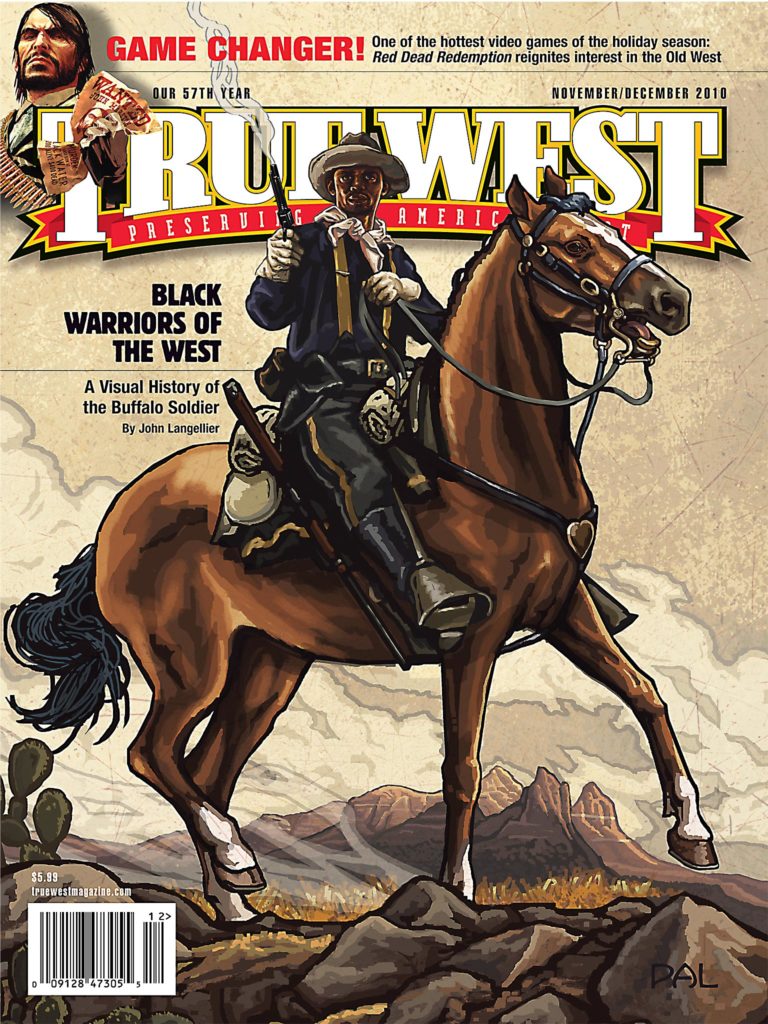

In the wake of the Civil War the American West offered perceived opportunities for nearly every element of society.

So it came to be that some blacks banded together in groups to cross the Mississippi River as “exodusters” bent on establishing a new society in the heartland of Kansas. Other blacks came as individuals to farm, establish businesses or engage in various livelihoods, including signing on as soldiers in the Regular Army.

In fact, a number of blacks, many of whom previously had been enslaved, joined Uncle Sam as a potential avenue to advancement, adventure and even escape from an old way of life, including the growing racial violence in the South as the promise of Reconstruction gave way to the Ku Klux Klan and Jim Crow.

Other individuals who had been displaced by the Civil War sought food, shelter, clothing and medical benefits. Then, too, veterans who had served in the Union forces, and others who were inspired by the record compiled during the fighting between North and South, saw continued merit in military service. Some men even looked ahead to a time after the expiration of their tour of duty and hoped they might parlay an honorable discharge into civilian employment with the government.

Perhaps pursuit of education motivated some knowledge-thirsty men who viewed formal learning as a road worth traveling, particularly after the Freedmen’s Bureau ceased to exist. One avenue for those who sought formal learning came from the assignment of chaplains to the black regiments. Clergymen in uniform were typically posted to a garrison, but in the black units, the chaplains were carried on the rolls of their respective regiments. In addition to their religious duties these military ministers were charged with providing education of their soldier flock.

Regardless of their motives for joining the military, these black warriors evolved into an important presence on the frontier. Throughout the latter part of the Victorian era they would gain a reputation as brave campaigners. They also typically boasted the lowest desertion rates and the highest re-enlistment rates of any regiments, far exceeding their white counterparts in these important areas. Fighting enemies in the field and prejudice at home, they compiled an impressive record, one that included photographic evidence capturing what it was like to live as a black man wearing Army blue during the last decades of the 19th century.

John Langellier received his PhD in history from Kansas State University. He is the author of dozens of publications focusing on military subjects, and also has served as a consultant to motion pictures and television.