November 3, 1883

November 3, 1883

It’s a Saturday as the Sonora-Milton stage rattles along, empty, save for the driver. Reason E. McConnell has been on the road for three hours since he stopped at the Patterson Mine, near Tuttletown, California, picking up $4,200 worth of amalgamated gold. The Wells Fargo box also contains $500 in gold coin and $64 in raw gold.

McConnell finally reins up in front of the Reynolds Ferry Hotel, nestled along the banks of the Stanislaus River. Jimmy Rolleri, the hotel manager’s 19-year-old son, exits the hotel and exchanges the outgoing mail for the incoming. Glancing at the empty coach, Rolleri asks if he can catch a ride up the hill on the opposite side of the river. A traveler who had stopped at the hotel the previous night reported seeing “two big bucks up there on the flat above Yaqui Gulch,” he says.

McConnell tells the boy to grab his gun, and Rolleri returns with a “well-worn but serviceable .44 Henry rifle.” With the help of Henry Requa, the two successfully ferry the stage across the river. Requa returns the ferry to the hotel side of the river, and Rolleri jumps up on the box with McConnell, who slaps the reins of his team, encouraging them up the steep approach to Funk Hill.

Halfway up the long grade, Rolleri asks McConnell to slow down. He jumps off with his rifle, thanks McConnell for the lift and heads out into the underbrush to hunt for the big bucks.

The six-horse team continues on, struggling up the steep grade for another 30 minutes. As the stage rounds the head of Yaqui Gulch, with the ridge line in sight, the lead horses snort and rear in fright when a lone, hooded figure, shotgun in hand, leaps into the roadway.

Wearing a dirt-smudged duster and a flour sack with eye holes cut into them, the highwayman demands the Wells Fargo box be thrown down. McConnell informs the robber it’s bolted down. The outlaw tells the driver to unhitch his team, but McConnell protests, fearing the stage will roll down the hill due to its bad brakes. The robber’s solution is for McConnell to wedge rocks behind the wheels, but the driver brashly pushes his luck by stating, “Why don’t you do it?”

Incredibly, the hooded robber keeps his shotgun trained on the driver, picks up several stones and blocks the back wheels. McConnell then unhitches the team and leads it uphill. “If you don’t want to get shot,” the robber warns him, “don’t come back or even look back in this direction for at least one hour.”

While leading the team, McConnell hears the robber banging away at the strongbox. Sneaking glances toward the coach, he can’t see the brigand, who has probably crawled into the stagecoach.

Two hundred yards from the stage, McConnell stops to catch his breath when downhill movement catches his eye. It’s Jimmy Rolleri, the Henry rifle in the crook of his arm, moving across an open swale of land about 300 yards below. Tying his team to an oak tree, McConnell runs downhill as quietly as he can, frantically waving his hat until he gets Rolleri’s attention. Coming up the hill, Rolleri first thinks McConnell has discovered the deer. But the driver fills him in on the situation, and the two warily approach the stage with the intent of capturing the outlaw, or killing him. When they get within 100 yards, the bandit suddenly emerges from the stage and spots them. The outlaw throws a sack over his shoulder and starts to run.

McConnell borrows Rolleri’s rifle and fires twice, missing the robber both times.

“Here, let me shoot,” young Rolleri says. “I’ll get him and I won’t kill him, either.” With Rolleri’s shot, the outlaw stumbles, but he vanishes into the underbrush with his booty.

When the county sheriff and a Wells Fargo detective arrive, they discover what the brigand left behind in his hasty retreat: a derby hat, three pairs of cuffs, an opera glass case and a silk crepe handkerchief with the laundry mark “F.X.O.7.” on it.

After eight years and 28 successful stage holdups, this last item will prove to be Black Bart’s undoing.

A Dapper Disguise

A Dapper Disguise

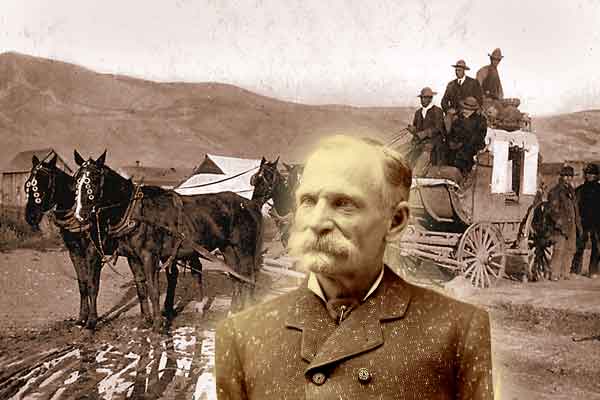

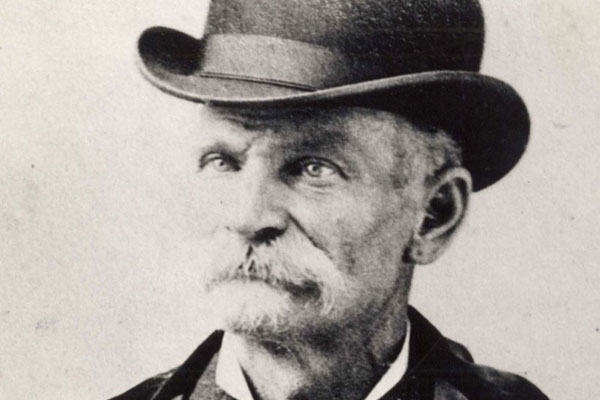

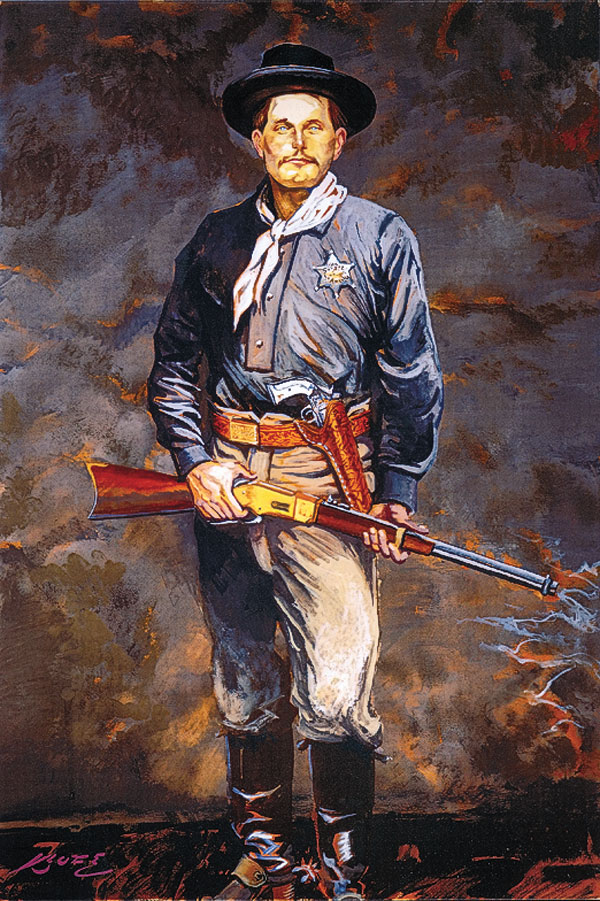

Looking more like a banker than a common stage robber, Black Bart cuts a distinguished figure around San Francisco (his hideout), where he poses as a mining investor named Charles Bolton.

The Monday after the stage robbery, Detective Harry Morse begins matching laundry marks from a handkerchief left at the scene with those of the 91 laundry centers in San Francisco. By the afternoon, he has a match. When a nattily-dressed suspect is taken to Wells Fargo headquarters, the agents are shocked as he looks like “anything but a stage robber.” By the end of the week, Black Bart confesses and leads officers to the buried gold. He also poses for the above photograph.

By all accounts, the bandit is witty, self-effacing and intelligent. He even writes a letter from prison to Reason McConnell, who he thanks for being such a lousy shot. He ends the warm letter with: “You sir, have my best wishes for an unmolested, prosperous and happy drive through life.”

Where He Got the Name

The infamous robber refused to acknowledge that his real name was Charles E. Boles and served his prison term as Charles E. Bolton.

As for the nom de plume “Black Bart,” Boles admitted he got the name from a character in William Henry Rhodes’ “The Case of Summerfield,” an 1871 serial that ran in the Sacramento Union. Boles admitted, “when I was casting around for a pseudonym, the name just popped into my head.”

Legendary Poetry

Although Black Bart only leaves two poems at the scenes of his robberies, they contribute to his legendary fame. Some described them as “doggerel,” but one thing is certain: He had an excellent sense of humor.

Here I lay me down to sleep

To wait the coming morrow

Perhaps success perhaps defeat

and everlasting sorrow.

Let come what will. I’ll try it on

My condition can’t be worse,

But if there’s money on the box,

It’s munny in my purse.

—Black Bart, the P o 8.

Aftermath: Odds & Ends

On November 17, 1883, Charles Bolton, alias Black Bart, pleaded guilty to a single charge of robbery and was sentenced to a remarkably light term of six years in San Quentin. With time off for good behavior, he was released after serving four years and two months.

The newspapers had a field day charging that Black Bart made a deal with the officers in exchange for the stolen gold. Harry Morse suffered the harshest criticism, as the papers questioned his version of the arrest and insisted that an informant had actually led Morse to Bart. One paper, The San Francisco Examiner, even questioned whether Boles was Bart.

Wells Fargo paid Morse and Calaveras County Sheriff Ben Thorn the bulk of the $800 reward. Then Thorn and Morse got into a public spat, accusing each other of malfeasance in the case. Thorn got the final salvo when he publicly reminded Morse of his bragging about an extra-marital affair during their ride from San Andreas to recover the stolen gold. It was a low blow from Thorn, but it worked. Morse never responded.

Black Bart was released from prison in January of 1888. By mid-year, he was back in the news after three more stage holdups, in which Black Bart was named by Jim Hume as the main suspect. Boles disappeared for good. Even his long suffering wife never heard from him again.

Recommended: Black Bart: Boulevardier Bandit by George Hoeper, published by Word Dancer Press; and Lawman: The Life and Times of Harry Morse, 1835-1912 by John Boessenecker, published by University of Oklahoma Press.