– All Images Courtesy Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument Archives, NPS.gov Unless Otherwise Noted –

The 1876 Battle of the Little Bighorn has played a major role in the legends that have shaped our nation’s history. That controversial clash of cultures includes the stories of those present on that bloody Sunday in Montana Territory, first and foremost among them Lt. Colonel George Armstrong Custer. This, however, is a tale about a less-known participant—and what he did or did not witness at Custer’s Last Stand.

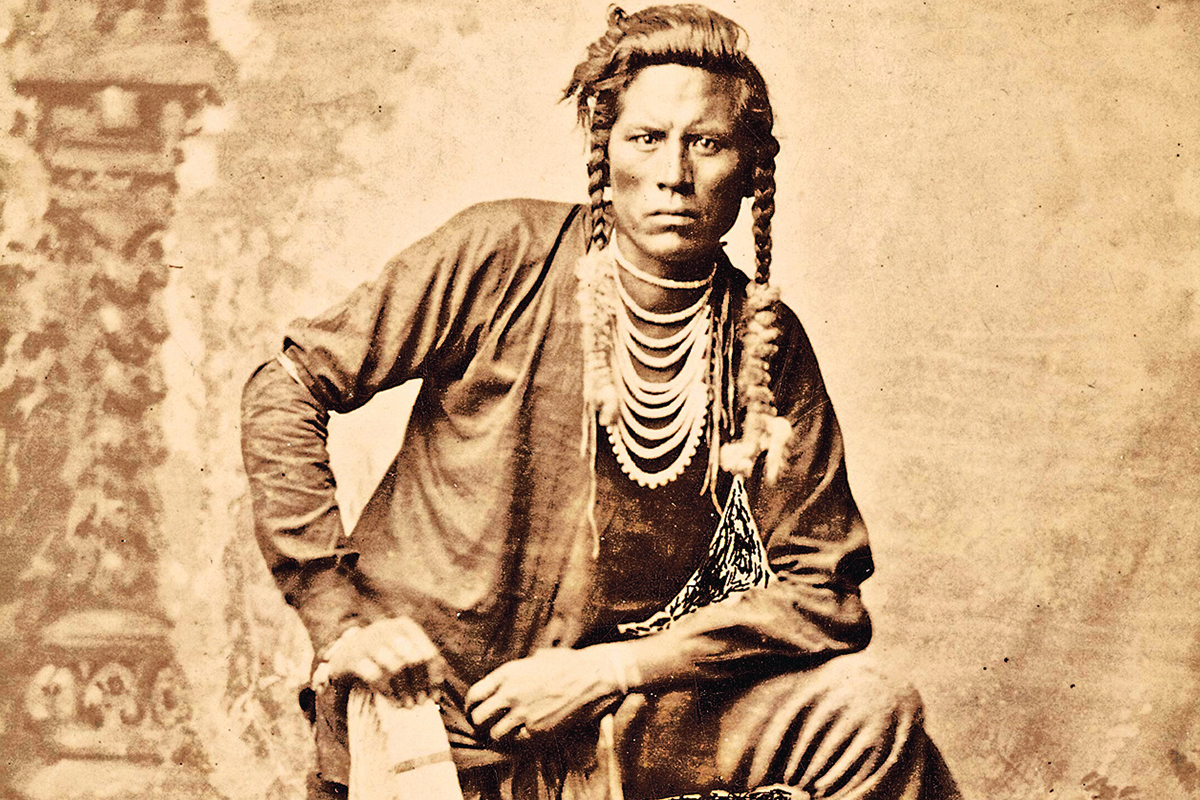

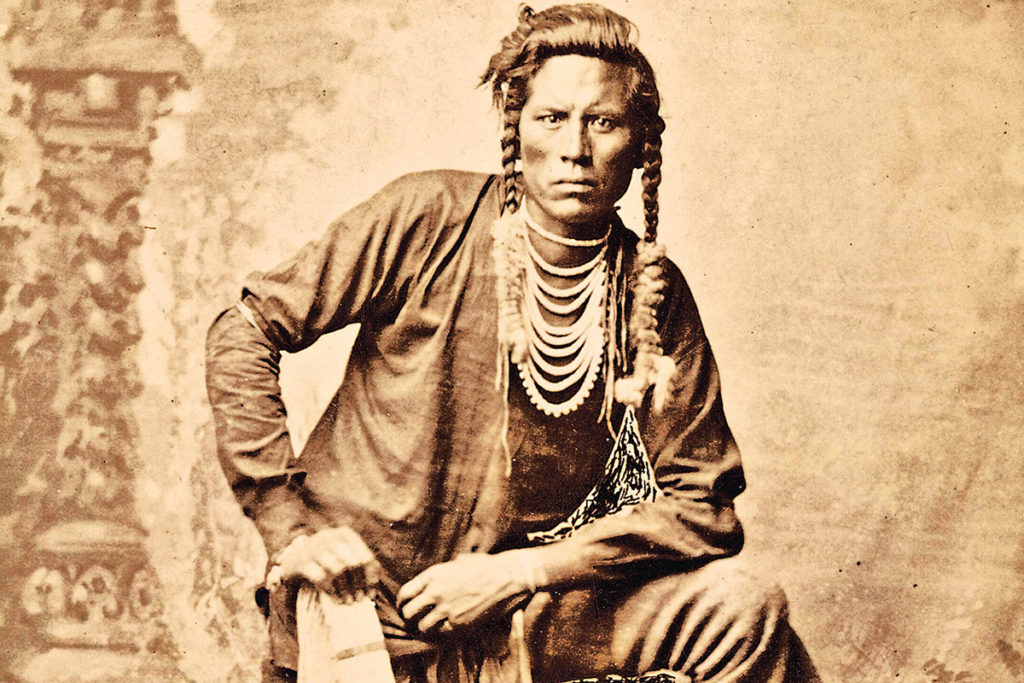

Six Crow Indian scouts and the guide/interpreter “Mitch” Boyer were assigned to Custer and the 7th U.S. Cavalry because they knew the country well. They also had a stake in defeating their tribal enemies, the Lakota Sioux. On the morning of June 25, 1876, Boyer and the scouts spotted their target in the Little Bighorn Valley, as evidenced by the smoke of the Lakota campfires and evidence of an enormous horse herd. After Custer ordered Maj. Marcus A. Reno’s battalion forward when the Indian encampment along the Little Bighorn appeared to be in flight, Boyer and four of the Crow scouts (Curly, Goes Ahead, Hairy Moccasin and White Man Runs Him) rode with the five cavalry companies under the colonel’s immediate command toward what became known as Custer’s battlefield. Boyer would die with Custer. The four scouts would survive the battle. [See “Custer, Crows and Curtis,” True West, July 2019.]

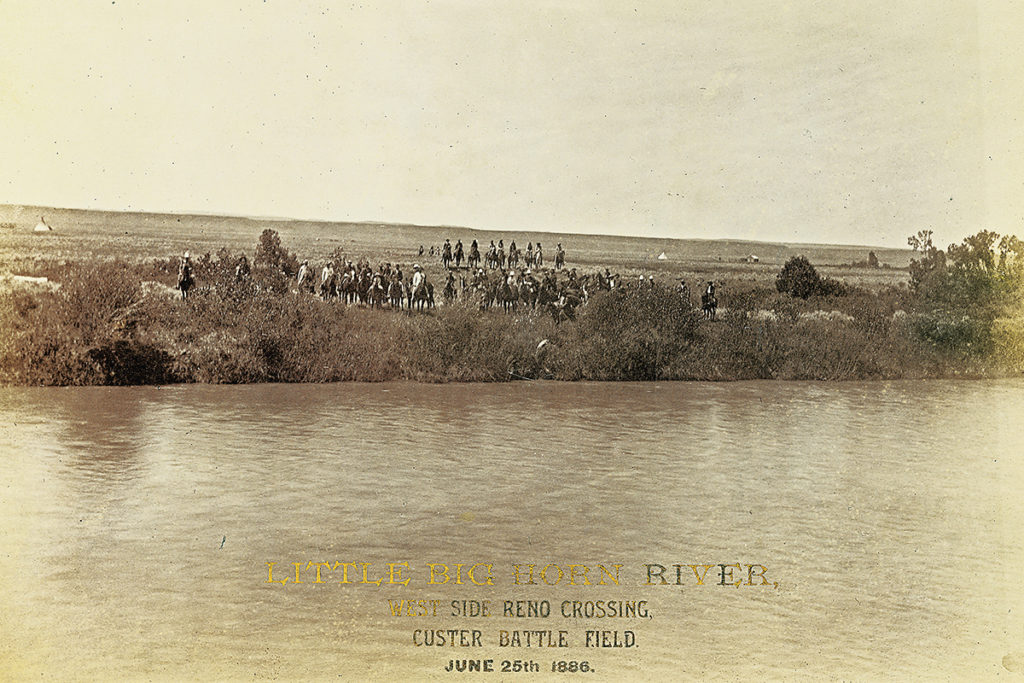

At this point the scouts’ exact movements are unclear, but we know that before Custer’s last fight Curly (or Curley) separated from the other Crows, that none of them witnessed the entire battle (if they witnessed anything all), and that all four left the Little Bighorn Valley that day. On June 27, Curly appeared at the steamboat Far West that was moored at the mouth of the river. Accounts differ as to the details provided by the dejected scout, but he gave the clear impression that the battle had been a disaster. The three other scouts had already communicated a similar message, when they encountered the Crow scouts with Col. John Gibbon’s Montana Column the day before.

Curly soon became known as a witness if not “the only survivor” of Custer’s last battle. “His story,” the Bismarck Weekly Tribune reported on July 12, 1876, “though fully not understood…proved too true in all its details.” Others inferred that he had participated in the fight, including Major Reno, who reported that “an Indian scout” with Custer related “what he saw of the battle.” In 1881, Curly informed Lt. Charles F. Roe of the 2nd Cavalry that Custer had been repulsed attempting to ford the Little Bighorn to attack the village. Sioux and Cheyenne warriors “rode right up to the command firing all the time, plenty of them. The troops fought on the ridge, firing into the Indians as they came across the river and up the slopes.” Later, Curly claimed, he had gone to a distant ridge but “saw there was no one moving, no one firing and all the troops appeared to be killed.”

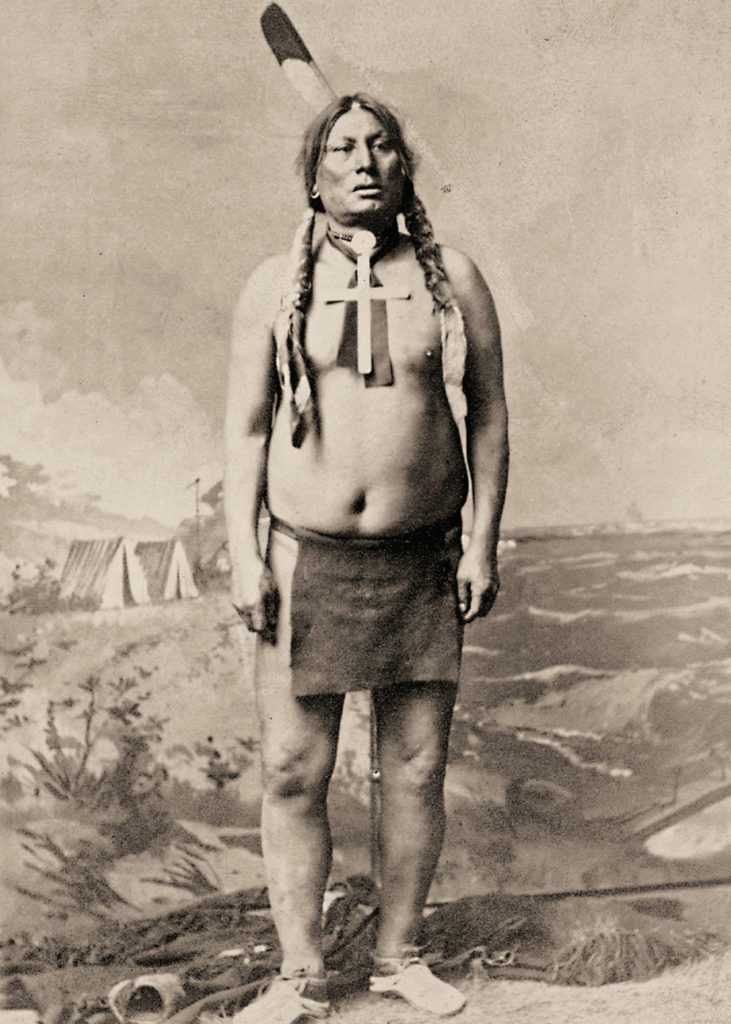

The scout’s status as a survivor (or witness) of Custer’s Last Stand seemed unchallenged (at least to the public) until he and the Lakota war leader Gall attended the tenth anniversary observance of Little Bighorn at the battlefield in 1886. Gall claimed that Curly could not have known anything about Custer’s last battle. “He ran away too soon in the fight,” he asserted, as he turned his back on Curly.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

Although historians have questioned Gall’s description of Custer’s route to the battlefield, he provided a credible, if not complete, account of the battle on that occasion. Be that as it may, he and other Lakota warriors could not have known or recognized Curly in the confusion, dust and smoke of battle. The scout’s reputation seemed intact. But doubts as to his story had been raised before Gall’s comments appeared in the press.

Within days of the battle Gibbon’s chief of scouts, Lt. James H. Bradley, interviewed Curly at length. Already credited as the battle’s “sole survivor,” the scout repeatedly denied that he had been in the fight. “He told us,” interpreter Thomas Le Forge recalled, “that when the engagement opened he was behind, with the other Crows. He hurried away to a distance of about a mile…and looked for a brief time upon the conflict.” The scout was adamant. “I did nothing wonderful. I was not there.” Further doubts were raised when Curly returned to the battlefield in 1877 as Col. Michael V. Sheridan exhumed the bodies of Custer and other officers killed at the Little Bighorn for reburial. “Curly showed me…the place at which he deserted Custer,” Sheridan reported, “and I soon became fully convinced that he had run away before the fight really began, and that the greater portion of his tale was untrustworthy.”

Years later, the three other Crow scouts (who also had left Custer just before or soon after the fight began) denied his presence. “Curley had left us at Weir Peaks,” Hairy Moccasin, for one, claimed, “and cleared out of the country.” Goes Ahead alleged that Curly “disappeared” more than a mile even farther to the south, near where Reno’s command would be besieged. Attesting to his disappearance was Custe r’s orderly, Pvt. John Burkman, detailed to the pack train that followed the command along Reno Creek to the Little Bighorn. He informed battle researcher Walter M. Camp that he saw Curly and several of the Arikara scouts heading east about two miles from the river, driving Sioux horses and “running away from the fight.” Other battle survivors confirmed this hurried departure of the scouts, who warned of “Heap Sioux!”

If Burkman was correct, Curly could not have been present at Custer’s last battle, based on the time and distance he had travelled to the pack train. In 1908, for example, he confessed to the Crow Indian agent that he “did not get into the fight, but saw it from a ridge north of the field.” However, he could not have seen anything from the ridges where he claimed to have “looked for a brief time upon the conflict,” as he told Bradley and Le Forge. “I have done sight tests from the area where he supposedly watched the battle,” Seasonal Battlefield Ranger Michael N. Donahue has informed us, “and you can see nothing, especially if there was any smoke or dust (which there was).”

For the sake of history this “sole survivor’s” tale must, therefore, be put to rest!

Postscript

Curly often related his alleged experiences at Little Bighorn. Between 1908 and 1913, for example, Walter M. Camp interviewed him on four known occasions (including at least one visit to the battlefield) assisted by Tom Le Forge and other interpreters. His accounts became not only more detailed but also more embellished. They included the claim that he had been present with Custer’s command after it retreated from the river and at Boyer’s urging escaped from Calhoun Hill at the southern end of the battlefield as they were being surrounded.

Curly also threw the other three Crow scouts under the bus. He told Camp that before Custer went into action, they “turned tail and put back up the river following our trail along the bluffs.” After they had left, he and Boyer “joined Custer…as he was advancing toward the village.” No wonder bad blood toward Curly was apparent when Maj. Gen. Hugh Scott and Col. Tim McCoy interviewed the four scouts on-site in 1919. “We did not see Curly,” White Man Runs Him argued, when “Boyer told us to go back.” Their antipathy toward him was clear. “The three Crows against Curly hang together,” Scott told battle survivor Luther R. Hare. “I believe Curley [sic] left long before he says he did.” (The story of three scouts is a tale for another time.)

Yet Curly, by then, had told a more credible version of his Little Bighorn experience. As Custer reached the river, Curly said that Boyer informed the scouts he was joining Custer “and for the rest of us to go back to the pack outfit.” Retracing his steps, he turned east up Reno Creek and “met the pack train. The outfit went on through and that was the last I saw of them.” He followed a circuitous route to the mouth of the Little Bighorn, where he encountered the Far West two days later.

C. Lee Noyes resides in Morrisonville, New York, with his wife, Michele, whom he credits with reviving and sustaining his longtime passion for the 1876 Battle

of the Little Bighorn.

Editor’s Note:

C. Lee Noyes is this month’s guest “Build Your Western Library” columnist in “Western Books.” Go to page 43 to read about his favorite books on the archaeological history of Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument.