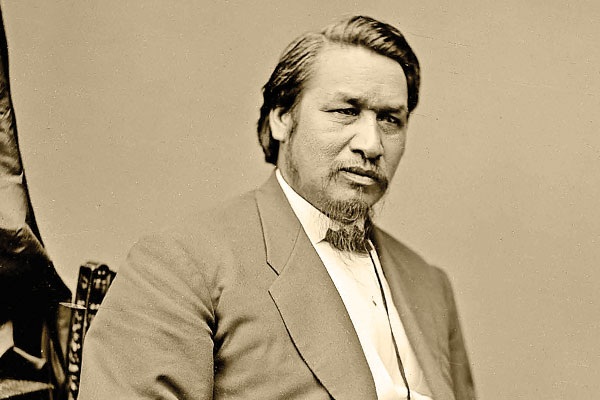

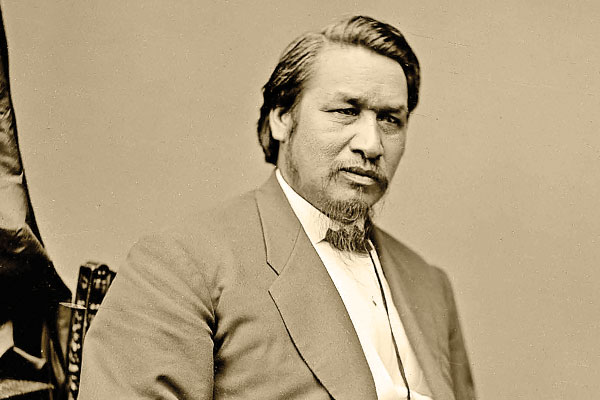

Seneca Indian Ely S. Parker was born Hasanoanda, which means “Leading Name,” in 1828 as his parents William and Elizabeth Parker attempted to return home in their buckboard to the Tonawanda Reservation, in Indian Falls, New York. His father was a Seneca chief, a veteran of the War of 1812, a Baptist minister, and a local miller; his mother a descendent of an Iroquois prophet.

Seneca Indian Ely S. Parker was born Hasanoanda, which means “Leading Name,” in 1828 as his parents William and Elizabeth Parker attempted to return home in their buckboard to the Tonawanda Reservation, in Indian Falls, New York. His father was a Seneca chief, a veteran of the War of 1812, a Baptist minister, and a local miller; his mother a descendent of an Iroquois prophet.

Ely’s life had been foretold to his parents, in a prophecy describing a distinguished warrior and peacemaker from their tribe.

At age 14, Ely first attended Yates Academy, and after two years transferred to the elite Cayuga Academy, where he learned self-confidence by stoically enduring racial hostility. Later, the Seneca gave him a new name, as he reached manhood: Donehogawa (“Keeper of the Western Door of the Iroquois Loghouse”). In 1851, he became great sachem of the Six Tribes–the head chief.

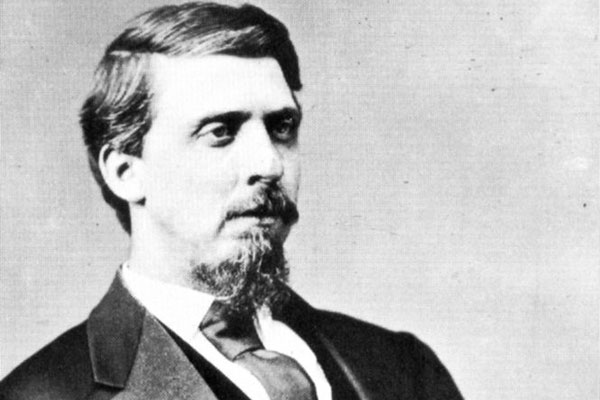

Despite the respect he earned from his tribe, Harvard University denied admission because he was an Indian; the New York Bar would not consider his application to practice law, saying he was not a citizen. He turned to engineering, earning a degree from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, and in 1857, met lifelong friend Ulysses S. Grant in Galena, Illinois, while working on two government projects.

Parker, who was told he could not fight for the Union because he was an Indian, turned to his friend Gen. Grant for help in May 1863, and Grant had him commissioned as a captain. Parker served in the Vicksburg campaign as an engineer, and later was attached to Grant’s command reaching the rank of lieutenant colonel before being brevetted as a brigadier general in the U.S. Volunteers on April 9, 1865.

As Grant’s adjutant, he wrote out the final articles of Confederate surrender in April 1865 at Appomattox. He later reported that General Robert E. Lee mistakenly believed that Parker was a black man and was surprised to see him serving in a prominent role. After learning his background, Lee said he was glad to see “one real American” there, to which Parker replied, “We are all Americans.”

After the war, Parker continued to serve on Grant’s staff. In 1869, President Grant appointed his friend the first American Indian to serve as commissioner of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. His two years as leader of the BIA was fraught with controversy and scandal as he attempted to enforce Grant’s peace policy in the West.

Parker, who never found success in business after the Wall Street crash of 1873, slowly sank into abject poverty and died on August 31, 1895. He was first buried near his home in Fairfield, Connecticut, but two years later, his remains were reinterred with those of tribal ancestors at Forest Lawn in Buffalo, New York.

Tom Augherton is an Arizona-based freelance writer. Do you know about an unsung character of the Old West whose story we should share here? Send the details to stuart@twmag.com, and be sure to include high-resolution historical photos

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy National Archives –

– Courtesy Library of Congress –