The end of wars does not always mean the end of death and destruction. The Sultana tragedy proved that.

The end of wars does not always mean the end of death and destruction. The Sultana tragedy proved that.

In April 1865, Robert E. Lee had surrendered, President Abraham Lincoln had died from an assassin’s bullet and Union prisoners of war were returning from the terrible camps in the South.

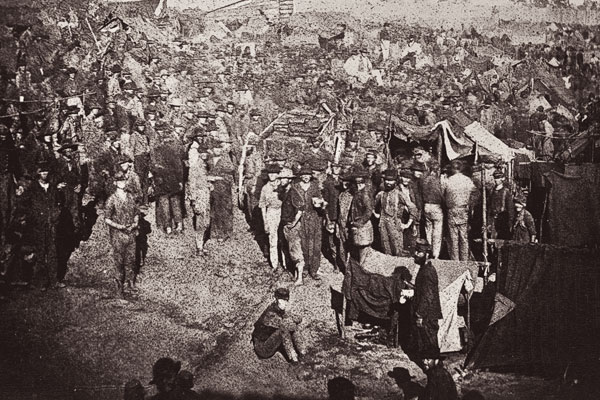

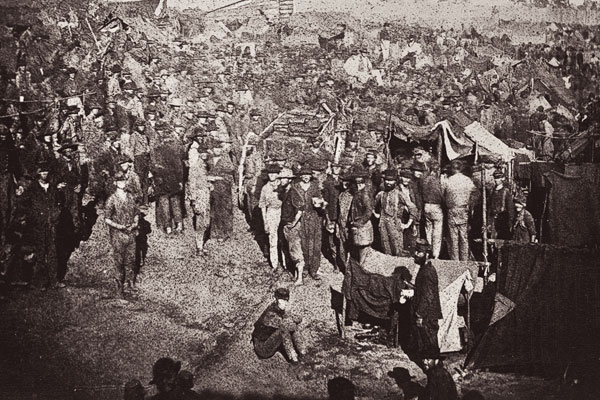

From Andersonville in Georgia, they were directed to the Sultana, a Mississippi river boat that could carry 376 passengers and crew. Private boat owners had discovered a lucrative business after the Civil War ended; the Army paid $5 per enlisted man and $10 per officer for the trip. Certain Union officers, including regional quartermaster Reuben Hatch, a man with a history of corruption, were reportedly getting kickbacks on the deal.

As many as 2,400 men were crammed onto the Sultana, more than six times its capacity. The exact number is unknown—officials stopped counting—but the ship was standing room only for men who were weakened by illness, injury and horrible incarceration.

Even worse, the boat’s boilers were in bad shape. Boilermaker R.G. Taylor placed a patch on one of them while the boat was docked in Vicksburg. He recommended that new boilers be installed before departure. He was ignored, and the Sultana began its voyage on April 24.

At about 2 a.m. on April 27, seven miles north of Memphis, Tennessee, the boilers exploded, ripping the boat apart and throwing men into the freezing river. Many died in the blast. Some died of burns. Others drowned or died from hypothermia. The first rescue boat got to the site an hour after the explosion.

The government reported as many as 1,547 men died in the tragedy, but since nobody knew how many had boarded, the death count was a guess. Even with this low count, this was the worst maritime disaster in our nation’s history. The famous Titanic shipwreck lost 1,513 lives.

Most Americans didn’t even hear about the tragic explosion. News-paper headlines focused on the death of Lincoln’s assassin, John Wilkes Booth, killed the day before.

The military brought charges against two officers, including Hatch, but neither was punished; both had political connections in Washington, D.C. that protected them. The Sultana tragedy was more or less forgotten for nearly 120 years.

In 1982, Memphis, Tennessee, attorney Jerry Potter organized an archaeological expedition to find the boat. His team hit paydirt when they found blackened wood from the deck under an Arkansas soybean field—the Mississippi River channel had moved about 300 yards between 1865 and 1982. The boat has yet to be dug up to rescue artifacts that could be showcased in a museum.

As of now, the only memorial to those who died in the Sultana tragedy is a small monument in a Knoxville church cemetery. That’s a tragedy unto itself.