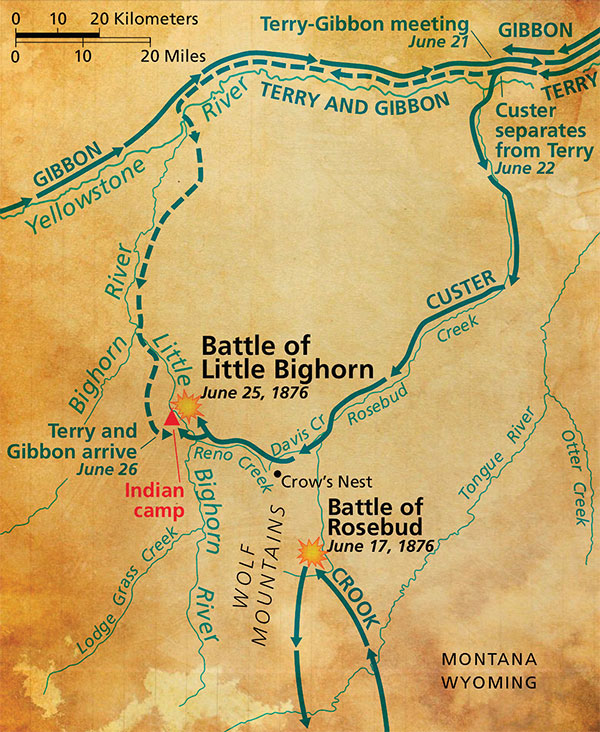

In the early afternoon Royall finally completes his withdrawal. Fearing utter calamity, Crook also withdraws Mills and Noyes from their advance on the village, and when those troops return to the field the Sioux and Cheyenne break off their fight and return to Reno Creek. It’s mid-afternoon and the Battle of the Rosebud is over.

On The Trail With Crook

Historian and author Paul Hedren makes the point that Rosebud “may well be the largest Indian battle ever fought in the American West.” The physical scale of the fight is colossal with three different clashes taking place across a battlefield that was miles wide and miles long.

The Rosebud battlefield is perhaps unique because Crook had with him five full-time newsmen and a full-time illustrator in the field and at the battle.

On June 14, 175 Crow and 86 Shoshoni show up with Frank Grouard. Two days later, on June 16, Crook leaves the wagons and pack train behind with most of the cilivians and advances northward across the Tongue River to seek and engage the Lakota and Cheyenne warriors. The element of surprise was destroyed when the Crow and Shoshoni scouts jumped a buffalo herd and shot many of them. An Indian force of close to 1,000 Indians rides all night and comes into contact with Crook’s scouts at 8:30 a.m. on June 17.

By the standards of Indian warfare, the Battle of the Rosebud was a long and bloody engagement. The Lakota and Cheyenne fought with persistence and demonstrated a willingness to accept casualties rather than break off the encounter. The delaying action by Crook’s Indian allies during the early stages of the battle saved his command from a devastating surprise attack. The intervention of the Crow and Shoshone scouts throughout the battle was crucial to averting disaster for Crook.

Aftermath: Odds & Ends

The Indian force, led by Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull, numbered 750 to 800 mounted warriors and it is safe to say they were armed to the teeth with modern weapons. Casualties on both sides were relatively light with Crook claiming he lost 10 killed and 21 wounded. However his aid Lt. John Bourke reported that four of the wounds were mortal and he gave total casualties as 57. Crazy Horse later said that the Lakota and Cheyenne casualties were 36 killed and 63 wounded.

Crook’s bruised command returned to Goose Creek on June 21, carrying their wounded on travois. The wounded were then taken to Fort Fetterman for treatment. His Crow and Shoshone scouts left the command but promised to return.

On June 22, Crook, Capt. Frederick Van Vliet, Capt. Andy Burt and others went on a hunting and fishing trip.

Eight days after the Rosebud battle, Custer, commanding eight companies of the Seventh Cavalry, strikes Sitting Bull’s village on the Little Big Horn and is wiped out. From that moment on, Crook’s actions have been questioned; he should have done more.

Recommended Rosebud June 17, 1876: Prelude to the Little Big Horn by Paul L. Hedren, published by University of Oklahoma Press.