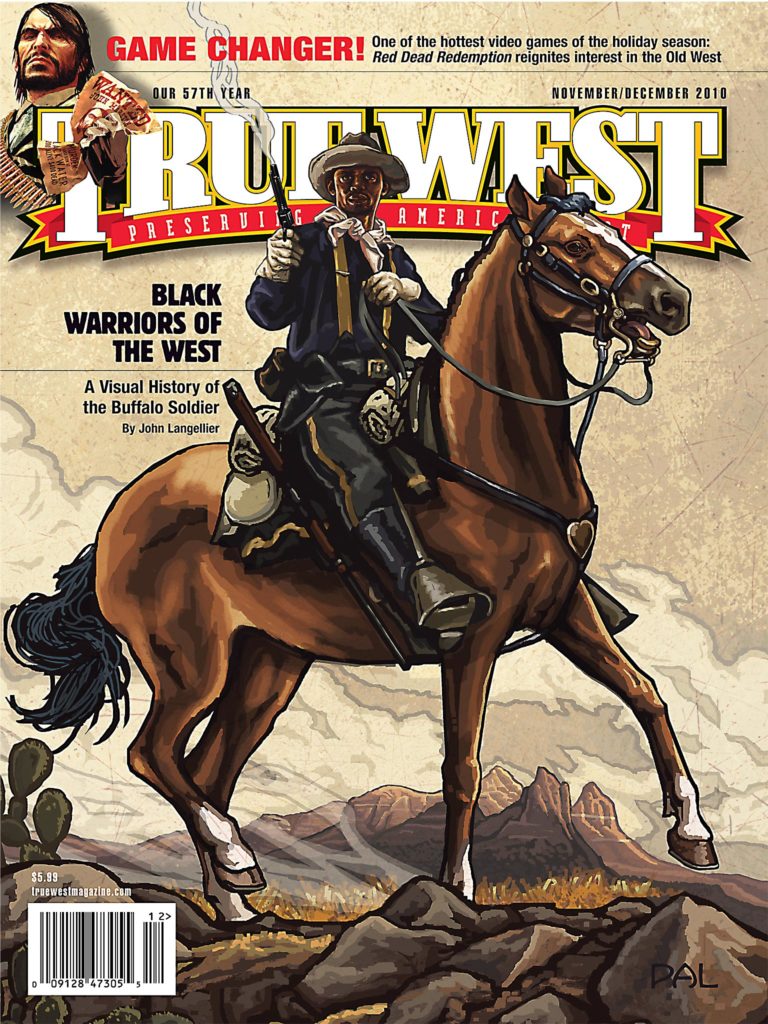

Since Red Dead Redemption was released in May 2010, many gamers have taken to calling the video game “Grand Theft Stagecoach,” a play on the name of one of the top-selling video games of all time, Grand Theft Auto.

Much like that game, your character starts off with nothing but his revolver and the clothes on his back. He builds up his reputation by accomplishing missions. For every mission you complete, you will unlock more of this movie-like Western world for your character to explore.

I worry about the Western. Like a lot of people who grew up in the Western wonderland of the 1950s-1960s, when Oaters dominated TV and movie screens, I’ve seen an ever-diminishing number of new productions. We’ve still got Clint Eastwood and Kevin Costner, Tom Selleck and Sam Elliott of course, but Unforgiven, Eastwood’s last Western, turns 18 this year, while Dances With Wolves is 20 years old. A kid could conceivably grow up having never seen a Western, or, at best, only a handful.

So I confess that when I sat down with 14-year-old high school freshman Matthew Rondberg and plugged Red Dead Redemption into his Xbox, I had no idea that I’d be the amateur in the room. I was the tenderfoot from the East, the guy they put up in the saddle who ends up 10 seconds later in the dirt with a sore behind.

Matthew was kind, and reasonably patient, as any decent kid would be with a hopeless geezoid. But once I got out of the way, he put on his headphones, joined a group of fellow kids through the multi-player feature and went savage, riding like a rodeo champ and killing everything in sight.

Red Dead Redemption is the biggest thing to hit the Western world since Unforgiven. The irony is, most of us who know Westerns are relatively unaware of it, or if we do know about it, are unlikely to possess the equipment and the skills needed to play it. Take-Two Interactive Software,

which publishes the game under its Rockstar label, just announced that it sold 6.9 million units since the game was launched on May 18, 2010. Considering that it retails on Amazon.com and other outlets at around $56 a unit, the company’s fiscal graphs must resemble a smiley-face emoticon.

Yet the sales aren’t the only reason why this game is important. The game shines because of the respect its creators give to the history, the landscape, the politics and the technology that existed in 1911. Red Dead Redemption offers an astonishingly complex narrative and a huge variety of diversions for the player as he moves through the story in pursuit of the central objective. Most important, it offers the player choices that color how the communities regard and react to him, which affect the events as they unfold. This is a game with cool guns, fast horses and karma.

Westerns fans will notice that the producers of the game didn’t draw only on Spaghetti Westerns, but also on movies that go back as far as 1948’s The Treasure of the Sierra Madre through both versions of 3:10 to Yuma and up to John Hillcoat’s Australian Western The Proposition. In fact, Hillcoat came aboard to direct a 30-minute film using elements of the game, which appeared first on channel Fox and then on Rockstar’s website.

But the game also takes into consideration the real West and what was happening throughout Texas and Mexico in 1911, moving the narrative in directions common to films such as 1966’s The Professionals and 1969’s The Wild Bunch.

The core story is about a man named John Marston, who is being forced to track down his former gang, one man at a time, by the government. This leads him across Texas to Mexico, where he meets and gets involved with a group of revolutionaries, before he returns to his original quest. The player is Marston, and how he behaves and the choices he makes in the course of the story are made by the player. Marston can be a vicious killer, wanted by the law, or he can play it straight and pass a “Howdy” at the local sheriff on his morning stroll.

In the parlance of the game, how the character behaves is called “honor.” Fame and positive honor can be achieved, for example, by saving a civilian or resisting the impulse to kill a bad guy. Negative honor, something like what my young friend Matthew was by nature inclined toward, comes from killing and slashing everything in sight. Trees, houses, horses—it doesn’t matter. If it moves, or even if it doesn’t, kill it.

As for myself, I was having too much trouble just figuring out how to make the character walk and chew gum to make any significant moral choices. This is a game rated to take 30 hours to work through. When the game requires learning a complete skill set just to keep your horse from flying off a cliff or running headlong into the rocks, a novice player could certainly stretch those 30 hours into the distant ends of his or her sunset years.

Anybody who needs a second opinion on his or her game-playing ineptitude can thank the authors for scripting in a considerable variety of snarky remarks that other characters will lob in your direction without hesitation when you’re not playing up to snuff. What’s said is no less than you deserve, and humiliation can be character building, even if it comes from the mouths of fictitious characters on the TV that you bought and paid for.

Once you’ve moved into the flow, the real joy of the game is its many diversions. Marston can sidestep the story by: joining a poker game, helping the local law enforcement in a midnight firefight, watching a hanging, meeting strangers, hunting for pelts or dinner, or even defending himself against animal attacks.

Animals, in fact, are a perfect example of what kind of thinking went into the details of the game. “The vast world of Red Dead Redemption is home to a complex ecosystem of over 30 different species of animal, ranging from domestic farm animals to deadly predators,” states a Rockstar spokesperson. “Each separate territory—from the frontier ranges of New Austin, down into the parched and dusty border territories of Nuevo Paraiso, Mexico, and up into the greener, mountainous areas of West Elizabeth—is home to its own distinct species and breeds of animal…dogs will chase wagons or bark at potential enemies, barnyard animals will herd together or take fright at loud noises, large birds will scavenge from corpses, and predators, like bears or wolves, will put on aggressive threat displays and fearlessly attack humans.”

I can’t say for a fact whether any Gila monsters lurk under rocks in the game, but if not, they might be added at some point in several upgrade packs that are available now or in the coming months. While a marginal supernatural element is already at work in the original, one of the upgrades introduces a complete zombie storyline. How Marston is able to kill the already dead is yet to revealed, but it will be fun to see a few bad hombres climbing out of boot hill.

Past the plot, the history, the flexibility and the detail that went into Red Dead Redemption, the world of the game is strikingly beautiful. As more than one critic has commented, the sunsets and vistas are gorgeous.

Red Dead Redemption may not be the entire future of the Western, but the video game industry is shaping up to be a big part of the Western’s future. Western history and movie aficionados who wish more young’uns would hop on that creaky stagecoach and take a ride should be more than happy that this game is such a fantastic success among people who have few, if any, Westerns in their past. As the saying goes, “Every generation gets precisely the Western it needs.” For this generation, Red Dead Redemption is that Western, and it’s a damn good one.

Henry Cabot Beck is the Film Editor for True West, writes about pop culture in general for other publications and is a member of the Phoenix Film Critics Society.